Creating the new building blocks of sustainable architecture

What does the hibiscus plant have to do with sheltered linkways? Studio SKLIM has found a way to use one hibiscus species to create a hardy, innovative and sustainable material that can be used for roofs and walkways. Meet Kenopy, which could change our built environment as you know it.

By Justin Zhuang

The hibiscus is well known for its vibrant and distinctive-looking flowers, but there is more than meets the eye. Several species of the plant, such as the kenaf, are also known for their strong fibres and have been used for decades to produce textiles and rope.

In 2020, designer Kevin Lim started on his Good Design Research project to look into how kenaf could be used to create bio-composites for producing architectural tiles like those used for shelters and roofs. Such construction materials are currently made from non-renewable sources that generate carbon, including timber, steel, ceramics and concrete. Kevin shares how his Kenopy project, a play on “kenaf” and “canopy”, has led to new opportunities and expanded the possibilities for sustainable architecture.

How did Kenopy become your Good Design Research project?

For the past six years, my studio has been working on projects in India where we have been exposed to local green standards, such as examining material sources to reduce a project’s embodied carbon footprint. We have also witnessed cultural practices such as roadside vendors using pressed leaves and pavers made from fly-ash. They have exposed me to considering alternatives to imported building materials, and to tackle the issue of sustainability in construction more proactively.

I was first introduced to kenaf in a previous project with Tim Tan of AffordAble Abodes, who uses them to create panels for building houses. As a natural and renewable resource, I thought kenaf had potential to create a “farm-to-shelter” construction material and wanted to investigate if it was possible to improve on Tim’s work with even lighter and better-performing kenaf panels. We were both stuck in Singapore when the pandemic hit, and I had learnt about the Good Design Research (GDR) initiative. I reconnected with Tim to participate together.

During application, we had to identify a problem our project could solve and that led us to the Land Transport Authority’s masterplan to construct 150 km of sheltered linkways by 2040. That is almost the entire perimeter of Singapore’s coast! We realised that roofing these walkways with a sustainable material like a kenaf bio-composite would make a significant impact on creating a more sustainable built environment.

Tell us more about your research process.

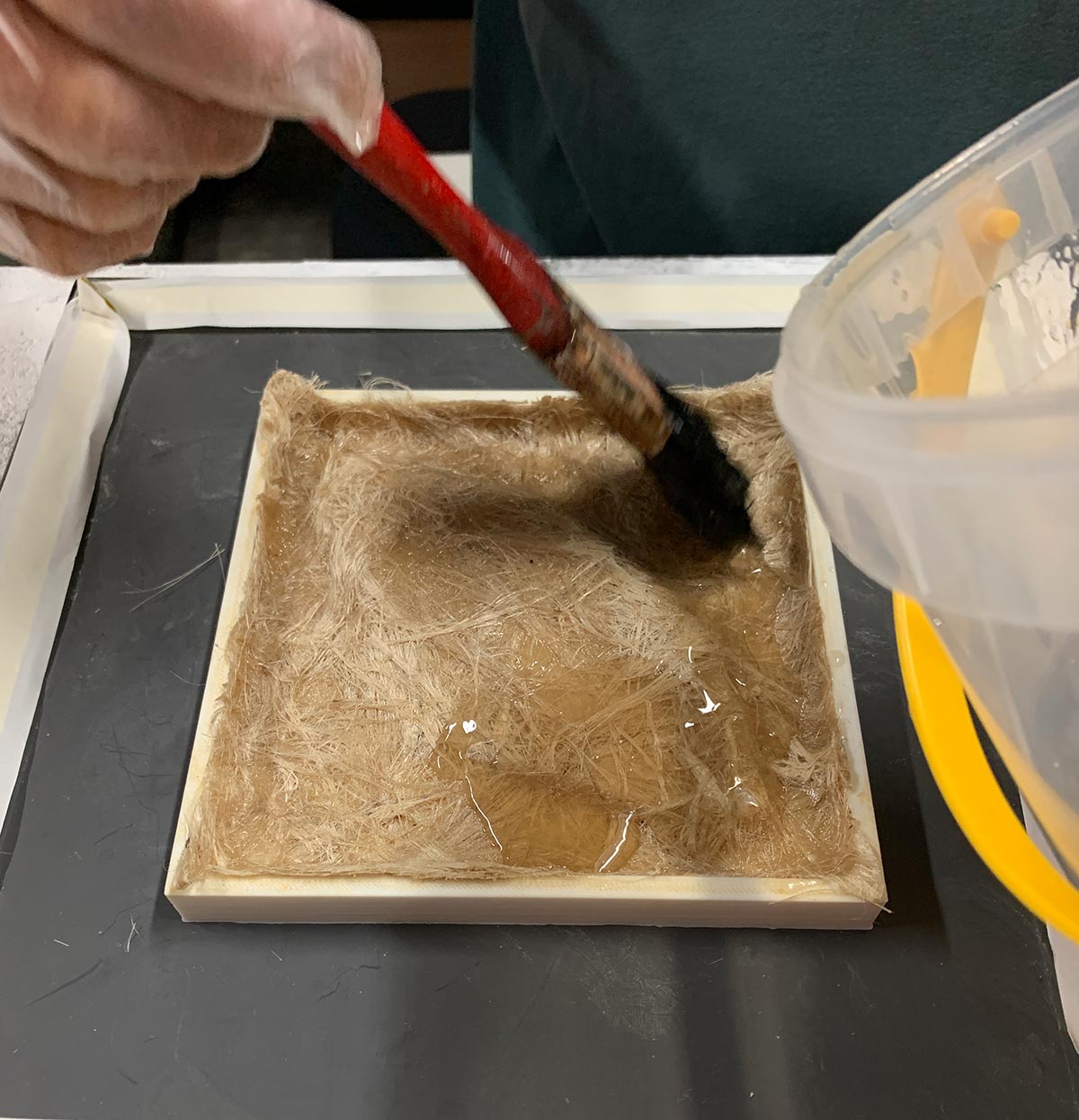

We started by prototyping tiles for the interior and worked our way towards the exterior. The end goal is to create a prototype shelter as a proof-of-concept. Building on Tim’s knowledge, we have been experimenting with various moulds and techniques to create different kenaf tile designs. Along the way, we also introduced organic dyes such as turmeric, beetroot and even blue pea extracts to test if they would penetrate and permanently alter the natural colour of the fibres.

We were fortunate to have Tai Lee Siang as our GDR mentor. As an architect and formerly from the Building and Construction Authority (BCA), he pointed us to industry standards on materials that might be relevant for comparison. Thanks to him we also got to carry out our research in a workshop space at the BCA Academy for a nominal sum.

This is the future of practice, which will involve a more vested interest in material production and innovation. Rather than only being involved in traditional design decisions on a macro scale, we can now influence change at a micro product level too.

What insights and outcome have you gathered?

We have successfully prototyped interior Kenopy tiles, and I even managed to convince a client to use them in his new café, Handcraft Coffee. He could see how our approach of designing with sustainability aligned with his brand and business and through the process of creating the tiles for his café, we discovered that light altered the materiality of the panels and brought out the natural beauty of the fibres. Thus, we created four 900-mm-long panels as light features in the café. The client was very pleased with the outcome and even remarked that we should have created more tiles as they add such dramatic highlights.

What is next for the Kenopy project?

For the final leg of our research, we are creating exterior Kenopy tiles to roof a pavilion and exploring how we can simplify the currently labour-intensive process of creation. Achieving a proof of concept through GDR is just the first stepping stone towards creating an architectural tile for mass production. In the future, we can also explore improving the performance of the tiles with features such as solar panels.

How does it feel to see Kenopy grow from an idea into an actual prototype?

As a designer, my practice has always been interested in craft and experimentation and we previously did so with existing materials such as rattan, bricks and concrete. But instead of just selecting materials and practices, GDR has allowed us to become a design instigator. It cuts short our process of convincing clients to adopt our material choices because we are familiar with our own products and can explore new design boundaries through research and making.

This is the future of practice, which will involve a more vested interest in material production and innovation. Rather than only being involved in traditional design decisions on a macro scale, we can now influence change at a micro product level too. This is perhaps a more holistic response towards a more sustainable built environment.