Writer Justin Zhuang Documents Design, and Design in Culture

In Singapore, there are just a handful of people known for writing dedicatedly about design. DesignSingapore Scholar Justin Zhuang is one of them. His pathway to thinking critically about design developed naturally as a by-product of his curiosity about history and culture. Now playing his own part in documenting the history of Singapore’s design, he is helping us understand our designed present and future.

Article by Narelle Yabuka.

Design-focused publishing has peaked numerous times over the last two decades – in print magazines, then on websites, on social media, and now in the podcasting realm (with books remaining a faithful constant). With the rise of each format, it’s been possible to find productive and counter-productive examples of how design is documented and communicated.

We’ve been able to enjoy examples of critical engagement with the context and meaning of what and how we design. On the flip side, there has also been content that glosses over the rigorous research and thinking that goes on behind the process of design.

“I was never interested in seeing design as a lifestyle,” says writer Justin Zhuang, positioning himself squarely in the former camp. He adds, “My internal mantra was always design as life. My interest is design in a larger context – as something that has the potential to frame our understanding of things.” It is an insightful perspective stemming from an interest in history and culture, and a sign of strong innate interest given that Zhuang – a Partner at editorial studio In Plain Words – never studied design.

Since completing undergraduate studies in journalism at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in 2009, he has allowed his journalistic curiosity to guide him toward design’s presence in our material culture. He has written about designs that originate from both design professionals and the creative solutions people find to everyday problems – especially favouring the latter.

With the support of a DesignSingapore (Dsg) Scholarship, his fascination took him all the way to New York City in 2013, where he embarked on master’s studies in design criticism at the School of Visual Arts. He is the only Dsg Scholar to have opted to study in this field.

Today he is one of a small number of writers in Singapore known for dedicating their attention to design. He plays a crucial role in documenting Singapore’s design within the framework of the nation’s culture and history – vital work for enhancing design literacy. Unsurprisingly, his portfolio includes many projects supported or initiated by Dsg, which sit alongside an impressive array of other books, articles, and editorial efforts.

For me, design has a much wider definition than what is produced by the design industry. Design is anything that has been shaped by some kind of intention.

— Justin Zhuang

Reframing how we think about design

“I’ve always been quite irked when people use the term ‘designer chair’ – as if a chair by itself is not designed,” says Zhuang. He continues, “I think that in Singapore, many people see design as something that’s an add on – a value add. There’s a perception that you need a certain income and status to own a so-called designer chair or designer clothes, and that if you own these things, then you’re slightly superficial. This is why in a lot of the projects I do, I’m trying to point out that design is everywhere. It’s part of anything that has been constructed.”

Zhuang’s own introduction to design came via his creative input to the layout of The Nanyang Chronicle, an NTU campus newspaper, and the discovery through trial and error of graphic design’s potential to influence perception. “With graphic design, depending on the way you lay out a page and the kinds of typefaces you use, you can communicate the same message differently. That’s how I first noticed design,” he explains.

A six-month exchange at the University of Maryland in the USA provided the next nudge toward the world of design. Zhuang noticed the way international graphic and typography design magazines such as Eye and Baseline examined historical episodes via elements such as the dominant typeface designs of the times. “It made me realise that you can use design to look at history and culture, which I was always interested in. So I thought, since I’ve studied journalism, I could aim to start doing pieces like that,” he recalls.

A final-year article about the typefaces he encountered in Singapore and their possible links to national identity gave him his first big break when it was published in The Singapore Architect, which was then headed by Kelley Cheng. As he ventured into this exploration, Zhuang also had the privilege of interviewing Chris Lee, founder of award-winning creative agency Asylum. His graduation project was a voyage into the ways people were “reclaiming land” and using it informally in their own ways. For example, he found a street barber who set up shop in a laneway behind Boon Tat Street, migrant workers who made use of unused roadsides and fields as spaces for socialising and cricket games, and public housing residents who nurtured their own plants in common garden areas within housing estates – all creative acts embedded in daily life and culture, by Zhuang’s estimation.

Later, this exploration of the intersection between culture, history, and design for the built environment was also evident in Zhuang’s work on the old mosaic playgrounds of Singapore that were designed by Khor Ean Ghee. Released near the height of nostalgia-fever during Singapore’s golden jubilee year in 2015, his writings on Khor’s iconic playground designs were compiled into an e-book titled Mosaic Memories for the Singapore Memory Project. Thereafter, Zhuang went on to work on other associated heritage projects that examined the role of design within the cultural milieu.

For him, the confluence of city, culture, and design was a mesmerising combination, and he grew to realise that writing about design while being an outsider to the design industry affords him a unique perspective. Free from industry norms and expectations, he is able to take a far broader view of what constitutes valuable design dialogue.

Intrigue beyond the obvious

“I’ve always liked design stories that are not obvious because the design is so ubiquitous,” says Zhuang. A perfect example is the humble plastic kopitiam chair found all over Singapore – which became the subject of an article published in now-defunct Dutch magazine Works that Work. The familiar local version is just one of many derivatives (found globally) of Joe Colombo’s Universale chair, which was first produced in Italy by Kartell in 1965.

Zhuang traced the kopitiam version to the Mah Sing Plastics factory in Selangor, Malaysia, where it has been produced since 1987. Unlike its cousins elsewhere, Mah Sing’s version has rows of rain-ready drainage slots on both the seat and the spine and, as Zhuang describes, an “Asian-friendly size”.

Objects and graphics that people use every day may or may not be designed by a professional designer, but they do serve the function of design. They communicate or function in a particular way. It’s always intriguing to find out the anonymous names behind them.

— Justin Zhuang

Zhuang investigated another side of anonymous design via pirated works as a conclusion to his master’s studies in New York. While knock-offs are typically looked upon with disdain for their breach of intellectual property and their inferior quality, he focused on the participatory potential offered by 3D printing.

He stumbled upon a community, the Bronies, who were 3D printing their own versions of My Little Pony toys. “It was very interesting for me to see that Hasbro, the toy manufacturer, didn’t reject it and call it a form of piracy. Hasbro embraced it and gave the Bronies a platform to sell, taking a cut. It was a win-win, and to me, it was a very interesting model. It encouraged fan participation – and the fans made interesting stuff,” he explains.

Ultimately, Zhuang questioned: If 3D printing can produce a fake that in some ways improves upon the original design, is denouncing piracy always the way to go? But he was also fascinated by how non-designers were producing objects with value. “The study in New York gave me more confidence that the things that I was really interested in looking at could also be considered part of design,” he reflects.

Creativity beyond the profession

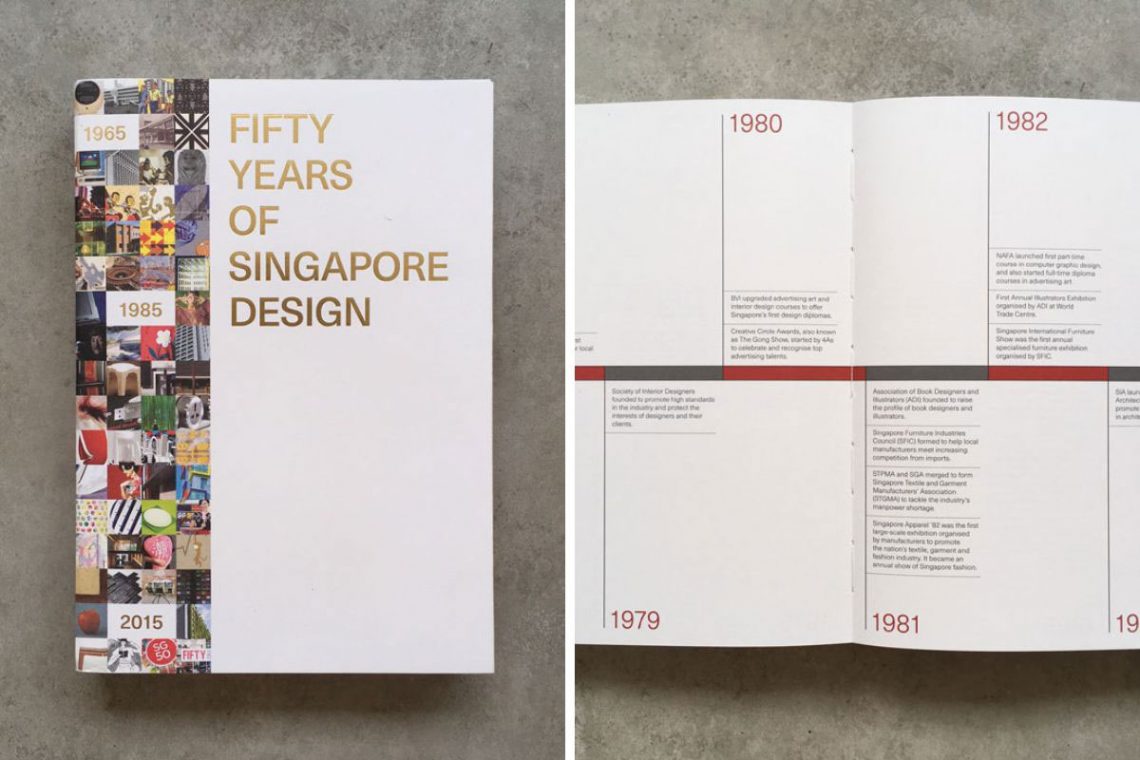

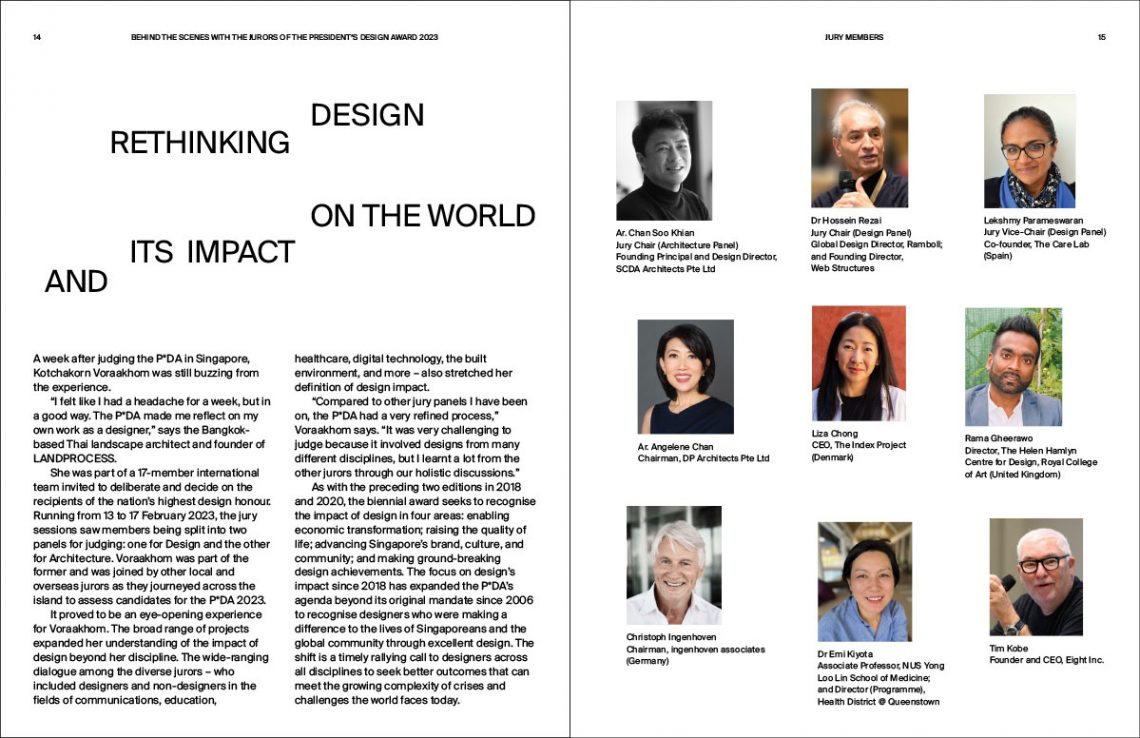

Back home, after working on various Dsg projects (such as the book Fifty Years of Singapore Design, writing for the President*s Design Award [P*DA] publication and website, and showcasing the Singapore Design Archives at the National Design Centre), he followed his intuition about the creativity that dwells beyond the design industry with a Dsg-supported book that was released during Singapore Design Week (SDW) 2019.

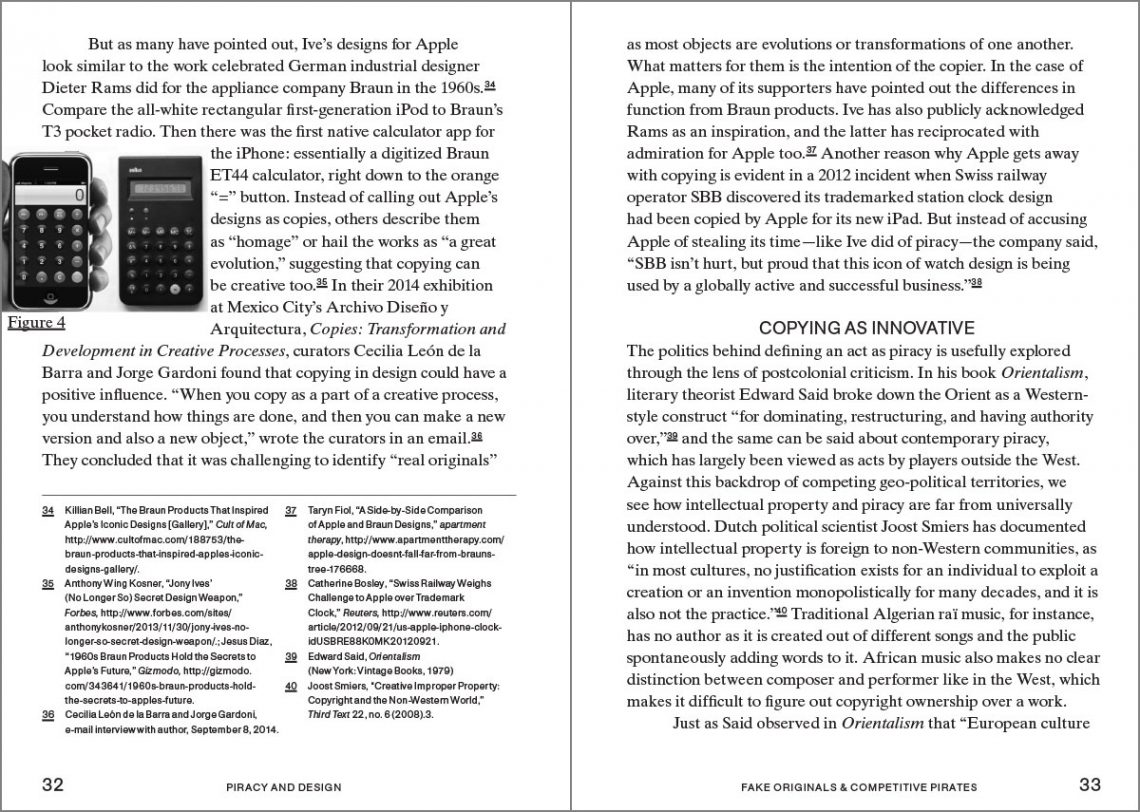

A collaborative effort between Zhuang, his partner in work and life Sheere Ng (Partner at their editorial agency In Plain Words), and graphic design agency Modular Unit, the book By Design: Singapore examines how design can be more than a consumer product or invention. It is also, as suggested by the ten essays of the book from various contributors, an action that each of us can take – whether the purpose is to help us overcome a challenge, or to make an impact on the world.

Hence, By Design: Singapore features an array of creativity ranging from a prosthetic beak for a hornbill, to data centres with improved energy efficiency, to the tools that local hawkers have fashioned to prepare traditional delicacies. On the cover of the book is a chair (discovered and photographed by Don Wong) that has been modified by its owner to provide extra support to the sitter, resulting in a fascinating collage and enhanced functionality.

Zhuang’s interest in uncovering such everyday design stories led him to later publish a book titled Aesthetics Aside: Observations on Design in the Everyday (2022), which comprises a collection of 30 essays he has written for magazines over his decade-long career.

I like to see how people interact with design. When designs are used in ways they are not intended to be, the outcomes can actually be quite clever.

— Justin Zhuang

With the scarcity of design-focused writers in Singapore, Zhuang has not been short of opportunities to provide editorial input to publications focused solely on professional design, either. His other efforts with Dsg have included copyediting the Council’s UNESCO Creative City of Design Monitoring Report and Design Education Review Committee Report in 2019; and writing for the Design Education Advisory Committee’s Term 1 Report and newsletter, the SDW 2022 EMERGE @ FIND catalogue, the SDW 2023 exhibition Playground of Possibilities, and articles for this very website – including a number in this anniversary series.

Most recently, he and his studio partner Ng undertook research and writing for the Hawker Colours project by designer Hans Tan, which has evolved from a website that was used to survey the public into a printed book. The website was supported by Dsg through the Good Design Research programme. The project studied the importance of coloured melamine bowls and plates to the heritage narrative of Singapore’s hawker food and culture, and the associations we make between particular melamine colours and dishes. “It’s the surprise of the everyday that always fascinates me,” he says.

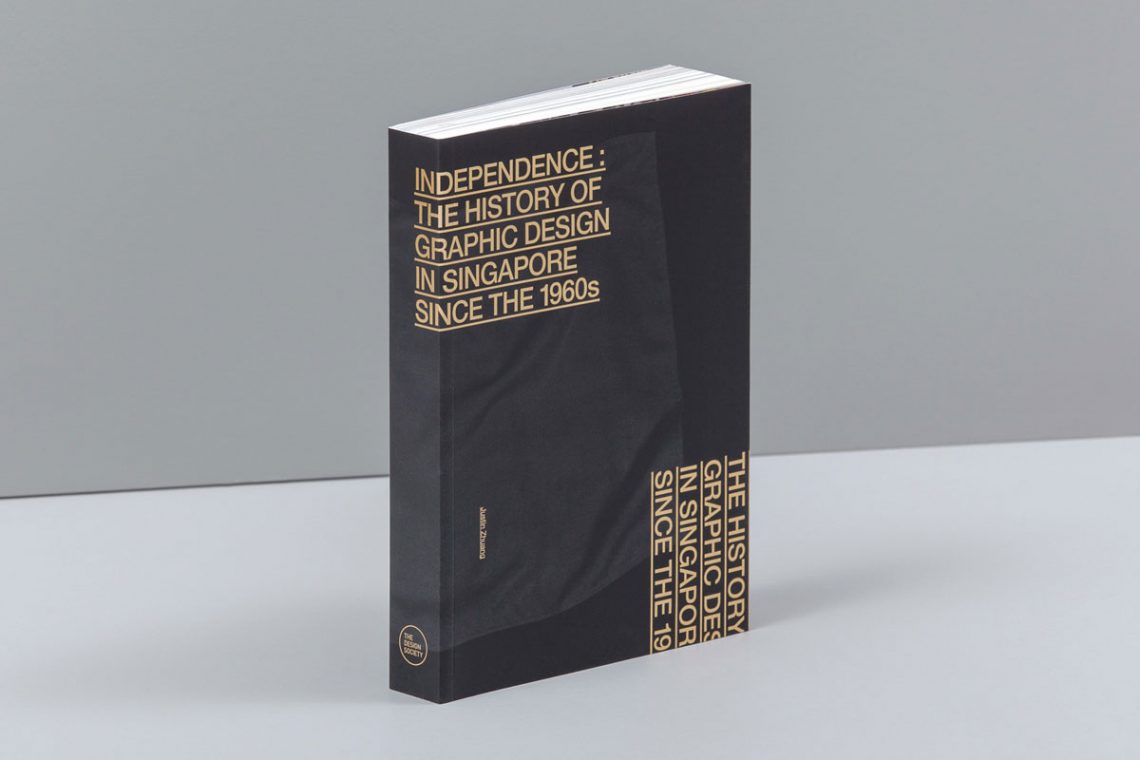

His other work has included articles for the local and international press, as well as an array of books about design and designers. The earliest of these was Independence: The history of graphic design in Singapore since the 1960s, published by The Design Society in 2012 and representative of one of Zhuang’s earliest (of many) collaborations with graphic designer Hanson Ho of H55. Zhuang’s more recent books include two monographs (on designers PHUNK and architect Mok Wei Wei) published by Thames and Hudson, for whom he is a Southeast Asia Editorial Consultant.

The value of documenting design

In December 2023, alongside co-authors Chang Jiat-Hwee and Darren Soh, Zhuang was honoured with a Colvin Prize by The Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain for the book Everyday Modernism: Architecture and Society in Singapore (published in 2022 by Ridge Books, an imprint of NUS Press).

The annual prize honours an outstanding work of reference that is of use and value to architectural historians and the discipline of architectural history. It is certainly a satisfying reminder of the value of recording and ruminating on design in Singapore.

“I think it’s important to document design, for sure,” says Zhuang. He continues, “Even back when I was working on the book Independence, I relied on reports and newspaper articles to retrace the history of design in Singapore. By doing that, I could also better understand Dsg’s context and how it was formed to address a particular context – the rise of the creative economy.”

“Human beings all have very short memories,” he suggests. “As someone who’s looked at a lot of design history, my starting point for writing is always that somebody must have done this before. But it doesn’t mean I cannot do it again. How can I build upon it now? Documentation of design helps us appreciate how we can do some of the things that we’re able to do today.”

History is very useful for understanding where we are, but also the possible routes into the future.

— Justin Zhuang

Read our unfolding series of stories on creative discovery and making life in Singapore ‘Better by Design’.