STUCK Design Wants to Score Victories for Humanity

How can life be lived better? How can we be better at thinking creatively? How can creative processes be better? Evolving from traditional industrial design to the realms of design research, education, and creative advocacy, STUCK Design consistently looks for ways to make a positive difference – always with a human lens.

Article by Narelle Yabuka.

There are plenty of sleek and smart products showcased on the STUCK Design website – just as one would expect of a creative studio that has its roots in industrial design. They range from the locally owned Morning capsule coffee machine and its companion app for customising one’s brew; to the Arc Touch Mouse for Microsoft that can snap between flat and curved configurations for both portability and ergonomics; to a series of respirator masks with detachable ventilators that received the President*s Design Award (P*DA) ‘Design of the Year’ accolade in 2015.

Among the product, user interface, and branding projects, however, are several examples of design research that represent the tip of an iceberg – an array of work and activity beyond traditional industrial design practice that the studio has increasingly embraced over the years. You’ll also see designs for COVID-response products that were offered license-free during the pandemic.

The thread that ties it all together is a determination to make a difference in people’s lives – whether through researching the needs of communities in relation to place, space, and services; building creative confidence in school children; or responding to health needs. From the point of view of STUCK Design’s Co-founders Lee Tze Ming, Yong Jieyu, and Donn Koh, design is a confluence of opportunities to score victories for humanity.

An evolving practice

The trio, who studied industrial design at the National University of Singapore (NUS) in the early 2000s, founded STUCK Design in 2010 after working together (and with others) as freelance designers for Dell – developing a design language for its Inspiron series of laptops and desktops.

“All of us came back to Singapore around the same time after working or studying in different places after NUS,” explains Koh. This included Yong’s master’s study in conceptual design at the Design Academy Eindhoven from 2006 to 2008, which he undertook with the support of a DesignSingapore Scholarship. “When I received the project request from Dell, I thought it would be more fun to explore with others. That’s how it all began,” says Koh.

The name STUCK refers to the positive and negative sides of the creative process. “There’s something good about being stuck on a problem,” says Lee. “That’s when you come up with sticky ideas,” he adds. Currently there are around 20 people exploring sticky ideas in the STUCK Design team, servicing local and international clients. While those clients come from a broad array of contexts, many of them have “some relationship with tech, some relationship with healthcare, or some social element,” Lee explains.

The last of those categories points to the most pronounced deviation from traditional industrial design practice, and reveals how significant the field of design research has become in the STUCK Design repertoire. “Research has always been part of product development.” says Lee. “But our work in redesigning systems, or approaches to spaces, or guidelines takes this further.”

Our mantra is to make things people love. Beyond aesthetics, we are looking at what drives things to be well used, and for people to form an emotional connection with them. This extends from products to interfaces to experiences. Spaces are a manifestation of that.

— Lee Tze Ming

The expanding universe of design research

For STUCK Design, design research work – beyond the realm of the product – really took off with a project commissioned by the DesignSingapore Council (Dsg) in 2016. At that time, Yong recalls, Dsg was pushing for human-focused design thinking to have a voice in urban planning considerations. STUCK Design was engaged to produce a ‘design ethnographic study’ that would bolster understanding of how people might live, work, and play in the upcoming Punggol Digital District, a hub not only for companies working in the digital sector, but also a university campus.

STUCK Design produced a set of research insights about the work, lifestyle, and spatial preferences of people from the digital sector, as well as perceptions about Punggol (including positive sentiments about the area’s green character) that were presented for consideration to a multi-stakeholder group leading the project.

Since then, the studio has undertaken research for projects ranging from preschools to hospitals to nursing homes. “More and more architecture projects are now taking a human-centred starting point,” says Yong. “We help with the design thinking process, talking to stakeholders on the ground before the design of the space or building begins. We help the client to develop a more human-centred design brief for the architects to execute.”

Increasingly, he adds, STUCK Design is also working hand-in-hand with architects to translate the brief in the early part of the design process. This is in perfect alignment with the trio’s wish to see upstream research make a tangible impact.

When we started STUCK Design, we never imagined we’d be working with the built environment sector, but now there’s a nursing home nearing completion. It’s been quite surprising for us, but it shows how design is changing. The lens is more human.

— Donn Koh

Making life better for people

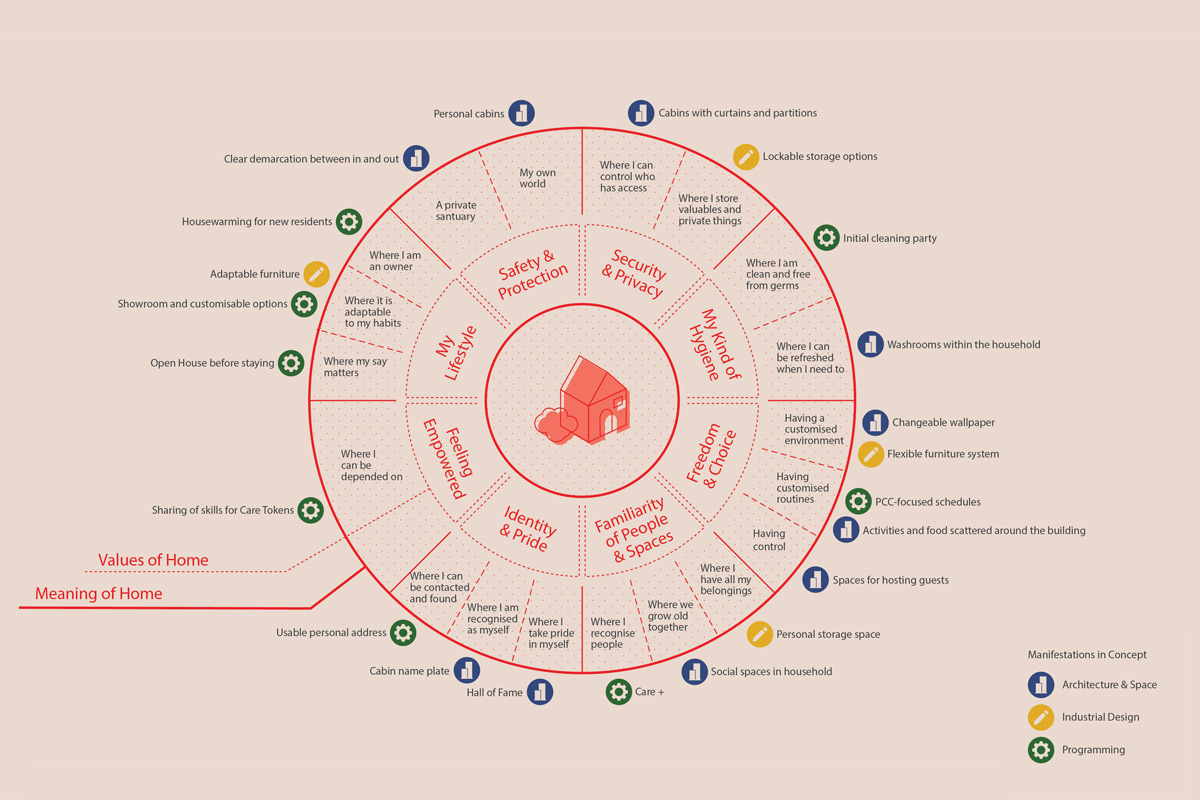

Questions of dignity and personal agency for nursing home residents were top of mind for STUCK Design during a project with architecture and design studio FARM for a new nursing home at West Coast Link, developed by the Ministry of Health (MOH) Holdings. The brief called for a new typology of care, and STUCK Design’s research insights proposed a variety of strategies for making the institution more home like and person centred.

“A classic example is that typically, in a nursing home, you don’t get to choose what time you shower. Imagine that you have a fall, and then you are uprooted from your life at home and placed in a nursing home. Suddenly, you can only shower in the morning. The change can be abrupt and drastic. So one of the insights was simply about giving choices,” explains Yong. He continues, “I found that project to be very meaningful because the agency was committed and we could directly see the impact our research could make.”

Right from the start, the architects shadowed us during our research work. They even conducted interviews with us. Then we paired out researchers and designers with them in a co-creation session. It allowed the translation of research to design to be done with first-hand knowledge. It made a huge difference in how the design was realised in the end.

— Yong Jieyu

Yong took his concern for quality of life among seniors further with a design research project supported by Dsg’s Good Design Research (GDR) initiative in 2021. The ‘Age Together’ study unearthed and prototyped propositions for “happy ageing” in assisted living facilities – enabled by various means of easily seeking help when it is needed. For example, visual check-in opportunities can be invited through a door designed to be left ajar, and conversations can be encouraged at a window with a ledge on both the internal and external walls.

The team recently completed a research project for Alexandra Hospital’s new campus. “It’s very refreshing that such a client will choose a studio that is not deeply entrenched in, say, medical planning. I think they are looking for a fresh perspective on how they can rebuild spaces and reconnect places with people,” says Yong.

For the Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA), STUCK Design investigated how to make better learning environments for the majority of public preschools in Singapore, which are housed in spaces carved out from the ground-floor void decks of housing blocks. In collaboration with local firm Freight Architects and Japanese firm Tezuka Architects, STUCK uncovered insights about how children could learn by playing and prototyped some of the ideas.

An eye on the future of creativity

Both Koh and Lee are currently teaching industrial design at NUS, but the studio’s activity in the education space goes well beyond this. Fuelled by the pursuit of impact, STUCK Design is a partner in Dsg’s Learning by Design programme for schools – an initiative that fosters creative problem-solving skills in students from primary to pre-university levels.

Even before engaging with this programme as a facilitator, the STUCK Design team had been working with schools to foster design thinking. Explains Lee, “We thought it was a good opportunity to help students think differently – to see how design can help them, and to understand that you don’t have to be a creative to be creative.”

Since 2020, Lee has also been a member of the Design Education Advisory Committee (DEAC), the first-ever national platform for design education thought and practice leadership launched by Dsg. The DEAC aims to shape the quality of design education and embed design into the nation’s education system – a signal of the recognised need to develop a workforce with the relevant creative thinking skills for the wider economy. “I say it’s my design national service!” says Lee.

An opportunity arose for Koh to give educators a glimpse of emerging digital processes to support creativity at the recent Design Education Summit organised by Dsg. He presented an artificial intelligence (AI) sketching tool that he initially developed for use by the STUCK Design team, but which he will be introducing to schools.

Aptly named Hypersketch, Koh developed it “to fulfil that part of the creative flow where designers still want to put pen to paper.” That is to say, to sketch kernels of ideas – a process that would often result in dozens or hundreds of Post-It Notes on the walls of a creative war room. “Other digital tools let you draw something properly once you already have an idea. But that front part, which is very fast and exploratory, was not really replicated. Hypersketch was first developed as a sketching app to fill that gap. You could draw even half a sketch or doodle, press the buttons, and simulate the effect of having 50 designers in the room producing sketches and suggestions.”

Now, Koh has developed it beyond the sketch into a tool for interpreting ideas in many different image formats. The same sketch of, for example, a curved line could be used to generate product or spatial illustrations. “It’s not meant to give you good answers. It’s meant to ask you: ‘Have you considered this?’ Then you can begin to edit and modify the output, feed it back in, and have the app generate a more refined idea,” he explains. “At some point, you have to ask yourself, ‘What is this thing in reality?’ Then you take it out and build it up in 3D software to really study it, work with its constraints, and make it real.”

The relationship between AI and humans is one where we have to co-direct the output. AI’s output could be good, bad, or incomplete. Even if it’s very good, it is not competitive because your friend or neighbour is able to press a button and generate the same thing. So it comes down to the back and forth – steering the output together so it’s distinct.

— Donn Koh

Though Hypersketch is still in sandbox stage, Koh has already encouraged his industrial design students to explore its possibilities. For example, a student carrying out design research on how residents use the void decks of HDB estates generated fictional void deck spaces with various characteristics, which allowed her to prompt and record user preferences. Koh himself has used the tool to produce quick visualisations for discussions with clients.

What corners of the imagination could such a tool unlock for students and future designers? There are infinite possibilities, but without question, it would cement the idea that far from feeling ‘stuck’ when it comes to creativity, anyone can participate in creative processes.

Read our unfolding series of stories on creative discovery and making life in Singapore ‘Better by Design’.