Veerappan Swaminathan’s Repair Movement Mends Appliances and Builds Community

A former mechanical engineer with a mission for sustainable living has designed a repair movement in Singapore’s heartlands. Veerappan Swaminathan, co-founder of Repair Kopitiam, with a team of repair coaches, orchestrates a growing series of repair clinics for the public. Beyond diverting trash, the programme builds awareness of throwaway consumption and appreciation for good product design. Even better, it nurtures a community of changemakers eager to expand the movement’s reach.

Article by Narelle Yabuka.

Have you ever marvelled at how common repair skills are in science-fiction films, such as the Star Wars series? If the blockbusters are anything to go by, when we live inter-galactically in the future with little more than we can carry in our spaceships, it will be a necessity for us to fix what breaks and reuse every component we can. We’ll all know how it’s done.

Few of us live with that attitude or those skills now, on Spaceship Earth. It’s not entirely our fault as consumers; many objects are designed to be unrepairable. But there are some impressive efforts to change our throwaway habits (where possible) from the ground up. One notable example is right here in Singapore.

A culture and community of repair

Veerappan Swaminathan is a mechanical engineer by training, but these days he is more akin to a pioneer exploring the frontiers of community engagement via sustainable living principles. Specifically, he is nurturing a culture of repair and a community of people empowered to help each other overcome throwaway consumption. In short, he is creating a movement.

In 2014, he co-founded the Repair Kopitiam initiative, which guides the public on how to fix their broken items at free monthly pop-up clinics in public housing estates. Swaminathan and co-founder Farah Sanwari (who has since stepped aside) took inspiration from the similar Repair Café initiative founded in the Netherlands, but for Repair Kopitiam, that model has been tailored to the nuances of Singapore.

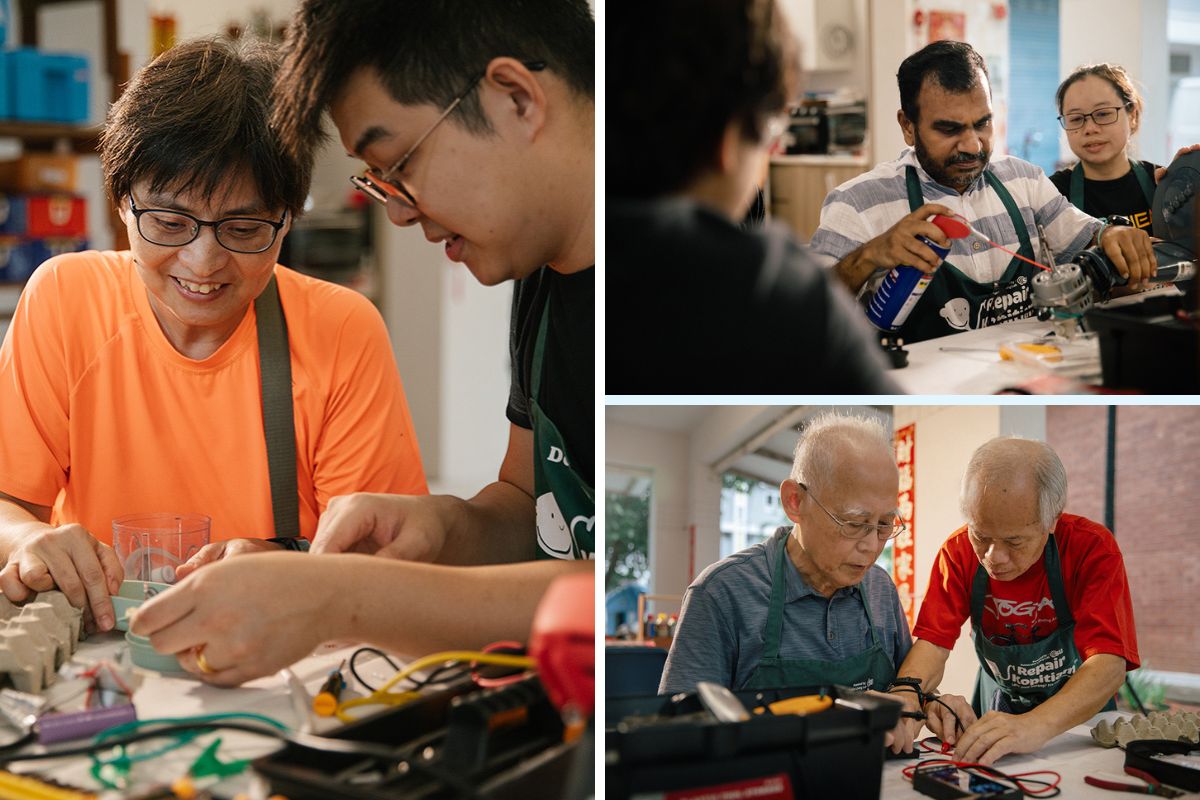

How does it work? The engine of the initiative is a community of some 1,200 repair coaches, which the Repair Kopitiam facilitation team has built up through a rigorous coach training programme. On the last Sunday of every month, anywhere between 100 and 200 of the coaches (depending on venue capacities) will disperse to 11 locations1 around Singapore, spending one-to-two hours with every member of the public who has booked a slot.

In a good sign for sustainable living, there’s no shortage of demand. Slots for consultations with repair coaches are typically snapped up within a few days of being released on the events page of the Repair Kopitiam website. People are keen to have their broken-down fans, kettles, vacuums, and blenders fixed – these being the top items that are brought in – alongside vintage pieces such as old radios, vinyl players, lamps, and laser disc players.

Truth be told, the primary driver for people seeking a repair, according to Swaminathan, is saving money. Sentimentality comes in next on the tally of incentives, before environmental considerations. But that doesn’t alter the fact that during Repair Kopitiam’s ten years of operation to date, approximately 3,600 electrical items have been saved from the trash.

Perhaps even more significant is the exposure of thousands of people to the culture of repair, and the development of a substantial community of repair coaches who will have ripple effects in their own networks. This, after all, is the soul of Repair Kopitiam.

We focus on telling people, ‘You don’t truly own what you can’t repair. Do you understand how it works? Do you know how to repair it? If not, you’re basically renting it.’ Owning things means taking charge of problems – not making them someone else’s responsibility.

— Veerappan Swaminathan

Finding purpose and process

The story of how an engineer became a choreographer of cultural change tells much about his conviction to elevate human agency. Swaminathan’s trajectory can be traced back to 2006, when he was still an engineering student at the National University of Singapore.

Back then, he worked collaboratively on a year-long, award-winning project in Maharashtra, India, focusing on the prevention of suicide among farmers affected by post-harvest losses. He and his team developed a way to increase the shelf life of produce through solar drying, which could in turn improve the economic situation for farmers.

Subsequently, he was exposed to concepts such as futures thinking, permaculture, and systems thinking. “These insights made the idea of working specifically in sustainability self-evident,” he recalls.

Back home, volunteering experiences with non-profit society Ground-Up Initiative (which focuses on connectedness with nature and sustainable lifestyles) generated another key turning point for Swaminathan. There, his understanding of the great potential of community-driven approaches was shaped, as he experienced effective engagement processes and great outcomes.

After graduating, he pivoted away from the typical engineering path and set up the Sustainable Living Lab (also known as SL2) in 2011. Locally and internationally, SL2 helps clients in the public, private, and people sectors to adopt more sustainable practices using technology and community-driven implementation. Swaminathan has been its Director since day one, and Repair Kopitiam is an offshoot.

In 2016, he established Edm8ker, which supports maker-based education experiences in schools. As CEO and Director, Swaminathan’s goal is to enable purposeful learning that will seed creativity, curiosity, and innovation – essentially, a changemaker mindset. With Edm8ker’s focus on the young, and the popularity of Repair Kopitiam coaching roles among seniors, he is smartly engaging an incredibly broad swathe of the population.

I’ve been very closely associated with the maker movement because I think it’s important for people to learn how to design and make their own things. Repair Kopitiam is a natural extension of that.

— Veerappan Swaminathan

Designing a system and a movement

In the early days of Repair Kopitiam, before demand ramped up, the co-founders ran the repair clinics themselves. These days, Swaminathan focuses on directing operations. He has designed a model that optimises available resources while simultaneously fostering the community that keeps this free service running and sought-after.

From the outset, he could see that the Dutch Repair Café model, in which skilled individuals meet up to assist each other at a low cost, would face some barriers in Singapore. There is a relatively small number of people here with basic repair skills and knowledge – a side-effect of the nation’s economic shift from manufacturing to services since the 1980s. Swaminathan also puts it down to a deprioritisation of skilled manual work in Singapore’s affluent and services-oriented society, and the lack of space to tinker.

“Today, we have high-end manufacturing related to biomedical sciences and so on, but not so much in the electromechanical field,” he observes. This has left some people who once worked in engineering or manufacturing with itchy fingers to apply their skills. Unsurprisingly, therefore, around 60 per cent of Repair Kopitiam’s coaches are seniors. Among budding coaches of a younger age, who lack these skills, Swaminathan has noted that the strongest driver for participation is sustainability.

It was clear to Swaminathan that here, training would have to be part of the model to ensure a pipeline of repair coaches to assist the public. Furthermore, in Singapore, where, as he says, “everything costs money,” careful financing would be a more significant piece of the puzzle than it is in the Netherlands.

His solution is self-sustaining. SL2 covers the labour costs for trainers and the honorariums for coaches. Training courses are provided not only for would-be coaches, but also for members of the public who are keen to pick up repair skills in areas such as electrical repairs, home maintenance, plumbing and drywalling, and furniture and fabric repair. Around 800 people participated in such courses in 2023. There are even courses on basic digital 3D design and mental wellbeing for successful ageing.

Grants and donations (including in-kind goods) supplement the funds injected by SL2, and course fees (which are subsidised for over-50s by the government’s SkillsFuture initiative also contribute to coffers.

From the human perspective, Swaminathan orchestrates Repair Kopitiam activities in a way that purposely fosters a sense of community. Coaches’ efforts are recognised formally with an apron-giving ceremony for each graduating class, long-service awards, and annual gatherings. But more informally, the Repair Kopitiam approach nurtures self-sustaining social bonds.

We encourage collaborative friendships among the coaches. The reason why people join is not the reason why they stay.

— Veerappan Swaminathan

“We try to form a learning community,” he says, adding that meeting weekly and having group lunches as part of the coach training helps with forging connections. The sense of community is also built online, with WhatsApp providing a platform where sharing knowledge among the coaching group becomes normalised. “In Singapore, people normally don’t have that habit of sharing knowledge,” says Swaminathan, “so we orchestrate it a bit to get everyone to contribute.”

The approach is yielding tangible results, suggests Danny Lim, who is Community Innovator at SL2 and a member of the Repair Kopitiam training team. “You will often hear coaches sharing their knowledge and experiences,” he says, “comparing their successes and failures. Some also gather outside our regular meetups.”

Coaches have also demonstrated a strengthening incentive for problem solving, developing their own workarounds for circuitry problems, creating inventory and booking systems, and publishing wikis for common repairs. One thing that has no place in the Repair Kopitiam community, however, is inflated egos.

The shifu (master) culture goes against the open learning, sharing, community model we’re trying to generate. No one can know everything about repair, so a good dose of humility is always required.

— Veerappan Swaminathan

The courage to make positive change

Another sure sign of the strength of the culture that Repair Kopitiam is developing among coaches is the fact that some will turn up for clinics without having been rostered to do so, even bringing their own tools. It’s an admirable level of personal investment in helping the public and sharing their skills.

As for the development of a stronger public sentiment for sustainable living, Swaminathan takes heart in the observations of town council cleaners, who, ironically, have told him about the huge influx of e-waste items being sent for disposal on Mondays after Repair Kopitiam clinics.

“This shows that people are waiting to get their items diagnosed before they discard them,” he says. He continues, “It indicates there’s a general awareness of the importance of not just trashing things but figuring out how to expand their lifespans.” If only more of the items had been designed for repairability!

Swaminathan and the Repair Kopitiam team are not currently tracking any shift in people’s mindsets about how they make their consumption choices, but they are establishing a repairability index for commercially available items. “This is a potentially contentious project, but I look forward to the controversy!” says Swaminathan, showing his characteristic courage for making positive change.

One thing’s for sure: If Han Solo and Chewbacca had found their repair efforts on the Millennium Falcon thwarted by one-way clips, ultrasonic welding, and security screws, their lives could have been on the line. An unrepairable television isn’t going to kill us, but it’s not going to do the planet any good.

We always tell our coaches, ‘You’re not going to do repairs for the public; you’re going to coach the public to do their own repairs. You repair with them, not for them. That’s how you break the cycle.

— Veerappan Swaminathan

1 There is a total of 11 locations for the repair clinics as of November 2024.