Tokyo Translated: observations of a Singaporean designer studying in Japan

Shannon Teoh is the first DesignSingapore Council scholar to pursue an eastern philosophy and approach to design. A top graduate of his cohort for the Visual Communications and Media Course at the Singapore Polytechnic, Shannon’s fascination for design in East Asia was sparked by a visit to the Shanghai World Expo in 2010. Today, he is pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Integrated Design at Tama Art University in Japan. He shares his observations of Japan 12 months after starting school in 2019.

2019 marked the first year of a new era in Japan–Reiwa(令和), as a new emperor ascended the throne. I had the privilege of starting school in Tama Art University, a renowned art institution in Tokyo, in line with the era change.

Tama is one of the most well-known art institutes in Tokyo. Together with Musashino Art University, Joshibi College of Art and Design, Tokyo Zokei University and Nihon University College of Art, it is known as one of the “Tokyo Go-Bi-Dai” (東京五美大), which translates to “Tokyo’s Top Five Design Universities.”

Tama Art University is also the alma mater of fashion designer Issey Miyake, graphic designer Kashiwa Sato and industrial designer Naoto Fukasawa, whom I have long been a fan of. Therefore, as a student studying entirely in the Japanese language in this school, I can say that I have had the privilege of experiencing an authentic side of Japanese design education.

In neighbourhoods where you least expect it, you will find nurseries, bookstores, restaurants, aquarium shops and even zakka stores (雑貨屋 in Japan) bearing proper brand identity designs.

Tokyo is an extremely vibrant city, especially in terms of design. When I first moved over, I was fascinated about so many things. The differences are so distinct. Details that would be obvious to a normal Japanese would be completely unique to me.

Design is everywhere

A striking difference is that they would take design to a more local level. In neighbourhoods where you least expect it, you will find nurseries, bookstores, restaurants, aquarium shops and even mamak shops (Singlish for “sundry” stores, also known as zakka stores or 雑貨屋 in Japan) bearing proper brand identity designs.

These are not franchisees but are owned by humble folks in places with no tourists. A family restaurant of an old couple selling Japanese set meals would have beautiful vintage interiors and music from the sixties. Their attention to detail was most apparent when I noticed their own logos printed on their serviettes and chopstick sleeves.

Zakka shops would have some of the owners’ personal touch – it could be the arrangement or choice of products. For example, they might have an interesting hand cream brand that they brought in from Poland – making it their own curated space. I find an incredibly high sense of pride and even romance towards owning small shops.

In a well-hidden corner, you might find a parlour that sells visually interesting ice-cream sodas or you might find a local bathhouse with the coolest wall paintings. It is rather refreshing and inspiring to take a walk in a neighbourhood that reveals so many tiny universes.

Even though there are many nice hangouts in Singapore – many of which I have frequented – it is not the norm for people of my generation to be managing independent neighbourhood shops like those I have come across in Japan.

If we have a stronger culture of taking pride in our local places, such as adding design value to them, our neighbourhoods would be so much more vibrant.

Another observation is that in Europe, the ancient coat-of-arms emblems that usually appear on flags are typically reserved for nobles. However, the ancient Japanese counterpart, known as the Kamon (家紋), are used even by normal families. In fact, my classmates say that most Japanese families today still have their own Kamon.

Japan is also one of the only countries where even the middle-class employs architects for their landed properties. Therefore, there are cases everywhere in Japan where the general public enjoy good design. This will also lead to an abundance of opportunities for young designers to hone their skills.

A startling observation I had when I first started school here in Japan was that the students demonstrated an exceptional understanding and preference in design.

Most of the students in my current cohort have clear convictions from the start. My peers came to school already familiar with design history, from Bauhaus to Arts & Crafts movement, and having their favourite designer or studio. I think this has to do with being cultivated in an environment where design is celebrated even among non-designers or laypersons.

Japan’s design education

The course that I am studying in is relatively new; it is called Integrated Design. This course was established in 2014 by one of Japan’s most famous industrial designer Naoto Fukasawa. (Google his name and you would realise that you might have touched and used some of the products he has designed for Muji, such as the CD player and the oak bench.)

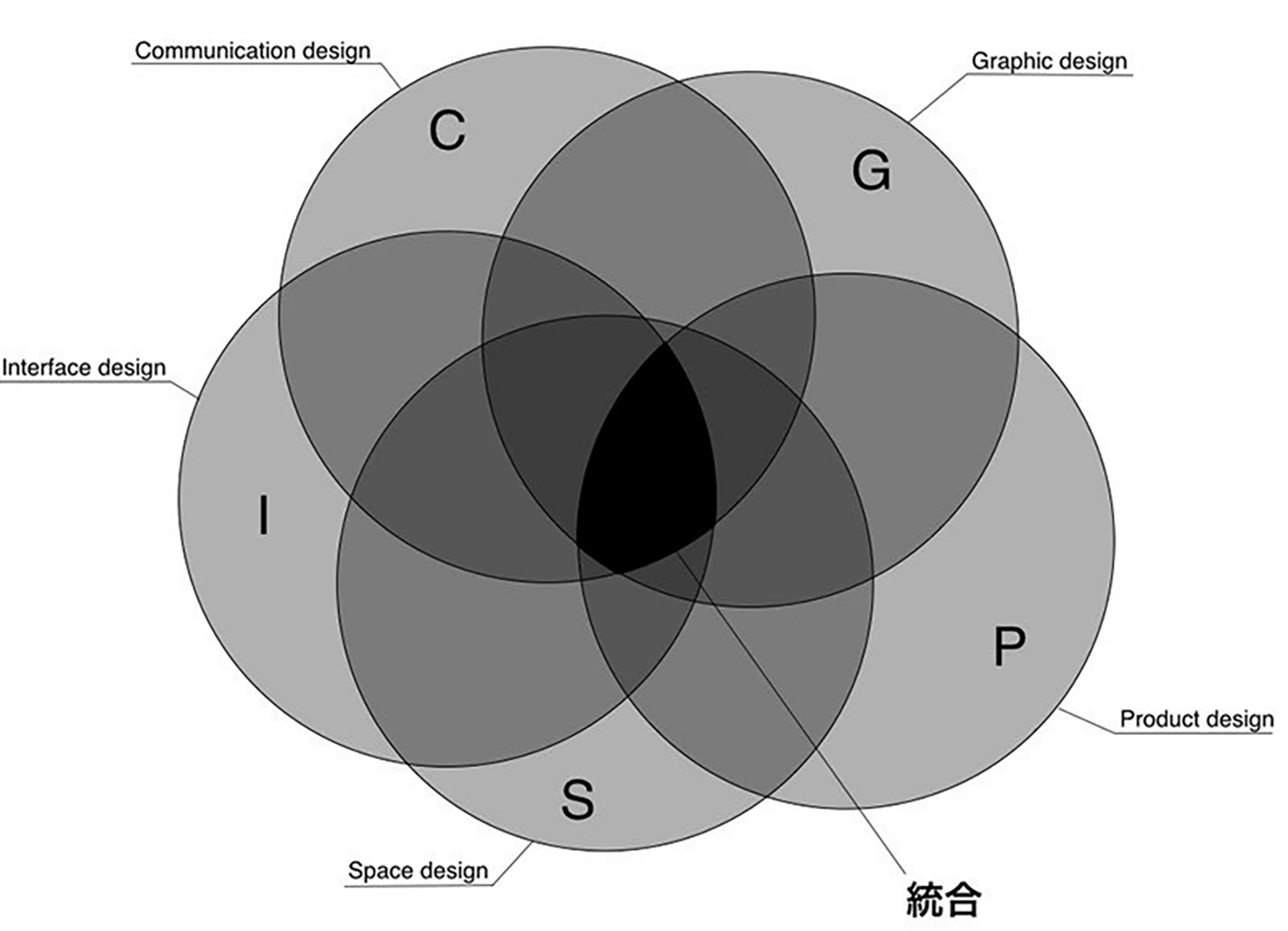

Integrated Design brings graphic, product, spatial, interface and communication design together. A typical week would see us sanding product design models one day and illustrating symbols the next. A way to describe the philosophy of the course is that when you enter a café you would come across many different touch points – the cup, the promotions outside, the interiors, the furniture or even the mobile application. They might all be designed and manufactured separately but they still exist in the same realm. They are all integrated.

Therefore, designing things in consideration with everything else in the surrounding environment is the spirit of Integrated Design. A senior of mine put it in an interesting way when he said: “100 years after the birth of Bauhaus, Design is integrated again.”

The Bauhaus design school was founded upon the idea of creating a Gesamtkunstwerk (“‘total’ work of art”) in which all the arts, including architecture, would eventually be brought together. To unify art, craft and technology, the school had an integrated curriculum where people of different design disciplines took the same foundation classes. My course integrates design education very much like the Bauhaus.

My product design teacher Mr. Watanabe once said to me: “Design is an expression of a nation’s power. Design is culture.” Japan as a nation appears to me as being much more mature in terms of design. Because they have so much design in everyday circumstances, they naturally give the impression that their people are cultured.

I am thankful for DesignSingapore’s support for giving me the chance to learn in this corner of the world. I spend every day here discovering something new about both Japan and Singapore and I hope to someday find something unique that can contribute to the future of the local design scene.

For more information on DesignSingapore Scholarship, visit the DesignSingapore Scholarship page.