Dsg’s Formative Years Laid Strong Foundations for Singapore Design

What does a design council for Singapore need to be? That question was foremost in the mind of our founding Executive Director, the late Dr Milton Tan, when he took the reins of the newly formed DesignSingapore Council in 2003. His immense passion for nurturing a creative design culture in Singapore laid strong foundations for our work over 20 years – and counting.

Article by Narelle Yabuka.

Opportunities such as the one offered to the late Dr Milton Tan in 2002 don’t come around often. Seconded from his role as an Associate Professor of Architecture and Digital Design Media at the National University of Singapore (NUS) to the Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA – now the Ministry of Communications and Information, or MCI), he was appointed as the leader of the new DesignSingapore Taskforce.

His task? It was nothing less than to set the national agenda for design at a time when doing so could not have been more crucial.

An economic and cultural shift

That year, the National Economic Review had established that the creative industries were a new economic growth area for the nation. There was an impetus to develop Singapore into an Asian hub for design excellence, offering a cluster of design services. Tan was asked by MITA to study the lay of the land for Singapore design and conceive strategies to develop the sector. He would subsequently implement a spectrum of initiatives as the founding Executive Director of the upcoming DesignSingapore Council (Dsg), which was established in 2003.

It was a turbulent time for national economies – particularly in Asia – and a cultural inflection point in global terms. The 1990s had witnessed major shifts including the rise of information technology, increased globalisation, the dot-com bubble, the Asian financial crisis, and the SARS epidemic. In the context of unfamiliar challenges, the new knowledge economy had arrived, and participation in it required ideas and creativity rather than industrial might alone. National competitiveness had to be considered in broader terms, and creativity, including design as one of its higher-order applications, was a key piece of the puzzle.

Tan’s crucial insight for Singapore was that while Dsg would do the work of supporting the further development of practical design skills and design excellence, it would also have a bigger and more challenging role to play. Through its work, Dsg needed to seed an awareness of and resonance with creativity and design in the national consciousness. It also needed to support the growth of a design ecosystem – an environment in which design activity could be nourished and flourish.

Nurturing a national design culture – with both economic and social agendas – would help grow the creative capacity for sustained competitiveness in a knowledge economy. Tan realised that the government’s role in supporting design needed to go beyond the creation and promotion of manufactured objects, where its focus has been through the earlier industrialisation efforts of the Economic Development Board and International Enterprise Singapore (formerly the Trade Development Board).

The environment to foster post-industrial creativity is very much harder to create and maintain than that for industrial manufacturing. Creative thinking, say, for design, is not just a production process… but also needs vibrant social and cognitive milieus that are talent centric.

— Dr Milton Tan

Photo: Dsg.

Seeding design culture

Dsg’s formation in August 2003 as a department of MITA was a turning point for design in Singapore. Backed by a board of leaders from design, business, and government (chaired by Edmund Cheng of Wing Tai Holdings), Tan set about the unprecedented task of implementing the ‘DesignSingapore Initiative’ – to establish Singapore as “a global city for design creativity and excellence in Asia where design improves capability, enhances quality of life, and drives national competitiveness”.

Tan spent seven energetic years steering Dsg as its founding Executive Director, and in that time he and his growing team strategised, conceived, trialled, and implemented a wide spectrum of initiatives aimed at developing design talent and intellectual property, promoting Singapore design and designers, and seeding a healthy design culture.

Singapore designers suddenly found an array of possibilities to access international training via the Dsg Scholarship, and international markets via grants to support the presentation of their work at top international design platforms. Through Dsg, many could also hone their skills in guided studios, compete in competitions, and receive recognition for design excellence through awards, such as the President*s Design Award.

There was a new landscape of opportunity to attend and participate in international platforms including design conferences (such as the Icsid [International Council of Societies of Industrial Design] World Design Congress in 2009) and exhibitions and festivals (such as Dsg-initiated group showcases for furniture design in Milan and architecture in Venice).

An important anchor event for Singapore was the Singapore Design Festival, established in 2005 and running every two years as a platform to unite designers, their clients, and the public. Buoyant with exhibitions, talks, workshops, and product launches, it continues today as Singapore Design Week, happening annually in September.

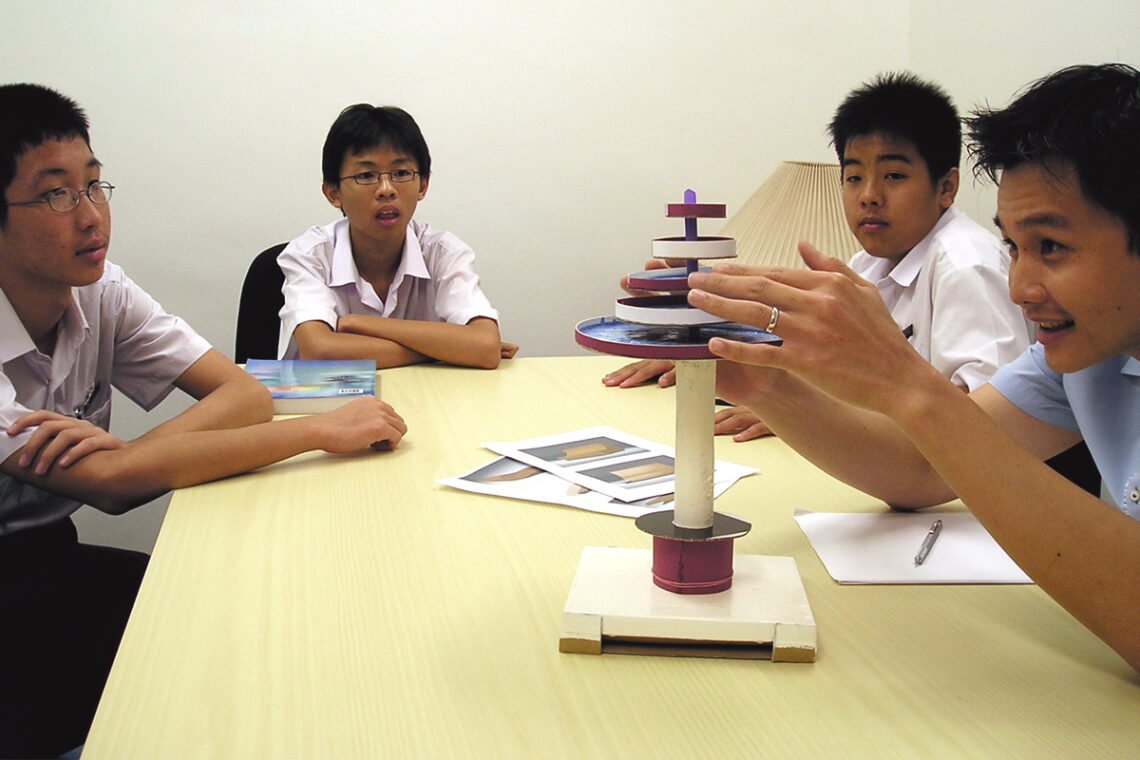

Meanwhile, businesses were able to understand and access design as a strategic tool for competitiveness via conferences, workshops, and dinners organised by Dsg, and via programmes developed by Dsg in partnership with IE Singapore and SPRING Singapore. Students were introduced to conceptual thinking through the Many Ways of Seeing workshop series initiated personally by Tan and run by Singapore Polytechnic. The public was invited to think about everyday life anew through design through the project 10 TouchPoints – a nationwide endeavour to improve public amenities through design.

Behind the scenes, Tan and the Dsg team were laying the foundations for anchoring international design organisations in Singapore (including BMW-DesignWorks, the International Federation of Interior Architects/Designers [IFI], and Red Dot, which continues to run both a museum and its Design Concept award here); seeking key partnerships for strategic design cooperation with other countries and organisations (Vitra, the Korea Institute for Design Promotion, the Government of the Australian state of Victoria, and the Danish Government); bringing together the disparate community of local design-industry associations; conducting surveys and studies locally; embarking on international study trips; and drafting recommendations for design policy.

The mid-2000s were an exciting time for design in Singapore, with Dsg’s national-level design initiatives balanced by ground-up ones such as independent exhibitions by design studios and new locally produced design magazines. Suddenly, Singapore design was featured in the local dailies, on mainstream TV channels, in the international press, and around the city. The world’s leading designers were coming to Singapore, and Singapore designers were showing their work in the global arena.

Just three years into Tan’s tenure, Singapore had climbed upwards in the Designium Global Design Watch ‘Design Competitiveness Ranking’ of 2006, from 22nd place to 16th. By 2009, when Dsg published its second strategic blueprint for the DesignSingapore Initiative (titled Dsg-II), leading international design figures were able to observe the stunning progression of Singapore’s design industry. Arnold Wasserman, Chairman of design strategy and innovation agency The Idea Factory (San Francisco and Singapore), was quoted in the blueprint: “DesignSingapore has done a terrific job thus far in accelerating design from near zero to 100km/hour… In an amazingly short time, you have brought Singapore parallel with nations that have centuries of design heritage.”

It was clear that a design ecosystem and culture was emergent in Singapore. In addition to the direct impact of the programmes he oversaw and the soft impact of the advocacy roles he performed, Tan’s personality and approach unquestionably contributed to the atmosphere. With Tan at the helm of Dsg, what could have been formulaic and formal was anything but. Under his leadership, the cultivation of Singapore’s design culture was itself a process of design.

Tan’s son, Ryan Tan recalls, “You could really sense that there was electricity in the air when Dsg was doing something because it was so different from all the other government agencies. Whatever Dsg set its mind to, you knew it was going to be totally different.”

A professional and personal legacy

On 8 November 2010, at the age of 56, Tan sadly succumbed to leukaemia – a loss acutely felt by all whose lives he touched. An obituary published in The Straits Times on 10 November quoted his colleague, former Dsg Director Yeo Piah Choo: “Milton was a champion of design in Singapore. To me, he wasn’t just my boss, but also a mentor and a friend.” On 11 November, some 85 of his colleagues and friends from design and government published his photograph and a quote from his blog in the same newspaper:

Creative people alter the way we see the world. They introduce the surprising, even shocking, alternative to the things we take for granted as permanent and unchanging. It must be said that it does not always work, but when it does, our world gets turned on its head. Suddenly, we wonder how we had put up so long with the bad and ugly. Often, we even cry, “Why didn’t I think of that?”, or, “I could have done that!” But the sad fact is that we did not, and the truth is that creativity is much harder than it seems.

— Dr Milton Tan

Said the tribute, “This is how we will remember Milton Tan… Milton will always remain an inspiration to all of us.”

Looking back, it is hard to imagine anyone but Tan as the right person for the job of founding Dsg. His family puts it down to his passion for Singapore that extended into design, his curiosity about all of life’s possibilities, and his tireless drive to convey the meaning and purpose of design. His son Jason Tan remembers, “Dad was passionate about design everywhere. He would call out overlooked little things that intrigued him, such as the narrowing and broadening of a shopping mall’s winding corridors; why a sheltered bus stop had been placed under a covered walkway that was under an expressway; infestations of green exit signs; or the different designs of disposable cutlery. In all of these examples, he was alluding to how people interacted with design; how good design is invisible and bad design is instantaneously noticed.”

Certainly, Tan’s efforts to steer a new organisation though uncharted territory were also aided by his background of teaching and academic administration at NUS. Building on the experience of his PhD studies in ‘design creativity’ at UCLA and Harvard Graduate School of Design under design and computation leader Bill Mitchell, Tan had been instrumental in pioneering the computer-aided design and industrial design courses at NUS. For Tan, like his students, learning was a constant. The unknown was to be embraced – never feared.

As Ryan recalls, “He was always filled with playful creative energy and joyful inspiration. No idea or dream was ever off-limits when it came to silly brainstorms with my brother and I. He would say, ‘The very best serious ideas usually spawn from the silly ones. Treat every idea, and those who have them, with respect and great care.’”

Tan’s big heart and thought for others is fondly remembered by his wife of thirty years, Dorothy, who journeyed with him from Nottingham in the UK (where they first met as students) to Singapore, to Los Angeles and Boston (for his PhD studies), and then back to Singapore – and through the voyage of his work at Dsg (even tagging along on some of his overseas trips).

She recalls, “In his travels to different cities to visit designers, if Milton knew that there were Dsg Scholarship recipients there, he would contact them to meet up for a meal to find out how they were getting on and to encourage them. When Milton was at Harvard, he took time to check who would be coming from Singapore to study at Harvard, MIT, or Boston University. If these people were arriving in Boston late in the evening or at night with children, Milton would pick them up at the airport even though he did not know them or even what they looked like! That’s how big Milton’s heart was.”

Dorothy also fondly remembers Milton’s care for his students at NUS. “When he knew his students were working late into the night on a project in the studio, he went to buy supper for them. I later found out that he even supported his students financially to go on trips to study architecture. We now have a scholarship and awards at the university under Milton’s name,” she shares.

The key resource of a good place is not physical, but time. It is not just what’s there, but what one can do there over time… The critical resource of time brings people together. It builds lasting relationships, spontaneity, and trust. These are the pre-requisites of a creative culture.

— Dr Milton Tan

Tan’s generosity of spirit and barometer for the deep value of human relationships (an essential ingredient of any culture – be it design or otherwise) emerged, of course, during his time at Dsg, too. His family is particularly enamoured of the parting gifts that he bestowed upon the members of Dsg’s International Advisory Panel (IAP – a group of international design leaders and experts curated by Tan, who provided strategic guidance on design development in Singapore) when their service concluded in 2009. He purchased blank Trexi figurines (then the popular flagship toy of Singapore-based company Play Imaginative) and devised a way to use the rotating toy head as a world clock. This allowed each IAP member to simultaneously read the time in their home city.

“I remember that Milton and I escaped to Art Friend very early one morning before any customers arrived at the shop to get the materials he needed to make the clocks. Milton was quite sick then with low immunity, so we had to avoid crowded places,” recalls Dorothy. She continues, “It was his joy and love to make and build things for others.” The family keeps and treasures Tan’s own Trexi, signed by each IAP member.

For a sense of Tan’s overarching perspective and driving preoccupations, an illuminating reference is a video of the last public speech he delivered in August 2010 – a TEDxSingapore talk at Old School, Mount Sophia. It captures many of the core ideas he shared in his personal blog that year, which Ryan and Jason have revamped into a larger site that also encompasses the Milton Tan Memorial Fund.

Ryan recalls of the TEDx talk, “Despite being ill, Dad really wanted to respond to the invitation to speak. We had obtained the doctor’s approval prior to going and we were delighted by the strong turnout… Dad’s voice was weak, but he spoke with pride and conviction about what we feel was his life’s work: ‘Where do ideas come from?’”

“Ideas are all around us,” Tan conveyed to the audience, “but it’s like saying knowledge is all around us. Why is it that some people have greater access – they can see more ideas than others?” With his characteristic humour and an artful reference to the right/wrong basis of much of Singapore’s schooling at the time, Tan described some of the methods that designers use to generate their concepts, explaining the cognitive process of emergence as well as the sometimes-contestable nature of what we assume to be true and stable.

He closed by discussing the culture of creative ideas – the strategic environment needed for generating them – as a four-way matrix of the active, propositional, reflective, and representational. These qualities, he suggested, find their natural homes in the design studio, the design museum, the design conference, and the design library. “You need all these four at the institutional, organisational, and personal level,” he said.

In this statement we can appreciate the thinking behind the wide breadth of programmes Tan developed at Dsg. The studios, exhibitions, publications, and talks he conceived would collectively, bolstered by his design administration activities, bestow upon Singapore a healthy soil for the flowering of design culture. Detailing every one of his initiatives and intents would require a book, but if one were to embark on such an endeavour, they could be sure that Tan would have approved of the library contribution. Documenting Dsg’s key initiatives with publications was a standard practice under his leadership, Yeo recalls, and in Tan’s eyes, the aim was for every publication to be of an award-winning standard!

Evolving for the future

In 2023, Dsg continues to run key programmes launched by Tan alongside new programme iterations that build on the foundations he established – among them, the Learning by Design programme for schools, the community-focused School of X, and the Good Design Research initiative for designers. Singapore, having been classified as a UNESCO Creative City of Design in 2015, and seeking the innovation that will keep it afloat in a new age of climate crisis, ageing, and digital evolution, again looks to design’s contributions to a better future.

Simultaneously, global spotlights point towards Singapore, often focusing on our successful prototypes of urban density with integrated greenery and our national-scale digitisation efforts – two areas where design has already been critical to national success. Yet the story of how design shapes Singapore’s future continues to be written – as it should be – often in tandem with other sectors in a complex web. Design’s performance in this system is underwritten by the maturity that twenty years of design sector development have guaranteed.

When looking forward, we may again look back to Tan, who in 2007, launched a new focus on ‘Design Futures’ at Dsg. The aim was to encourage upstream design research and development, and to cultivate a long-term focus on strategies and content that could create competitive advantage for Singapore designers and businesses. It is a strategic direction that continues today through Dsg’s new key focus areas of sustainability, emerging technology, and care, and in the Design Futures pillar of Singapore Design Week.

In one of his last major Dsg projects, the Icsid World Design Congress Singapore 2009, Tan and his team at Dsg alongside an organising committee chaired by designer Low Cheaw Hwei, elected to break from convention with a future-gazing theme and a purposely fragmented conference format. The ballroom at Suntec Convention Centre was shaped into a fan of nine studio pods around a central stage and seating. The Design2050 Studios, led by renowned designers, developed research-driven design propositions for the year 2050 in response to a spectrum of challenges, including mobility, rising sea levels, farming, healthcare, and more.

Wrote Tan prophetically in his foreword to the Icsid Design2050 Studios publication: “The Design2050 propositions will be a growing repository of design futures – ideas about how we should live, work, and play; improve personal and corporate communication; simplify things and processes; take care of our environment; make people happy. In this sense, it will be a leading example of a knowledge base for the future, to be built and used recursively by students, researchers, practitioners, enterprises, and policy makers.”

Thank you for your legacy, Dr Tan.

Read our unfolding series of stories on creative discovery and making life in Singapore ‘Better by Design’.