Undoing Boundaries to unlock Design Magic

This year’s Singapore Design Week will once again feature SingaPlural, which is organised by the Singapore Furniture Industries Council. This year’s edition, themed Unnatural Phenomena, explores the origins and evolutions of novel new design species, forged by unorthodox collaborations that challenge disciplinary boundaries. Helming the Master Lectures are three such hybrids who have pushed themselves beyond their primary disciplines to explore new grounds. Brandon Kruysman, Elena Manferdini and Raffi Lehrer talk to Pamela Ho about their work.

Photo courtesy of Raffi Lehrer

If you were at the 2018 Coachella Valley Music and Arts festival, you would not have missed the monumental installations created by an interdisciplinary and eclectic team of visual artists, designers and creatives.

The man behind Coachella’s “go big or go home” art offerings was Los Angeles-based Raffi Lehrer. The Associate Art Director for Goldenvoice, with a background in sculpture and furniture design, likes pushing the boundaries on how art is experienced in non-traditional contexts.

The porous boundary between art and design raises no cognitive dissonance for Lehrer – “I’m not interested in patrolling the border of art and design”.

More important to him is how these works and the public engage each other in today’s dynamic contexts. For example, the larger-than-life scale of the installations at Coachella is imperative for a festival for 100,000 people. “They (the installations) are gathering places that give festivalgoers a place of respite, landmarks that aid in way-finding, icons of a specific year that aid in distinguishing our festival from any other festival, and any other year, of Coachella.”

Lehrer also believes in the impact of art/design in transforming communities. He recently worked on bringing Edoardo Tresoldi’s wire mesh sculptures from their 2018 festival to a park in the city of Coachella. “It’s a poor community that’s deserving and in need of beauty. It’s already apparent how this 50-foot architecture-inspired sculpture will serve as a landmark and anchor for the city.”

Hybrids are the new norm

The meshing and blending of disciplines is what makes design today more exciting than ever, says Brandon Kruysman, Creative Technology Director at San Francisco-based design studio, Novel. “The boundaries have gotten much larger. Beyond our traditional responsibilities, designers have been tasked with solving complex technological and social problems.”

He observes a fluidity in working across disciplines now that wasn’t common when he was in school. “Architects or designers fluent in coding were rare then, but now it seems like the new normal. The profession has shown, over the years, that there is value beyond just ‘stylisation’ and that designers can really make an impact in other areas such as research, strategy, and engineering.”

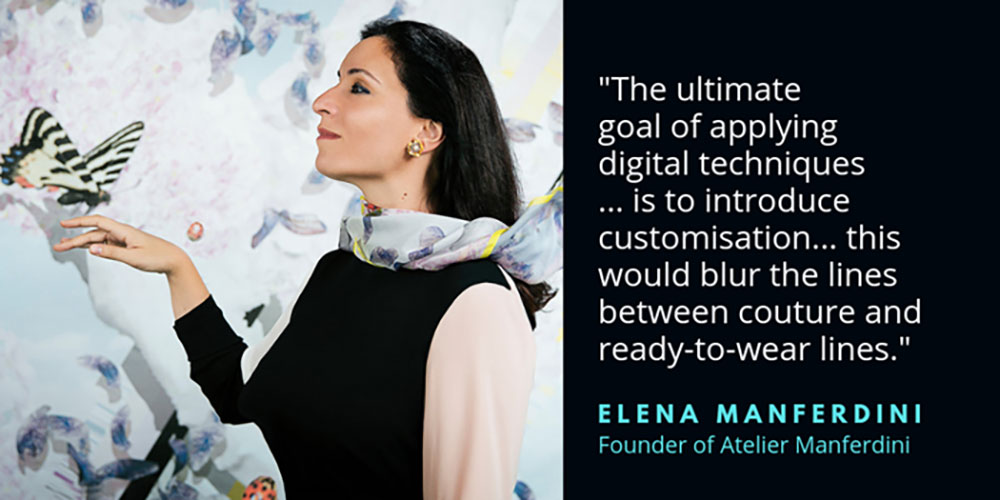

Elena Manferdini, principal and owner of Atelier Manferdini, shares similar observations. With over 15 years’ experience in architecture, art, design and education, the California-based creative says that because digital tools have become the new normal, “designers, fabricators and builders are all on the same digital platforms, and this has enabled a higher level of sophistication in design production and also new collaborative possibilities.”

No idea how but let’s do it anyway

For Kruysman, a Masters graduate from the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), his current work as a creative technologist leverages his background in computational design, digital fabrication and multi-media visuals to translate his ideas to innovative creations across mediums.

Photo courtesy of Bot & Dolly

Photo courtesy of Bot & Dolly

These include an animation-driven robot control system to automate and synchronise camera, lighting, props and actors so that they seem to float weightlessly in space for the Warner Brothers film Gravity, which starred Sandra Bullock. These shots were impossible to be shot using traditional wire work.

“As a communication tool, film has the ability to extend ideas through storytelling,” says Kruysman of the medium. “Just like the act of model-making has a unique way of influencing how you think about space in architecture, creating films has a way of making sense of complex design problems. Approaching the same problem through different mediums can be very insightful and has allowed me to explore ideas from a different perspective.”

Watch the “Mixed Mediums” film of an augmented gallery that Novel designed, developed and fabricated to help app developers understand how they use a new Augmented Images API.

Kruysman’s earliest foray into trans-disciplinary pollination was at SCI-Arc, while working on a thesis on collaborative robotics with two team-mates. “We had no idea what we were doing technically at the time,” he admits. “But each of us had complementary skill sets – coding, motion graphics and digital fabrication – and a real passion to hack machines in the hopes of producing new ways to think about architecture.”

With no space available – and no knowledge of robotics programming – the trio cleared out a closet and spent the whole semester holed up trying to devise new ways of programming robots. Their search led them to an interface developed inside of Autodesk Maya (a 3D computer graphics application) that allowed non-engineers to animate robots without the need of programming know-how, and that became the platform used by the entire school.

From façades to fabric and fashion

Like Kruysman, Manferdini’s multi-disciplinary background has helped turn her ideas into an eclectic body of award-winning works. After graduating from the University of Civil Engineering in Bologna, and receiving her Master of Architecture and Urban Design from the University of California Los Angeles, she founded Atelier Manferdini in 2014. Their recent projects include an eight-storey façade for the Hermitage parking structure in Florida and the gate for La Peer Hotel in West Hollywood.

But the multi-hyphenate is also a fashion designer. “I started crossing the fields of fashion and architecture at the beginning of my career. After a decade of training as an engineer and architect, I approached the problem of the dress as if it were cladding for a building,” she reveals.

“The only tool I mastered at that time was the computer; the only tolerances [permissible limit of variation in materials] I knew were of steel. Form and effect took place only through my understanding of geometry.”

In architecture, almost everything is designed and solved digitally or through scaled models ahead of time. Manferdini credits these skills of visualisation and form-making for helping her enter the fashion design industry. Her Eureka moment came when she realised that computers – as tools for creativity – were able to aid various design fields and therefore allow architects to work across them.

Photos (clockwise from top): Atelier Manferdini, Affluency, HighStreet Culture

Modern technology and machines have enabled customisation in the design and production phases for any field they are applied to – even fashion. “Three-dimensional scanning technology, animation software, and laser-cutting set-ups have enabled us to design for a specific human body and produce a one-of–a-kind, mass-produced garment,” she elaborates. “The ultimate goal of applying digital techniques to fashion is to introduce customisation in the design phase. In the long run, this would blur the lines between couture and ready-to-wear lines.”

Manferdini, whose hybrid knowledge has birthed a unique practice, says multi-disciplinary and multi-scale design can promote an integrated, all-encompassing view of reality. Kruysman agrees that looking at the world through different lenses is “the only way to get a clearer and more holistic understanding of a complex problem”.

“For me, the magic is in building teams with hybrids – like engineers with a deep appreciation for design or designers with the ability to code. This creates a team that is as much creative as technical, and thinks differently about solving problems.”