Low Cheaw Hwei Envisions a Singapore Where Creative Thinking is Second Nature

After a three-decade design career in which he contributed to Singapore’s evolution from a manufacturing to service-based economy, Low Cheaw Hwei is now embarking on a new chapter of design consultancy and pushing the agenda of design through setting up a design think tank. It is an ideal complement to his advocacy work in pushing for the embedding of design into Singapore’s education system. He believes our future depends on the creative and innovative thinking that design nurtures.

Article by Justin Zhuang.

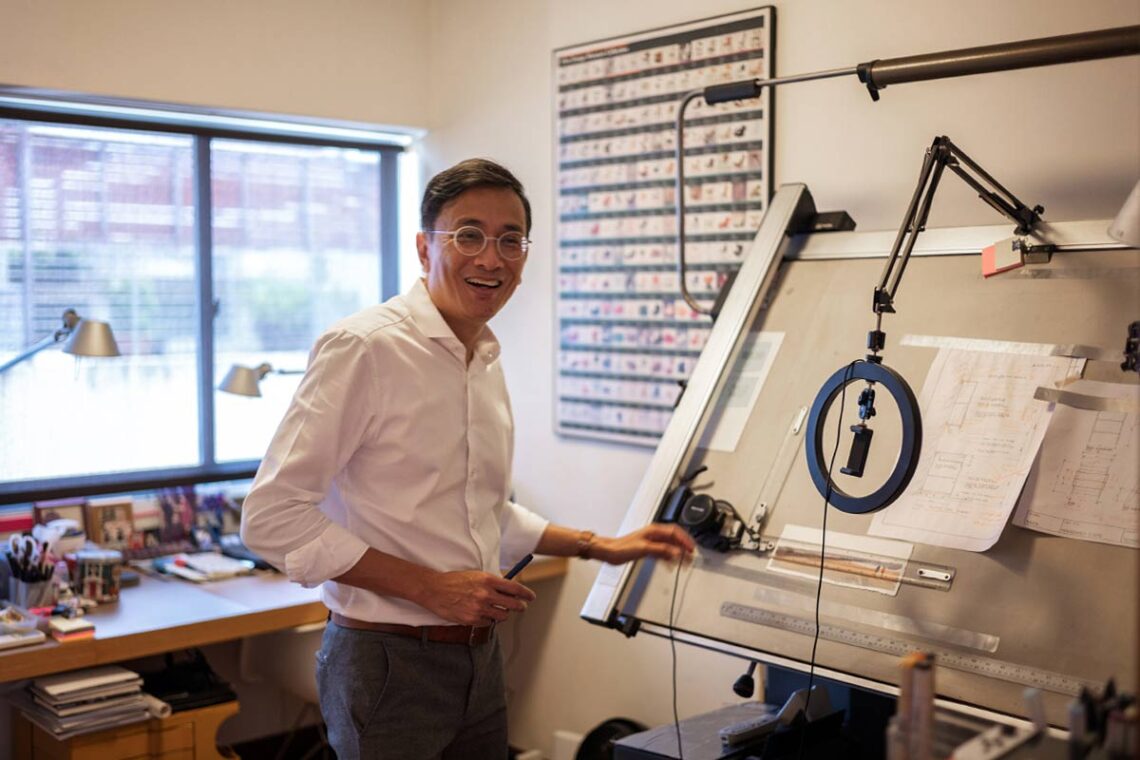

If you’ve ever used an electric toothbrush, television, home appliance, or healthcare device from Philips, chances are you were using a design that Low Cheaw Hwei had a hand in creating. He worked for the Dutch multinational conglomerate as an industrial designer for over three decades, starting out in its Singapore office in 1991 and steadily rising through the ranks to become Philips Design’s Chief Design Officer for television and audio-visual multimedia products as well as Global Head of Product and Service Design for Philips’ entire product portfolio. He eventually oversaw design for the company’s operations across the ASEAN Pacific region, which included not only products but also experiences, services, spaces, and even strategies.

In many ways, Low’s storied career embodies Singapore’s efforts to grow the nation’s industrial design capabilities. He was part of the first batch of students who attended Baharuddin Vocational Institute’s (BVI’s) product design course, which the government launched in 1989 to nurture a local design workforce that could help industries here manufacture higher-value ‘made in Singapore’ goods for export. This was why Philips hired Low in 1991. At that time, the company, which had established manufacturing operations here in the 1960s, was expanding into designing its products locally for the global market, too.

As the Singapore and global economies evolved over the decades, so did Philips, the local design industry, and Low. Philips ventured from consumer electronics into consultancy to tap into the growing services industry, and Low was part of this transformation. He expanded the role of his design team to help Philips become the health technology innovator it is known as today.

An accidental designer

The need for design to ride these economic shifts and industry trends, however, was far from Low’s mind early in his career. He became an industrial designer somewhat by accident. As he had always enjoyed drawing, a young Low was influenced by his sister’s stint in the graphic design course at BVI and his brother’s architecture study at the National University of Singapore. He applied to study graphic design at BVI. At that time, there were no local universities that offered design courses, aside from architecture. To his surprise, however, he failed to make the cut.

“I was quite upset and disappointed. Then they said, ‘We have this new product design course, would you like to try?’” recalls Low. “My plan was to get into Baharuddin first, and then make an appeal to switch courses.”

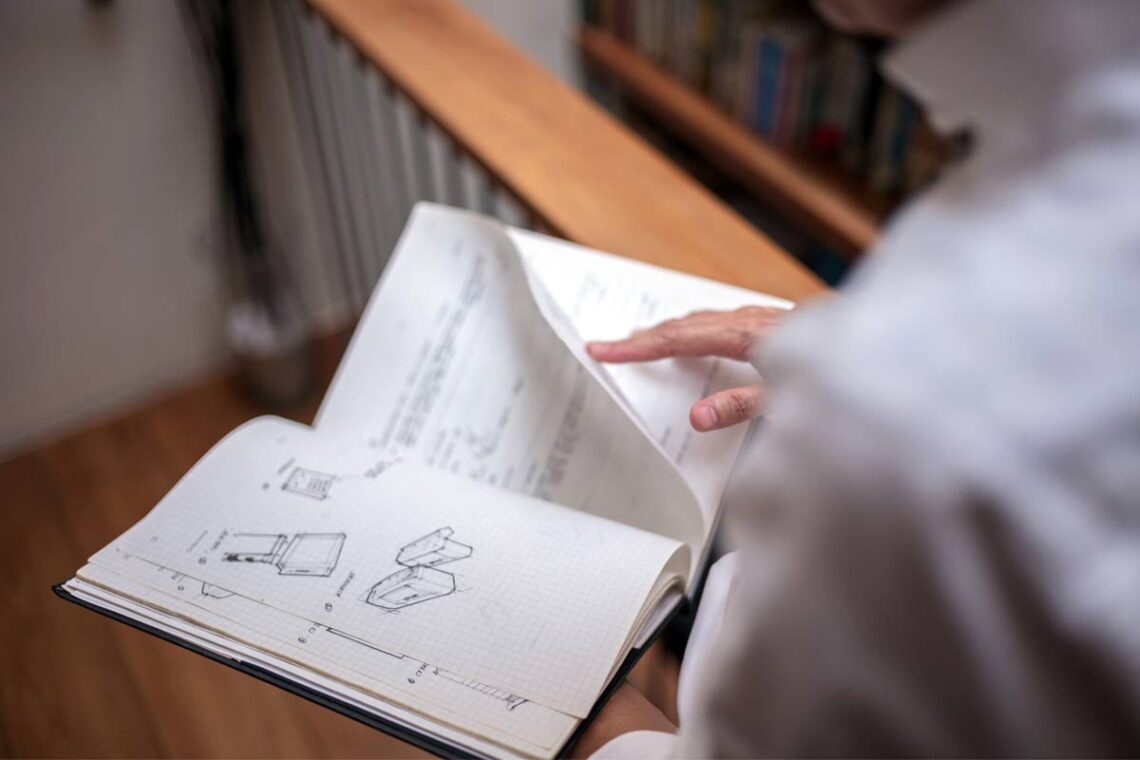

He never did. The experiential learning approach of course manager Frank Drake helped Low fall in love with product design. Students were asked to build models of a Malay house to understand craft, scale, structure, and culture. They learnt engineering principles by designing floatation devices that were tested at the nearby Queenstown swimming pool. During class, films such as Brazil, Mononcle, and Star Wars were screened to teach students the “language and cultural context of objects” and how design was shaped by the larger environment.

“I started to see design from a very, very wide perspective, including culture, politics, and philosophy. That was a confusing and enriching time. We were mentally thrown in the deep end. We got to do things with our hands, and I realised how much I enjoyed building and crafting things,” says Low.

Measuring up with the world

He eventually excelled in the course and received a scholarship in his final year to attend a summer studies programme at the prestigious Domus Academy in Milan. Upon returning and graduating from Temasek Polytechnic (BVI design courses having been elevated to diploma level in 1991), Low joined Philips and was soon assigned to its headquarters in Eindhoven – specifically to the audio concept design team.

The experience of working overseas for the first time was rewarding, but more importantly, it was assuring for the young designer. Working alongside his colleagues in a multinational team, Low realised that Singapore designers could measure up with the rest of the world. “Before that, I had always been asking Frank, ‘How good are Singapore design students?’ I was very concerned with this,” he says.

Within two years, Low was promoted and transferred to Philips’ office in Hong Kong to take on the new role of translating design concepts into actual products. During his four-year tenure, he helped Philips’ audio products better compete against popular Japanese brands. He saw up close how design gave businesses a competitive advantage, especially for commoditised consumer electronic products, such as clock radios, cassette players, mini hi-fi systems, and portable CD players.

To ensure his designs worked in the market, Low also travelled with business development colleagues to present upcoming products to retailers. Such design-led business engagement and research helped him receive feedback directly from buyers and learn what the competition was up to. He realised that design considerations had to be applied at the point of product conception to have a better chance of success.

If you really want to flex the muscles of design, a designer must be involved in all areas of the business. I definitely do not accept the notion that design is at the tail end of a product’s development and designers have to perform magic. It starts with design!

— Low Cheaw Hwei

Paying it forward back home

In 1997, Low returned to the Singapore office. His role in Philips continued growing and he soon became the Chief Design Officer for audio and television products globally. Despite his busy schedule, Low found time to contribute to the ongoing transformation of Singapore’s design industry. In 2003, the DesignSingapore Council (Dsg) was established to grow the creative industries. Low served as a member of the Dsg Board from 2005 to 2011, and witnessed the early efforts led by former Dsg Executive Director Dr Milton Tan to put Singapore on the world design map.

In 2009, Low played an important role as the Chair of the Congress Organising Committee that brought the International Council of Societies of Industrial Designers (Icsid) World Design Congress to Singapore. This, recalls Low, was an event regarded by many in the industry as the “Olympics of design”. He worked closely with Icsid and Dsg in the Committee to shape a lively programme of presentations and on-site studios focused on the difference design can bring, and the possible futures design could enable.

Having benefitted from the vision of the likes of Mr Tay Eng Soon, the Minister who introduced design as a course of study in Singapore, you can say I am paying it forward.

— Low Cheaw Hwei

More recently, he has turned his attention to reshaping education by design, to ensure Singaporeans have the skills and capabilities to thrive in the future. This is why he accepted the offer to chair the inaugural Design Education Advisory Committee (DEAC), the first-ever national platform for design education thought and practice leadership launched by Dsg in 2020.

The committee – comprising leaders from institutes of higher learning (IHLs), the design industry, non-design sectors, as well as government policymakers – has been meeting quarterly to explore ways to raise the quality of design education and embed design into Singapore’s education system. Over the first two-year term, the DEAC outlined six pillars that form a “Point-of-Vision” for the future of design education in Singapore as well as 11 ideas on how to realise this.

Among them is encouraging more research into, through, and for design, which Low strongly believes in. While serving as DEAC Chairman, he has also supported Dsg’s Good Design Research (GDR) initiative as a mentor and evaluator. “GDR is a very good Dsg programme and I’ve been delighted by the diversity of thinking and the variety of teams pitching,” he says.

For the longest time, design has been perceived as a subjective topic. For design to be taken more seriously and to thrive, the discipline must create our own set of domain knowledge.

— Low Cheaw Hwei

The future of design and education

Low and the DEAC have spent their second term elaborating on what design education could look like as well as expanding the other pillars and prototyping ideas. When the committee’s full report is launched next year, Low believes it will offer IHLs and anyone interested in design education a range of new and inspiring directions to pursue.

Beyond helping design educators prepare for the future, Low is also keen to embed design in the general education system. He says that while Singapore has done well in training people for an industrial economy over the last five decades, things are less straightforward now as the nation transforms into one that is driven by innovation.

“While future job scopes may be vague, it is clear that we will need a lot of fundamental capabilities and skills in creative thinking. Are schools still training disciplines to fill specific roles, or are they inculcating capabilities so students can take on a diversity of opportunities out there?” Low asks.

It is not just about training people to practise design, but also to have the skill of design as a creative problem-solving capability. In order to do that, the shape of education has to change.

— Low Cheaw Hwei

Society’s understanding of what creativity is must evolve too, he adds. As a speaker at Dsg’s upcoming Design Education Summit, Low will make a case that creativity is not just about having relevant cognitive skills; more fundamentally, it is also about the adoption of certain behavioural traits applicable not just in the creative fields but also our everyday lives.

“When I was younger, many people linked creativity to something that was on the fringe. My mother would describe me as gu ling jing guai (quirky and weird),” he says, by way of example. “I like to address creativity from a cultural point of view – as something very normal that we see every day.”

Singapore design is ready for the world

In July this year, Low closed his chapter at Philips to start a new one as an independent consultant. He is eager to bring his vast experience in consumer product and healthcare design to a variety of new projects and even new domains. He also has plans to establish a think tank for design – a platform for debates, discussions, and discourse that may deepen understanding of the discipline and its potential to drive new perspectives and innovation.

“Design is evolving to be ubiquitous. That is the reason why we need to build a strong intellectual and practice base to provide thought and practice leadership to the economy,” he says.

Low believes Singapore is ready for more design discourse, precisely because of its thriving design industry and many accomplishments. This nation by design has developed a unique take on the discipline. Low has spent his career straddling the East and West, and admires speed of working in the former and the depth of thinking in the latter. He believes Singapore designers can strike a good balance between the two, given the nation’s links with both cultures.

“Singapore should have more confidence in itself in the area of design. We no longer have to reference other countries,” he says. He adds, “We can offer the world our own discoveries about solving problems as a little red dot. We can offer the world a very different flavour and philosophy of design.”

Read our unfolding series of stories on creative discovery and making life in Singapore ‘Better by Design’.