End-of-life care needs a reset. Here is how it can be done

By Lekshmy Parameswaran

When I tell people what I do, they sometimes walk away from me in shock or fear. As a designer specialising in the health and care space, my team and I look death and dying in the face, seeking ways to help individuals and their loved ones confront and overcome the challenges that come with the last stages of life.

Unfortunately, people don’t want to talk about it, which makes my job especially challenging.

Let’s face it, death is scary; it is stressful, inauspicious and dark. But it is also significant, intriguing even, and, most importantly, inevitable.

It could affect any of us at any moment, which is why I think it is good to open up a conversation on the subject. But it is often too late when we do so.

What compounds the issue is the fact that Singapore, like many other parts of the world, is grappling with a rapidly ageing population. This is why we need to start talking about death, and now is probably the best time to do so.

The Covid-19 pandemic has upended our lives, causing us to revise practices and redesign rituals, including end-of-life care and funerals. The significant restrictions on visitor numbers, outings and group activities at inpatient hospices, for instance, have prevented patients and their loved ones from spending quality time together on the last leg of their journey. This has resulted in distress for many families who had to turn to phone and video calls to say their final farewells. There have also been tragic cases of patients passing away alone.

Attendance at funerals is also subject to evolving Covid-19 measures. Initially, only immediate family members were allowed to attend the funeral of their loved ones. Although rules have since been relaxed, bereavement will continue to be limited by space, time and communal support to grieve before the pandemic is under control.

Redesigning palliative care

These experiences serve as a stark reminder of the responsibility of designers to reshape the experience of dying. Design can play a significant role in palliative care – a specialised approach to caring for people battling life-threatening illnesses.

In Singapore, palliative care can take place in various settings, from acute hospitals, community hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, hospices and even in a person’s own home – depending on the complexity of care required and available resources, and also individual preferences.

Prior to the pandemic, the 2015 Quality of Death Index by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) ranked Singapore 12th among 80 countries. While faring well in categories of affordability of care, quality of care, and human resources, Singapore performed the weakest in community engagement.

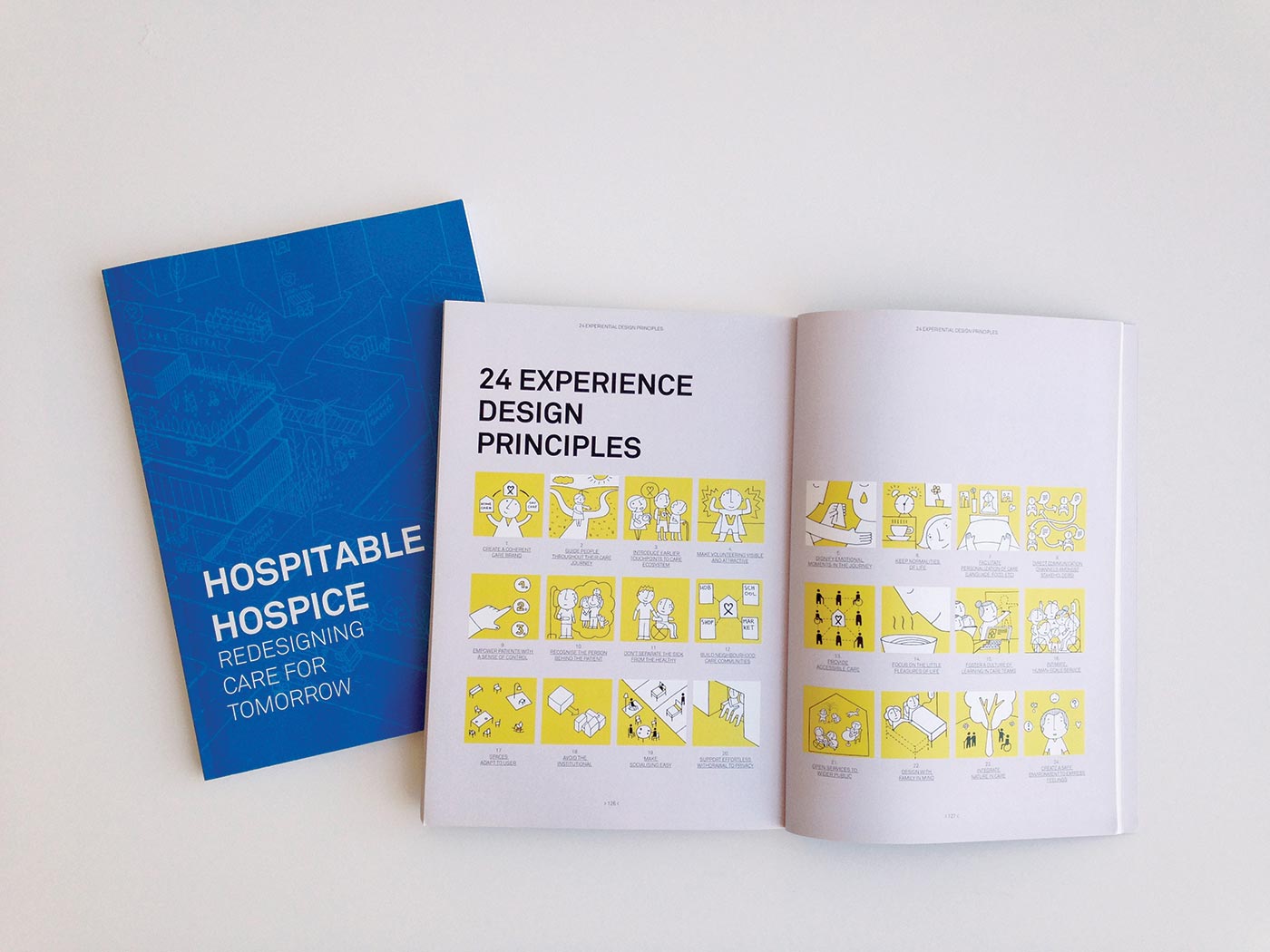

Organisations such as hospices are recognising the issues and working with designers to create more holistic solutions. Our design team at The Care Lab is working with registered charity HCA Hospice Care (Singapore’s largest home hospice care provider), the Lien Foundation and Lekker Architects to create a new day hospice model in Singapore called Oasis@Outram, which will serve patients with life-limiting illnesses.

Besides Oasis@Outram, I was involved in co-creating the service blueprint working with three inpatient hospices in Singapore: St Joseph’s Home, Dover Park Hospice and Assisi Hospice.

The concept of an “open hospice” was a key component of the design strategy, where we broke down the walls and engaged with the local community to shift negative perceptions.

There were also events and programmes jointly organised with the local market, schools and community centres to open up the hospice and normalise the end of life by coming together to celebrate living.

St Joseph’s Home can now be seen as one such community in the Jurong neighbourhood.

While the home continues to offer primary nursing and hospice services, it has facilities that engage different groups of people and build a sense of community. These features include volunteers and residents working together to tend to the vegetable gardens, the home’s family living concept with communal cooking and dining areas and recreational spaces, and even a childcare centre located within the home, encouraging interaction with the elderly.

Another area where design can contribute is in smoothing the transition in services from long-term to end-of-life care, which can be an extremely bumpy and stressful process for patients and their families to navigate.

One approach is by training healthcare practitioners focused on curative care to better communicate with the dying and their families and help prepare them for the end of life.

Positive connections

Design can also help by facilitating conversations around end-of-life care.

Bite Size Future is a conversation toolkit that The Care Lab team developed in partnership with St Joseph’s Home and the Lien Foundation to help find the words to share what someone might be feeling, wishing or fearing at the end of their life.

Essentially, a family member and resident are invited to afternoon tea with a social worker or hospice nurse, where a cookie is paired with a card that contains a question relating to end-of-life choices for the patient.

Oasis@Outram is taking this a step further by having a dedicated Conversation Room decked out with warm, inviting decor and furniture where such conversations using these toolkits can be held.

My team at The Care Lab have also designed service rituals for care professionals to offload their own emotional baggage, so that they have the headspace to hold a good conversation with a family member, resident or patient.

This is delivered as a kind of board game that teams can use in a group workshop to discuss, in a structured manner, their reflections on what happened in the past week or month, sharing the challenges or joys they have experienced.

It helps by normalising the highs and lows of their job, and provides a safe space for stress to be released, and for solidarity and community to flourish.

Death as part of life

Dying is not defined by time, age or disease. I see end-of-life as a distinct life stage, apart from when it is unforeseen, and that explains why I regard it as an experience in and of itself.

The focus of care shifts away from being curative towards the quality of life and the significance of human relationships.

Palliative care professionals and geriatricians are specialists in dealing with end-of-life issues. I have learnt by working alongside them for almost 10 years that it is about listening carefully to what matters for each patient.

That, in itself, is challenging, since in the spirit of filial piety, many families feel obliged to take control and, fuelled by their own natural fears and anxiety, may even take it a step too far in their care, resulting in the patient’s voice and preferences getting drowned out.

Challenges are also found in the physical environments of the institutions looking after people at the end-of-life stage.

While families are encouraged to participate in the caring of their loved ones, facilities are not always equipped with good options for them to stay comfortably.

Residents then often end up in rooms that feel institutional, with poor lighting and little or no personal space – not well-suited to their needs in this final and important life stage.

Not to be neglected either are the caregivers – the close friends and family members – delivering day-to-day care, who can be “hidden patients” themselves given the adverse mental and physical consequences they face from demanding caregiving work on top of their existing work, financial and family responsibilities.

Interventions designed to help the caregiver become more competent and confident are essential to ensure that their loved one receives loving, safe and consistent care. For instance, a caregiver in a positive state of mind and equipped with the right practical skills can identify problems for their loved one before they turn into a crisis, better alleviate their fears and frustrations and become advocates for their end-of-life wishes, as well as being able to practise self-care and avoid their own caregiver burnout.

End-of-life care should be positioned in the same way that we celebrate and support newborn babies and their parents – with compassion, a strong focus on the person and their family, and free of societal taboos. For instance, we announce our births in our communities with unabashed pride and joy, and that is an approach we can seek to emulate when speaking about our preferences at the end of life.

Good design can contribute significantly to this reset. I believe it can help us all to reframe this life stage to be experienced as a personal moment of reflection and peace for the individual and everyone involved; to remember, honour and celebrate a life lived.

If our relationship with death and dying can be repositioned to be one of positivity despite the pain, it can provide us with an even greater appreciation of life, while instilling a sense of calm about a subject so fundamental to our existence.

I share this idea at every available opportunity, as part of the reset we are trying to redesign with end-of-life care in Singapore and beyond.

When people stop walking away from me when I tell them what I do, then I know we may just have succeeded.

Lekshmy Parameswaran is co-founder of The Care Lab, a design practice based in Barcelona, working internationally to transform systems of care. She received the Design of the Year accolade at the 2018 President*s Design Award (P*DA)

This article first appeared in The Straits Times here.