What a week at Lord Norman Foster’s Foundation taught me

DesignSingapore scholar Jonathan Ng recounts his experience as a participant in the Norman Foster Robotics Atelier 2019 in Madrid, Spain. He was one of 10 scholars selected through a global open call to participate in the workshop, where he met the acclaimed architect. Jonathan is currently pursuing a Master in Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

DesignSingapore Council (Dsg): Tell us about your experience. What was the focus of the 5-day workshop?

Jonathan Ng (JN): The third edition of the Norman Foster Foundation (NFF) Robotics Atelier gathered 10 scholars drawn from diverse backgrounds, from architecture to the arts and humanities, to explore new opportunities for combining emerging technologies with experimental fabrication processes.

Our focus was on large-scale, 3D printing using recycled ocean plastics. In teams, we were challenged to design 3D-printed building-skins that imagined how rapid, large-scale additive manufacturing might change the existing paradigm of construction towards one that is functional and yet beautiful and sustainable.

JN: My team was interested in challenging the topic of building component integration, where a typical building element comprised hundreds of tiny individual parts. Titled “50 to 1”, our building-skin prototype sought to reinvent the window and building frame by integrating structure, M&E (mechanical and electrical systems), piping and framing into a unified element.

The premise was that through design, we could build more with less. Furthermore, by experimenting with auxetic patterns and the meta-material properties of 3D printing, we sought to bring a new tactile experience to opening a window.

Dsg: Tell us more about your team’s process in developing the building skins.

JN: Rather than just slicing and 3D printing our geometries using typical software, which typically results in a normal solid shell, we wrote custom codes and designed individual print toolpaths and textures for our new building skins.

This allowed us to exploit the capacities of the machine and fabrication method to its full potential, using less raw material while giving us greater control over the form and function of the final prototype.

Working through physical tests and scaled 3D prints via the desktop printers at the NFF, we quickly tested and refined our ideas.

After numerous rounds of rapid prototyping and finetuning throughout the week, it was time to scale up! We moved from the NFF office to the Nagami Robot Factory and started printing 1:1 full scale building components using a 6-axis industrial robot.

It was a fascinating experience to see such a large robotic 3D printer in action, churning out 4mm thick layers of transparent PETG at rapid speed and slowly bringing our ideas to life.

The grand finale was the group presentations where we showcased our research and prototypes to Lord Norman Foster and the various academic members.

There was a fantastic discussion on the numerous possibilities of large-scale robotic 3D printing as it is becoming an increasingly viable solution.

Some of its potentials included:

- Its ability to transcend geographical limitations while capitalising on local materials and local construction practices;

- The freedom of form that creates new expressions of beauty, unlocking new means of enhanced environmental performance and at increasingly attractive costs; and

- The capacity to integrate parts and thus the ability to consider a building’s end-life right from the design stage, thereby exploiting sustainability to its maximum rather than just an afterthought.

For transformational impact, we must fundamentally change the way we think about design using technology. We need to … fully exploit the capabilities and capacities of new design computational approaches.

Dsg: What was a key takeaway from the experience?

JN: For transformational impact, we must fundamentally change the way we think about design using technology.

Rather than merely thinking of mechanisation, translating age-old manual methods into a digital format, we need to shift our focus to smart computing and fully exploit the capabilities and capacities of new design computational approaches that capitalise on both machine and human intelligence, to ultimately create a better future for ourselves and our built environment.

Dsg: What was your biggest highlight?

JN: My biggest highlight was the opportunity to interact with Lord Norman Foster. It was incredibly inspiring that despite his age (84) and accomplishments, he was a wonderfully inquisitive and humble person.

He shared the importance of having conversations with people beyond our profession, something that he practices himself, so as to learn from other people who might already have asked the same questions or have solutions to problems we have yet to fully comprehend.

In addition, despite the strong focus on technology in the Robotics Atelier and even in his practice, Lord Foster emphasised the importance of technology as a means to social ends – that its ultimately role was for society, whether it be via sustainability or enabling new forms of interaction and community.

A close second was the firsthand access to the Foundation. The NFF showcased an incredible collection of Lord Foster’s work through the years, from his early years at Team 4 to the collaborations with Buckminster Fuller and even the latest projects coming out of Fosters + Partners, such as the upcoming Apple Park in California.

I loved being able to trace how different proposals changed along with technological development through time, whilst providing inspirations of how we might solve problems in the years to come.

Finally, the opportunity to interact with the Atelier mentors, Xavier De Kestelier and Manuel Jiménez García, as well as the opportunity to engage with the other scholars, who were experts in the fields of computational design and digital fabrication.

It was a fantastic experience and opportunity to learn more about the latest cutting-edge research each of us was working on and to discuss the future of computation and digital fabrication in architecture.

Dsg: Did the experience inspire you to do something different moving forward?

We are at a point in time where digital tools and technologies have matured. The primary issue now is not so much about technical capacity but rather where and how we deploy this technology.

In the built environment, there are critical areas that desperately need our attention and as designers, we can no longer just rely on existing technologies. Instead we need to radically rethink our current ways of working.

A week of intensive designing, building and discussing with amazing people has also taught me that finding good solutions begins with asking the right questions.

Furthermore, as new digital tools collapse the barriers between the disciplines, I believe it is more important than ever for architecture to develop a deeper integration between design, fabrication and construction while constantly questioning the way we build.

Beyond just the technological discussions in the week, an interesting learning point was that perception is an incredibly important aspect of sustainability.

Case in point was the sharing by “Parley for the Oceans”, a company that has successfully rebranded recycling of waste ocean plastics as something of high value, a luxury good, via its amazing design, a rich network of partners worldwide and collaborations with great brands such as Adidas.

Rather than framing sustainability as a responsibility, i.e. that we should consume less for the sake of the environment, sustainability can be reframed to something that is beneficial and even desired. This insight was one I did not expect but was incredibly insightful and impactful to my thought process.

Dsg: Finally, could you share an update on your Master in Architecture at Harvard.

JN: Apart from my architectural coursework as part of my Master in Architecture, I have been working on research on Robotics for Adaptive Robotic Carving.

I have chosen to highlight this project as I believe this is the next frontier for robotics. Current fabrication machines can execute specific-given instructions to a high degree of precision, i.e. they rely on predictable and controlled parameters and environments. However, much of our external world isn’t always like this. So how might one extend robotics’ capacities to match the real-world environment?

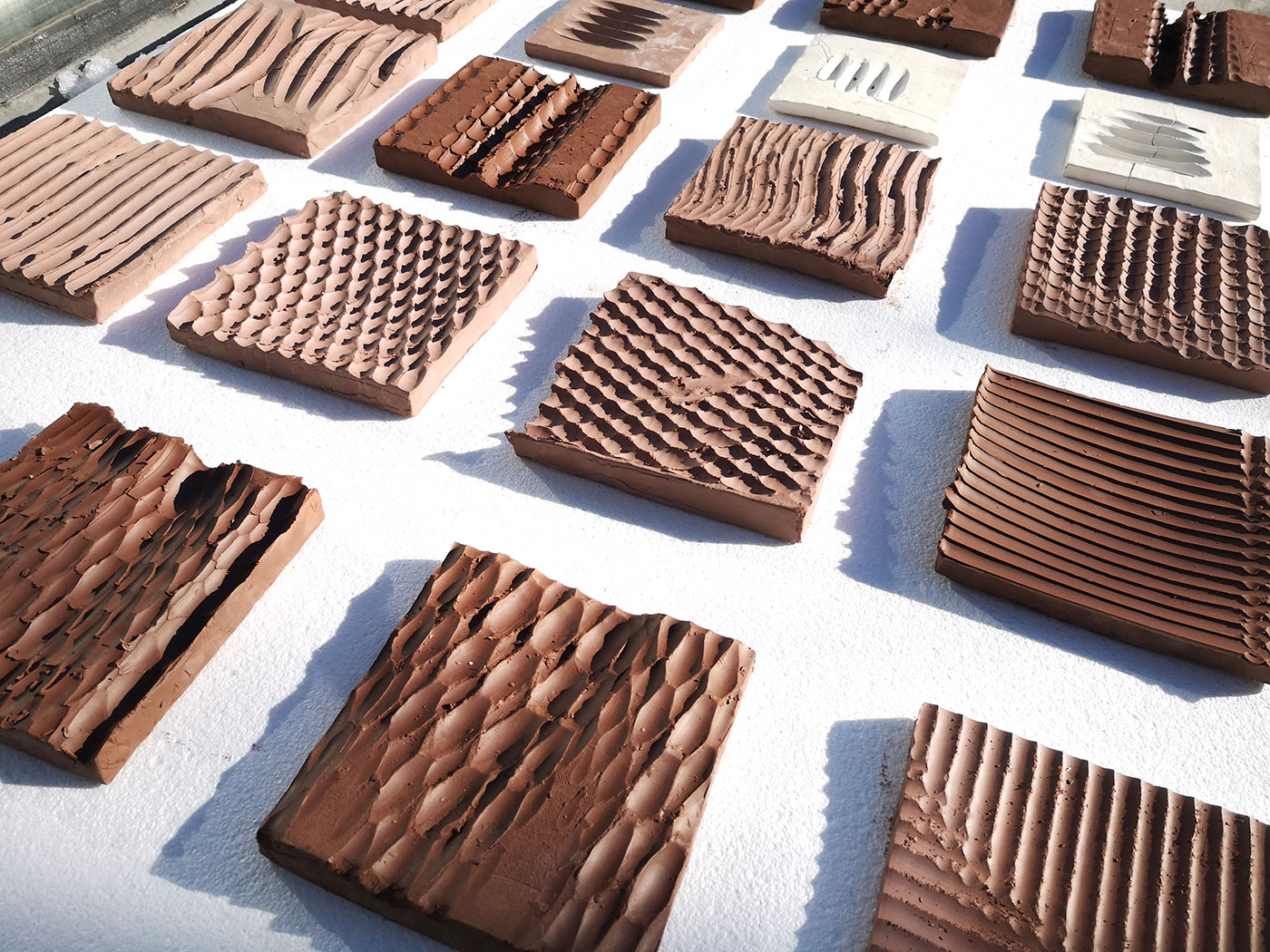

My work explores the field of agile robotics – using real time computational sensing and machine vision to enable robots to sense and adapt for non-uniform material properties. The material I used was clay, for its malleable yet inconsistent materiality.

In a series of tile tests (seen in the image above), the robot iteratively 3D scans, interprets the existing clay “terrain” and automatically computes a new carving path. This allows the process to have a high degree of control, detail and repeatability despite its material unpredictability. Furthermore, the method creates new marks and patterns which could not be made by human hands or any other digital processes.

This research hopes to achieve the following goals:

- Expand the opportunities of digital fabrication for new materials, such as ones which have been left out due to their “unreliable” properties, and

- Open the door to new forms of human-machine interaction, for example where a clay artist might work simultaneously in tandem with a robot with each reacting to the marks made by the other in real time.

The research and its outcomes are set to be exhibited at the Harvard Ceramic Studio in Spring 2020.

For more information on DesignSingapore Scholarship, please click here.