Ng Fong Yee Wants to Empower Kids to Design a Better Future

It is time that society takes children more seriously, says the designer who has learnt much from her years of teaching them. It has even led the DesignSingapore Scholar to further her studies in child culture design so she can eventually design with children as equal members of society.

As a student in Singapore schools, Ng Fong Yee grew up in fear. She was afraid of her teachers, anxious about forgetting to bring her textbooks, and feared getting punished from making mistakes. Classes were also unstimulating because they involved learning by rote.

This “awful way of experiencing growing up” and Ng’s struggles in academic subjects led her to pursue vocational training in visual communications instead. But when she subsequently moved to London to study for a graphic design degree, Ng was confronted by her phobias again. During her first year of studies, the undergraduate had to take a physical computing class that involved working with microcontrollers and programming computer code.

“Growing up, I would repeatedly not do well in math and that is why I had the mentality that I am not a math student and so I can never do coding,” she explains.

But this time around, Ng not only successfully completed the course, it even sparked her interest in such technologies. She began incorporating them in her school assignments, which culminated in “POMBOT”, her final-year project in 2017. POMBOT was a robot powered by a microcontroller to become an interactive mobile showcase, which Ng designed to overcome the fixed exhibition spaces given to each graduating student.

“When I was in London, school was a very safe space to experiment and fail and I really started to pivot,” she says. “I had gone overseas focused on becoming a print-based designer, but after the physical computing class, I wanted to know all about technology.”

The power of play

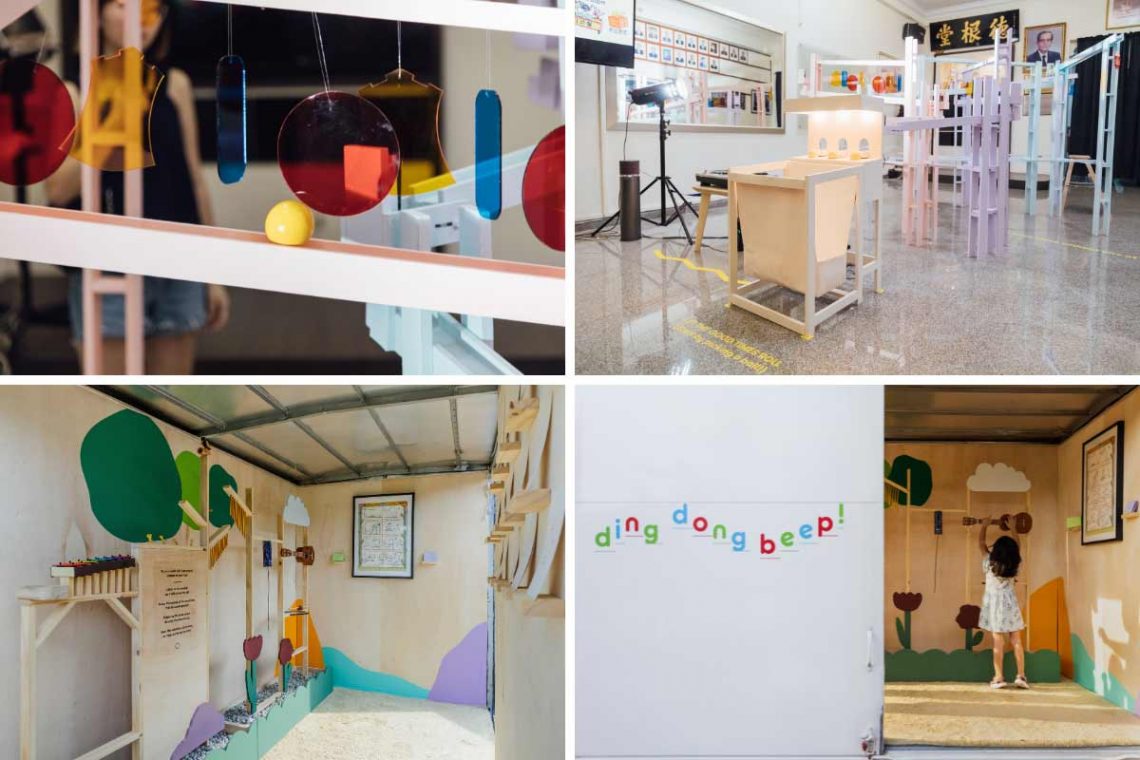

Ng continued exploring the intersection of design and technology after graduation and returning home. As part of Singapore Design Week 2019, she and a team of designers created an interactive installation for the Street of Clans Festival that opened the doors into four clan houses along Bukit Pasoh Road. When visitors joined forces to play the work Let the Good Times Roll in the Koh Clan, it would trigger a colourful kinetic display that expressed the clan’s belief in unity is strength.

More recently, Ng and two of her friends were behind “dingdongbeep!”, a mobile music room of toy instruments and artworks that encouraged audiences to discover fresh ways of playing with sounds. She helped design the installations that combined unusual placements of instruments and ambiguous elements like a string with googly eyes to prompt interactions and even questions.

Another project by Ng is dingdongbeep! (bottom left and right), a mobile music room that encourages audiences to discover fresh ways of playing with sounds. Photos by Marvin Tang, courtesy of Ng Fong Yee.

“Quite a lot of my work is public facing or interactive and I know I can never predict how people are going to react or respond to a work. By allowing room for uncertainty, you can be more playful in the design,” Ng explains.

This approach of learning through play, which runs through many of her projects, makes the experience more enjoyable and enriching for audiences, and even for her as a designer.

“Over the years, I’ve learnt that I need to be having fun and enjoying the process. That is quite a good indicator of how the project is going for me.”

Learning and unlearning with children

The importance of incorporating play into her design is influenced by Ng’s experience of working with children too. Alongside her design practice, Ng has taught children as the creative chief product lead and trainer at Saturday Kids, a company that offers creative coding classes for participants as young as five years old. In 2019, she also collaborated with Superhero Me, an arts collective that champions for an inclusive society. They used assistive technologies such as eye-gazing software and body movement tracking programmes to enable a group of minimally verbal and mobile children to develop artworks that were showcased as part of the inclusive arts festival PEEKABOO!.

As part of the arts collective Superhero Me, Ng also used assistive technologies to enable a group of minimally verbal and mobile children to develop artworks (bottom left and right). Photos by Marvin Tang (Superhero Me), courtesy of Ng Fong Yee.

For Ng, teaching children art, design, and technology is not about training them to be artists, designers, or technologists. Instead, it is to train them in skills to shape their own environment.

“It is showing them and equipping them with tools so they can then use it to pursue what they are interested in,” she says. “They have this toolbox that can help them go about solving problems, be it climate change or problems they face day to day.”

Although many parents are wary about exposing their children to digital technologies, Ng says they are here to stay and already part of our everyday lives. This presents opportunities to help children realise how to redesign the environment around them.

If you don’t show them how to use technology meaningfully, then how are they ever going to know how to do it? Maybe we should also give children a bit more credit in terms of how they are able to regulate or process their interactions with technology.

— Ng Fong Yee

Ng has been reminded of this many times in her interactions with children. Once, a five-year-old student of hers became annoyed while struggling to connect two devices via Bluetooth. He announced to those around him that he was going to try for another two minutes before getting angry.

“I was just so amazed by his ability to self-regulate and to communicate it. He didn’t just throw a tantrum and act out or give up… most adults can’t even do that,” she says.

“As adults, we bring a lot of assumptions and biases when we work with kids and even when we interact with them. But you will usually be surprised. Children are so multifaceted, and there is no one size fits all.”

Designing a more empowering child culture

Her respect for children as beings and not “unformed adults” led Ng to pursue a master’s in child culture design at the University of Gothenburg in 2023. She was attracted by the programme’s aim to explore the relationship between design and children’s perspectives. It is also in Sweden where the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child became part of the country’s law in 2020, and discussions are on-going about what this means for society.

Although one may think that only those qualified in early childhood development can work with children, Ng believes designers play a key role too.

“Early childhood education pedagogy is quite focused on a very specific, cognitive development of the child. But I think design takes care of what is outside the child. You need the designers who are making furniture, toys and the built environment to also come in and share their knowledge and expertise,” she says.

Ng will have access to such a network of local designers via the DesignSingapore Scholarship she received to pursue her further studies. She looks forward to working with other scholars to develop meaningful ways to co-design with children, be it on the creation of a playground to the healthcare system.

While advocating for children to be empowered as equal members of society, Ng recognises the desire and responsibility of parents and caregivers to protect them from danger too. She sees her role as highlighting these different needs of children and adults, and to design ways for them to work through such conflicts together.

“It is always the adult deciding what is good for the child. When the adult is the authority, then the kids don’t know how to assess, analyse and make decisions for themselves,” she says.

“The world is not black and white, so it’s really not about telling children this is right or not but giving them the tools and skills to discern for themselves,” Ng adds.