For Jackson Tan, Design is an Evolving Process of Possibility

Few designers are able to navigate the complex matrix of identity and culture as deftly as Jackson Tan. From branding products to branding a nation, he has created visual identities so crystallising that they become part of culture. Now, he is harnessing the power of design experiences to enable a broader capacity for creativity.

Article by Narelle Yabuka.

Remember SG50? Emblazoning everything from umbrellas to commemorative $10 notes to a Singapore Airlines plane, a succinct red dot with white lettering came to represent Singapore’s 50th year since independence.

It was simple, but therein lay its brilliance. By referencing a moniker with which we were already familiar (Singapore as a little red dot on the world map), it was something that all Singaporeans and Singapore residents could identify with. But did you know that the famous logo – and the very term “SG50” – were created by one of Singapore’s most celebrated design talents?

A logo with impact

Jackson Tan is the award-winning Co-founder and Creative Director of BLACK (a creative agency established in 2003), and Co-founder of PHUNK (an art and design collective established in 1994, and recipient of the President*s Design Award [P*DA]), among other roles. In 2013, he was invited (along with other designers) by the Ministry of Culture, Community, and Youth (MCCY) to submit a concept via BLACK for Singapore’s fiftieth anniversary identity. His design for MCCY couldn’t have been better. So concise was his expression of the nation and its milestone anniversary that it was adopted with no revisions, he recalls. “It was like a dream come true,” says Tan.

The mastery of the red dot icon was matched by the cleverness of the slogan. Tan insightfully recognised that moving forward, our national branding would benefit from a simple acronym – an “SG” that could speak for itself just as “LA” and “NY” do. Inspired by Milton Glaser’s “I heart NY” logo, he paired “SG” with “50”. The next thing he knew, a TV newsreader was declaring that 2015 would be SG50. By taking thinking far beyond the limits of a traditional logo, Tan had created an enduring facet of culture.

Identity as culture

As a specialist in branding, design, and curation, Tan has built up an impressively broad portfolio of identities, exhibitions, visual artworks, and public experiences that have been applied from the scale of single brands to the nation at large – and beyond. Without question, you would have encountered his designs in Singapore. Pivotal to his work through the years has been an interest in developing creative cultures – that is to say, producing designs that generate social, cultural, commercial, artistic, intellectual, and emotional value.

It’s no surprise then that Tan’s career path has been deeply intertwined with the DesignSingapore Council (Dsg) over the years, given the latter’s mission to develop Singapore’s ecosystem and culture of design. With the BLACK team, Tan has created many identities (as well as publication and exhibition designs) for Dsg, including for the P*DA in 2006, Icsid World Design Congress Singapore in 2009, Singapore Design Golden Jubilee Award in 2015, and Dsg Design Conversations in 2019. In fact, one of Dsg’s foundational projects would take an unanticipated but transformational path thanks to Tan’s unique perspective.

In 2004, he was approached by the Council’s founding Executive Director, the late Dr Milton Tan, about an opportunity to promote Singapore design at a leading international design conference that was being held at the Singapore Expo that year. “Dsg had just been formed and Milton didn’t have any collaterals yet,” Tan recalls. “He asked me if we could do a brochure on Singapore designers. I told him people would just throw a brochure in the bin because there was little awareness of, or interest in, Singapore design at that time. I said, ‘Why don’t we do something to catch people’s attention?’”

That was the beginning of a four-year exhibition series titled 20/20 – an exploratory showcase of a ‘perfect vision’ of Singapore creativity across a range of disciplines, from architecture to fashion, photography, graphic design, industrial design, and illustration. As the curator and designer of the exhibitions, Tan orchestrated an open-ended expression of Singapore design and the spirit of the time – inviting the first 20 exhibited creators to nominate the next 20 for the subsequent show, and so on.

In the 1980s, when we were nation building, a lot of design work was service based – servicing multinationals based in Singapore. There was limited scope for national identity or voice. For my generation, and the younger generation, there’s been more room for authorship, and for local identity and culture to be projected. It mirrors Singapore’s rise as a global player and as a place that people understand. Design has very much been part of that.

— Jackson Tan

“Before Dsg, design was primarily tied to trade and defined by industrial design, because Singapore presented itself as a place that manufactured things,” explains Tan. “But we were moving away from that.” In parallel, he recalls, the boundaries between creative disciplines were beginning to blur, and discipline-defined cliques were starting to interact – especially in environments such as Zouk nightclub. “In a way, 20/20 was trying to campaign for that cross-disciplinary interaction,” says Tan, while it also spread the word of an emergent design and creative scene eclipsing traditional definitions.

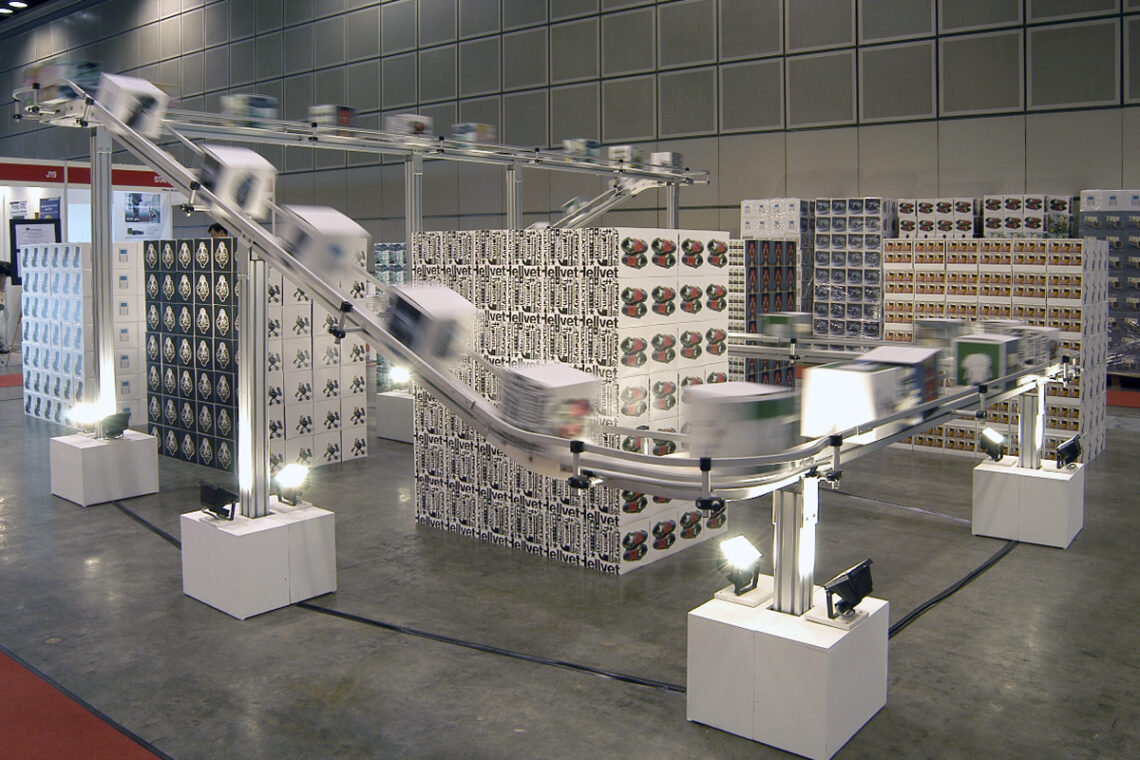

20/20 succeeded in capturing attention and attracting queues. Aside from the fascination of the conveyor-belt design of the 2004 show, which Tan says, “made fun of the idea that we were manufacturing creativity”, visitors were anxious to get their hands on the 2,020 collectible boxes. Every box, printed with exhibited designs and containing an accompanying exhibition booklet, was snapped up by conference-goers. “We sized them so they wouldn’t fit in the bin!” he quips.

Tan had managed to present Singapore design as a form of desirable cultural currency. Singapore was establishing itself as a place to watch on the global design circuit, and Tan was contributing to the emergence of its design culture.

I feel that Singaporean designers are now much more savvy and more connected to the rest of the design community around the world. We have a huge role to play in shaping the future of the world through design.

— Jackson Tan

A culture of enabling better outcomes

Nearly 20 years later, working in the context of a matured design industry, Tan is looking to a broader horizon. His thinking has turned to design’s potential to resonate in a different way – as an enabler of new modes of understanding, better experiences, and problem solving.

For example, his award-winning ART-ZOO brand, created with BLACK in 2017, creates playing, learning, and storytelling experiences for children and families that aim to encourage curiosity, creativity, and empathy. It was launched publicly with a fantastical landscape of giant inflatable creatures at Marina Bay. “I wanted to create the next generation of animal-themed playgrounds for Singapore,” he says in reference to our older public-housing estates.

ART-ZOO has since expanded with a suite of assets for workshops and stories. Dsg’s Good Design Research initiative supported the development of ART-ZOO’s touchpoints and educational framework with grant funding in 2021.

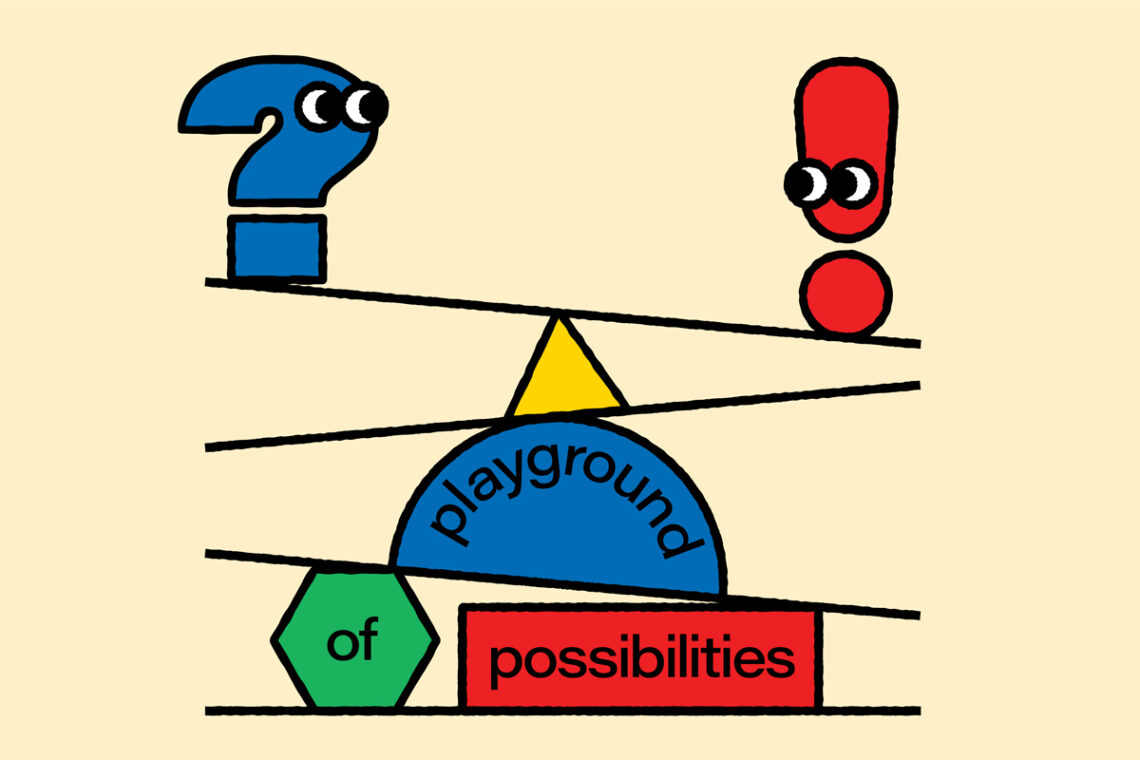

Tan will take his enabling spirit to an even broader audience segment at Singapore Design Week 2023, with a special Dsg-commissioned experiential showcase at the National Design Centre titled Playground of Possibilities. He is presenting a curated selection of design projects from Singapore that tackle some of today’s most pressing challenges and provide inspiring solutions. By contextualising design innovation, and presenting it in a playful way, his aim is to demystify design processes for a non-design-trained audience.

He explains, “With Playground of Possibilities, we’re looking at how design innovation can create possibilities. Problems can be turned into possibilities through design processes. It’s like cooking – not everyone is a chef, but you can pick things up to enable you to cook, and even to enjoy it.”

The show will run until the end of 2023, and without doubt, Tan will be keenly observing how people interact with the displays. “It’s quite an experimental show,” he says. “It’s closer to a design playground than an exhibition,” he adds. Either way, it marks an important ambition for Singapore’s design culture: a broad reverberation and embrace of design’s potential to make life better.

As a design city, Singapore can look at design not just as an industry, but as an enabler. Things can go deeper when the public understand the ‘how’ of design.

— Jackson Tan

Read our unfolding series of stories on creative discovery and making life in Singapore ‘Better by Design’.