From his early years as a DesignSingapore Scholar to his current roles as a practitioner, teacher, and curator of design, Hans Tan has spent his career deciphering, developing, and sharing an insightful perspective on what design can be and do. Now, as the Curatorial Director of the Design Education Summit 2023, he is sharing the message that creativity is in everyone – and design is one of the best ways to apply it.

Article by Justin Zhuang.

A common fear of design students and those interested in design is that they are not the creative type, says Hans Tan. The designer and design educator is saddened each time he hears someone express this.

“These people have been misinformed that creativity is something they don’t have inherently – that only some people have it, or it is only related to the arts. This is not true,” he says. “Everyone is creative, and creativity can be improved with practice and training, like most skills.”

Tan himself is testament to this. As a student who excelled in physics in secondary school and commerce in junior college, he had secured a place to pursue a degree in business. Then, by chance, he encountered a National University of Singapore (NUS) prospectus advertising its industrial design course. Despite having no knowledge about design, he was curious enough about the prospectus’ claim that the field can bring together engineering and business that he switched courses – a decision that changed his life.

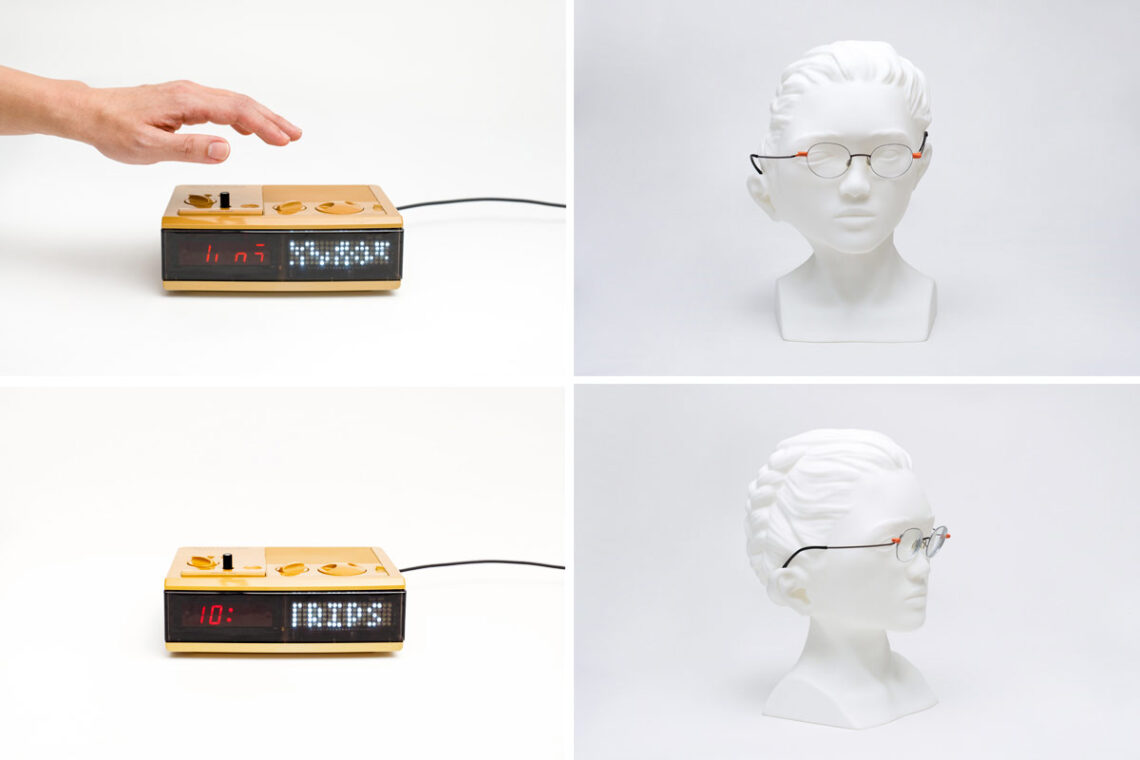

Today, Tan is recognised as one of Singapore’s top industrial designers. He is best known for using innovative methods to craft highly original designs that tell stories of local material culture. Examples of this range from his Spotted Nyonya series, for which he uses sandblasting to transform traditional Peranakan vases into contemporary objects; to his Pour plastic table that is cast without a mould, similarly to how colourful kueh lapis sagu (the popular local layered confectionery) is made.

Tan has also ventured into design curation. During the pandemic and with support from the DesignSingapore Council (Dsg), he curated the first edition of R for Repair – an exhibition series that encourages people to rethink their relationships with objects and the role of repair in design. Designers were given beloved broken objects donated by the public for creative repair, which were later returned to their owners in a new state. R for Repair was showcased at the National Design Centre in 2021.

Subsequently, Tan teamed up with UK-based co-curator Jane Withers for a second edition of R for Repair that involved designers from both Singapore and the UK, as well as broken objects from both places. This exploration of creative cultural exchange was showcased at the Victoria and Albert Museum during London Design Festival in 2022.

Spotted Nyonya, Pour, and R for Repair have all received the President*s Design Award (P*DA) ‘Design of the Year’ accolade – in 2012, 2015, and 2023 respectively. In 2018, Tan was also named the P*DA ‘Designer of the Year’ in recognition of both his studio practice and contributions to design education.

Crafting his own Singapore designs

Such achievements and accolades, however, were far from Tan’s mind when he first started his career. After graduating from NUS in 2005, he pursued further studies at the Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands on a DesignSingapore Scholarship. Tan was among the very first batch of students to receive a DesignSingapore Scholarship that year. The masters programme introduced him to a more conceptual design approach that expanded on the problem-solving design skills he had acquired in Singapore. When he returned home two years later, he set up his eponymous studio to practice in a similar manner.

“I wanted to explore making and craft as well, but I acknowledge that in Singapore we no longer have the history and culture of crafting embedded in the design industry,” he says. As a result, he started making his own designs. This required him to learn fabrication processes and understand the raw materials he works with, which are often the starting points for his projects.

“In most of my work, I design with the process and experiment to see where it leads in terms of outcome,” he explains. This design approach of “seeking opportunities instead of solving problems”, however, was not well understood at first in Singapore. “I was in a weird space between design and art. Designers would think I was working as an artist. And artists would say, ‘No way, you are making functional things like a designer’,” he recalls.

One of the reasons for my motivation to make things on my own comes from the fact I can’t make with others. In Singapore, it is very difficult to find people to make with. We have very little of that system. My response as a designer is to design things in a way that allows me to make them myself. It’s made me more interested in the process of making then the material I am working with.

– Hans Tan

Growing with the design industry

Nonetheless, Tan persisted and gradually found opportunities to showcase his designs to a wider audience. He also began teaching at his alma mater to impart his design approach to the next generation. Nudging at the boundary between the practical and conceptual, he once led a workshop in which he asked NUS industrial design students to carry out a series of progressive exercises to reimagine what a vase was. The resulting conceptual designs were exhibited to the public as part of the Singapore Design Festival 2009 (the precursor to Singapore Design Week).

Over the years, as more designers emerged to push the boundaries of the discipline, the local design scene has evolved and expanded, says Tan. For instance, banks and hospitals now have their own design teams helping to innovate and improve internal processes. He believes such proliferation of design in all areas of life should be further encouraged.

The design ecosystem has changed a lot since I came back from my studies. It has become much more varied and this has opened up more potential for practitioners to do a wider variety of things, particularly in using design as an integrator.

– Hans Tan

“Design is really well placed to be a catalyst and bring a different point of view to all areas,” says Tan. He adds, “I often say the role of a designer is as an interface between people and the things people create. We are mediators or the medium to connect the two.”

Nurturing creativity through design

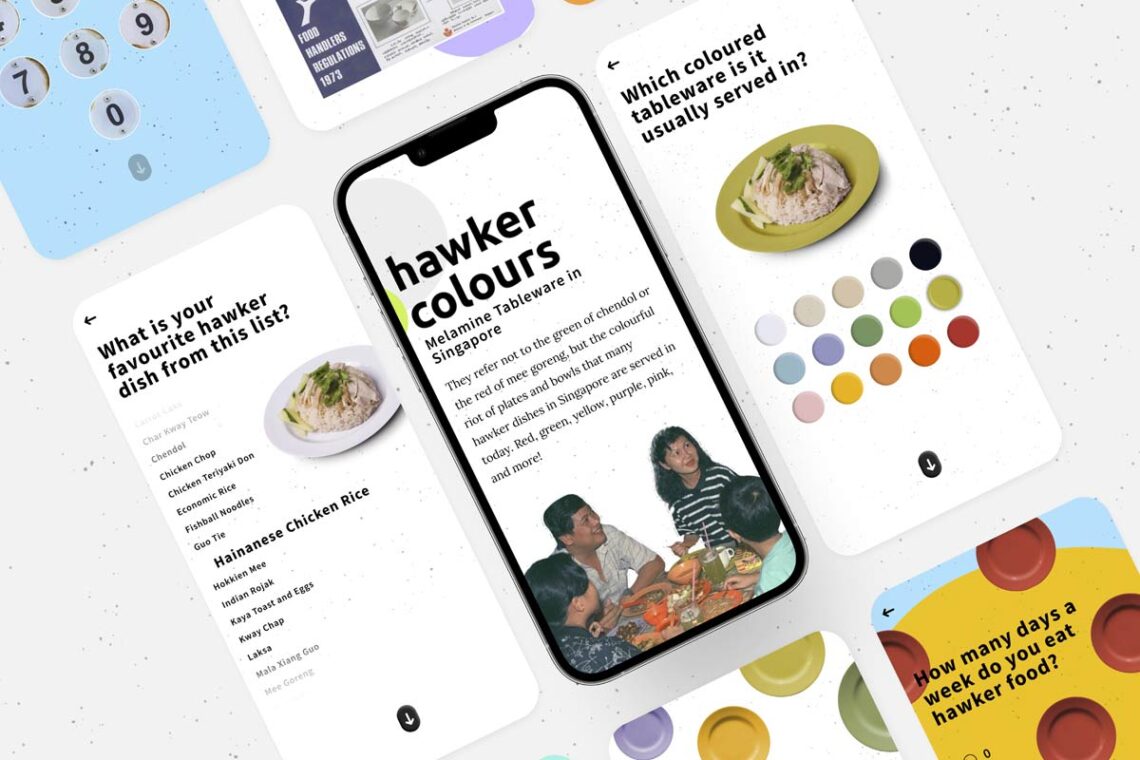

While better known for his designs that express Singapore culture, Tan will showcase his other long-standing interest in “designing minds” this year. The Associate Professor at the NUS Division of Industrial Design is the Curator of the Design Education Summit (DEST) 2023, a biennial event organised by Dsg to connect educators of all levels with design. This year’s theme, “I am NOT Creative”, expresses Tan’s goal to dispel the popular misconception that only a chosen few possess creativity.

“As long as you have imagination, you have creativity. If you cannot imagine, you cannot plan what is happening the next hour or even tomorrow,” he says. “You just need to recognise it, have confidence in using it, and practice it. When you apply it to the real world, that’s when imagination becomes creativity.”

And one of the best ways to practice creativity is through design, adds Tan. With its codified methods, tools, and processes, such as the popular design thinking framework, anyone can easily and systematically become more fluent and confident in applying their creativity. Moreover, design also introduces other skills, such as empathy and iteration, which link creativity with the wider ability to solve problems.

Tan makes mention of the Design Fundamentals class he has run for first-year industrial design students over the last six years. Students are asked to design a “fantastic flour” outcome during a six-week course in which they are guided to experiment with the process of steaming to shape the common baking ingredient. This hands-on approach to experiencing the typical design process of working with materials and industrial methods helps students learn better as they are “thinking through making” – an outcome proven through research.

“In a project like that, you cannot imagine what will happen to the flour. Some interesting additive ingredient or the reshaping of the steamer might produce something quite different. But you won’t know until you do it,” says Tan. The iterative process also helps students figure out how to deal with ambiguity and even failure, particularly as many have no experience in cooking or baking and are working with flour for the first time.

My Design Fundamentals class is not just about learning design skills and approaches, but also building mentality and a mindset.

– Hans Tan

This is also one aspect of learning design that Tan feels should be talked about more. Besides acquiring important characteristics such as empathy and creative confidence, those with design literacy are empowered to make the world better. This ability to make change is what many students are yearning for, he says.

“We know through a lot of research that making meaning is extremely important to the next generation, above many, many other things like job stability or higher pay,” Tan explains. “The ability to believe in yourself and feel that you can make change is an extremely important aspect of design. You can even apply it to your life!”

Read our unfolding series of stories on creative discovery and making life in Singapore ‘Better by Design’.