Dr Wong Sweet Fun’s Redesigned Healthcare Ecosystem for Seniors Drives Better Long-term Outcomes

She’s described (in a good way) as the Chief Mischief of Khoo Teck Puat Hospital and Yishun Health. Turning traditional medical care on its head, Dr Wong Sweet Fun has dedicated her career to discovering more resonant ways to enhance health for Singapore’s seniors. Although she was not trained as a designer, she has harnessed a systemic outlook and design research methods, and led the way to the Communities of Care framework that reflects the national agenda for preventative health.

Article by Narelle Yabuka.

What drives you to tread the path you do in life? In the case of Dr Wong Sweet Fun, a Senior Consultant of Geriatric Medicine at Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH), professional and personal drivers have always been interlinked, and powerfully so.

Dr Wong had dreamed of becoming a doctor since childhood. In a family with five children of similar ages, she realised however that the hard study involved would have to be underpinned by self-sourced financing. “We were all ready to go to university around the same time,” she recalls, “but we weren’t a rich family, and I knew medical school was going to be costly.”

She journeyed from Malaysia to Singapore in 1979 on an ASEAN scholarship to read her A levels, and subsequently secured a Local Merit Scholarship from the Singapore Public Service Commission to study medicine at the National University of Singapore. After completing her post-graduate exams in 1991, she chose to specialise in geriatrics and joined the ranks of Tan Tok Seng Hospital’s new Department of Geriatric Medicine.

I remember thinking that were it not for the generosity of the Singapore wage earner paying taxes to finance my studies, I would not have been where I was. These people would have aged further by the time I finished my training to be a geriatrician. How could I turn my back on them? Geriatric medicine was a way for me to give back to Singapore, through its people and government, who had given me earlier opportunities.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

This marked the start of a professional journey driven by an impactful combination of inquisitiveness, empathy, and big-picture thinking, which would come to reshape the nation’s approach to healthcare for seniors and positively impact the lives of thousands.

Changing the prescription

“People were coming in too late,” says Dr Wong, reflecting on her many years of treating full-blown, catastrophic illnesses at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, then at Alexandra Hospital, and from 2010, at the newly opened KTPH (part of the Yishun Health network). “As a geriatrician, I saw sick older persons brought in by their families and felt that I could do so little for them,” she recalls regretfully.

Singapore has been ageing rapidly. Back in 1991, when Dr Wong entered the field of geriatric medicine, Singaporeans 65 years and above constituted around 6 per cent of the citizen population. The figure soared to 19 per cent in 2023 and projections indicate that by 2030, 24.1 per cent of citizens will be 65 years and above.

Unfortunately, the increased longevity has occurred in tandem with a massive uptick in the prevalence of chronic diseases – often related to lifestyle choices and tending to go undiagnosed until complications arise.

A declining birth rate has contributed to the demographic shift, but so too has Singapore’s success in providing the conditions to support longevity. “Singapore has performed well in our nation building – of infrastructures, economy, education, security, and medical care provision,” says Dr Wong, “leading to the possibility of longer lives.”

Being recognised as the world’s sixth Blue Zone is “a great achievement,” she says, “but it will be better if the extended years are also spent in good health.”

To avoid illness or injury and maintain health, we need more than healthcare workers. We need good teachers, engineers, architects, builders, cleaners, rubbish collectors, politicians, and administrators. In fact, we need everyone to be responsible, especially with their life habits.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

It was clear to Dr Wong that if Singapore was to avoid a situation of mass long-term institutionalised care for a large population of chronically ill older people, there needed to be an upstream intervention. People had to be encouraged to adopt and maintain healthier lifestyles.

Beyond traditional medical care, there are many other determinants of health – factors such as physical activity, diet, social interaction, and mental and emotional wellbeing. The question vexing Dr Wong was, how could these be integrated more holistically with healthcare when every industry or ministry had to stick to its core business? She recalls, “Some people would ask, for example, ‘Why is a doctor looking at social issues?’ Other would say, ‘Go ahead if it brings health benefits.’” Dr Wong was undeterred.

I asked myself, ‘Should we intervene?’ Maybe it was the weird streak in me, but from where I stood, the answer was, ‘Challenge accepted!’ It felt like it should be done.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

So, from around the year 2000, she embarked on a process of venturing out beyond the hospital walls to engage people in health-related activities in their own communities. The initiatives she pioneered were designed to be interactive and to enable the development of meaningful relationships between healthcare workers and the communities they serve.

Dr Wong was out there with her team, joining exercise classes and striking up conversations about healthy eating. “We would hear what was behind people’s choices,” she says. “It was very interesting. We didn’t learn any of this in medical school.” Her hands-on approach set her on a trajectory of many years of what she calls “accidental innovation”.

The original purpose was to get Singaporeans out of their habit of being recurrent ‘goodie bag collectors’. In the past, people would just come to a health promotion session, sit down, listen, collect a goodie bag, and go home unchanged. We said, ‘No more of that. You need to be able to make some changes. You’re going to be hands on and active.’

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

Uncovering design’s role in systems

Dr Wong’s move to KTPH – the recipient of a President*s Design Award (P*DA) in 2011 for its creation of a nature-laden healing environment rather than a clinical box – was an opportunity to test some behavioural insights and more formally explore a systemic approach to the creation of health.

She was involved in the design of the hospital as a future user of the building, sharing insights about healthcare work with the architects and planners. “It was quite novel to me that the hospital planner would ask the staff how they want their working space to be,” Dr Wong recalls.

She took the interactive spirit on board and raised some eyebrows by inviting her patients to provide their input on how to improve their experience, too. Unwittingly, perhaps, she was adopting a core pillar of the design thinking process, by seeking a better understanding of the perspective of hospital users.

KTPH was designed to invite the community in – to make people feel welcome to explore its gardens. A health-promoting park was developed alongside at Yishun Pond (formerly an unloved stormwater repository) with “stealth health” features such as stationary bicycles that pump pond water into the air, and hopscotch markings on a running track around the pond. “Ta-daa! We had introduced cheap high-intensity interval training into people’s exercise regimes,” says Dr Wong.

Her input extended to working with nurses, therapists, and a design consultant on the creation of crockery for inpatients that would improve the experience of eating from a hospital bed. For Dr Wong, the whole experience of creating KTPH as a nurturing, inclusive community place was transformative. “It was a process of changing our lenses as health professionals,” she recalls.

I came to the conclusion that design is actually the first step in any system-building effort. Without it, we will need to pay recurrent operational costs and exert effort to work around inefficiencies. We really need to put design up front.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

A turning point

Eventually, buoyed by staff (such as Dr Wong) with strong aspirations to change things for the better, the hospital recognised the value of bringing designers into its fold. “We put a culture of design in the hospital,” recalls Dr Wong.

“We were the first hospital in Singapore to actually employ designers as our staff. What they showed me was reframing,” she adds – the capacity to look past cosmetic quick-fixes and find solutions that really address people’s unarticulated needs. In short, thinking about the bigger picture and asking different questions will lead you to different answers.

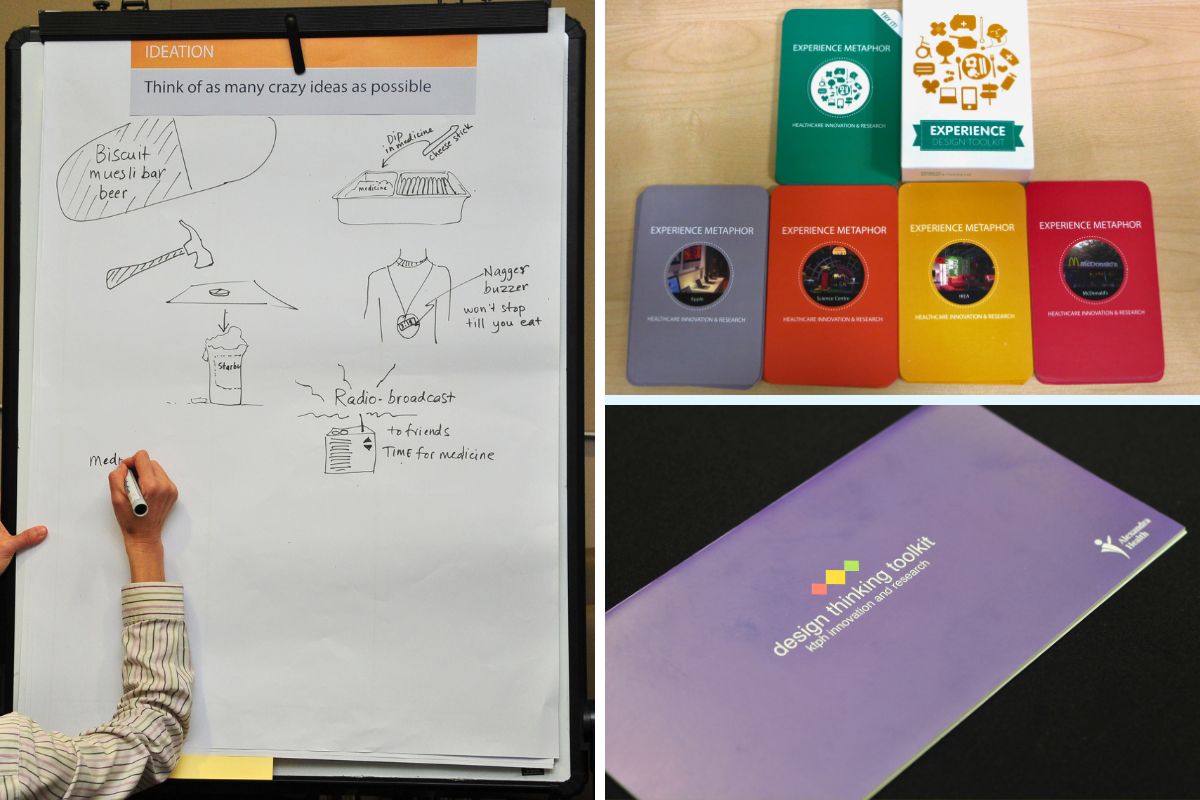

Design workshops for staff, design tools (such as behaviour insight cards for brainstorming), design conferences, and a rapid prototyping fund were developed. “We worked on wicked issues in the hospital,” says Dr Wong, “the biggest of which is always waiting time. We also dabbled with some design research to understand more about what people were really looking for.”

I didn’t (and still don’t) have any credentials or training in design, design thinking, or innovation. I was just solving problems. But people started saying, ‘That’s innovative.’ I didn’t start any project thinking, ‘I will do something innovative.’ So, I must have accidentally innovated.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

The value of thinking differently

With KTPH up and running, Dr Wong was observing a high number of older patients being re-admitted within short periods of time. As opposed to the response of simply adding more beds, she tried to think differently about the problem with her new Design Research and Innovation team. Why were so many people coming in, and coming back? Was there a bigger answer waiting to be found out in the neighbourhoods?

Their first major piece of design research work resulted in the lauded Ageing-in-Place programme, which received a United Nations Public Service Award in 2014. It contained two components: making healthcare more visible in neighbourhoods with community nurse stations; and visiting people’s homes to understand how social, behavioural, and environmental factors were impacting health.

The community nurses built trusting relationships with seniors in their homes – which for many patients, would have been an entirely new way of interacting with the healthcare system.

If you build a connection and share a common language, then you can say you are truly empathetic.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

Dr Wong’s earlier work on active, participatory health programmes had encouraged a sense of agency in people for determining their health. Ageing-in-Place developed an approach of supported self-management. The safety net of the hospital was there if needed, but residents were no longer to think of themselves as passive recipients of care.

I’m not the first one to do this, but I’d say I’m the stubborn one. I just felt like this really needed to continue. Based on what people have told me, I’m Chief Mischief – that’s my new title!

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

Ageing-in-Place was followed by another pivotal programme: an ethnographic study titled Project Orange. It was named after the gift of oranges that Dr Wong and her team used as the basis for starting conversations with people. The purpose was to decipher what contributes to older people maintaining wellness.

They walked the ground in Yishun, talking to residents about their needs, interests, and visions of what makes a good life in their senior years. They found that participation in communities held great benefit; it fostered trust-based social networks and a sense of belonging, with exchanges of experiences and skills bringing both improvement and meaning to life.

For Dr Wong, this spelled an immense opportunity. “Encouragement from your community normalises healthier choices,” she explains, “and makes it easier and more comfortable to build such changes into your lifelong routine.”

“We also started seeing people’s strengths,” she adds. “Working with people’s strengths was much better than working from where they were as defined by their illness,” she says. Individuals can build on their strengths in an effort to be and keep well, she recognised, and furthermore, every person offers value to those around them.

We were surprised by how neighbours wanted to contribute to each other’s benefit. It gives people fulfilment to be seen as valuable members of their community.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

Creating health with Communities of Care

Ultimately, Project Orange led to the development of Yishun Health’s Communities of Care framework, and the co-creation – with residents – of community nodes, where residents can mobilise one another to build the very communities they want. Currently, there are 39 community nodes in the Yishun Health catchment area, and another 12 exist outside that zone. In Yishun alone, nearly 8,000 residents have been reached through Communities of Care initiatives.

The nodes, which include community nurse stations and Wellness Kampung spaces in public housing void decks, are what Dr Wong calls “bumping spaces” within the ecosystem of care. They are places where residents can pop in to speak to a nurse, have kopi (coffee) with friends, share a pot of healthy soup, attend an exercise session, borrow a book, or participate in resident-initiated, resident-led activities such as games, singing, and gardening.

Such activities, recognised by Minister for Health Mr Ong Ye Kung in 2022 after a visit to the Wellness Kampung in Yishun, are “important non-clinical interventions for healthy longevity”. Best of all – and despite the pandemic – of the 78 community programmes that have been launched since 2014, there are 62 still running as of March 2024. Two of the initiatives (Wellness Kampung and Share-a-Pot) have won international awards.

Certainly, design and design thinking within Khoo Teck Puat Hospital contributed to the systemic approach we took for our Communities of Care framework.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

By changing how she looked at problems, asking different questions, and finding different answers, Dr Wong and her team made, she says, “little stumbles into what we call person-centric design” over years of exploration and discovery. Their powerful realisation was that the traditional model of care needed reframing; the healthcare expert needed to broaden their perspective and embrace the more complex reality that the patient is also an expert on their own wellbeing.

It’s an ecosystem, but it’s not a controlled ecosystem. We are part of it, but we don’t control it. We watch it and go with it.

— Dr Wong Sweet Fun

Dr Wong’s non-linear, systemic approach is continuing to resonate internationally. Last year, for instance, the Head of the British Royal Medical Household, Dr Michael Dixon, visited the Wellness Kampung at Yishun. He recognised the game-changing effect of engaging residents in a health-creating community. The generalisation of this model, he said, could have a “huge impact on the health system at a relatively small cost.” He also praised the strong leadership of Dr Wong.

Now in her 60s, Dr Wong is aware that she will soon be handing the baton to a new generation of leaders. Her aspiration is that the ecosystem of community care and health creation will become a more intelligent one – with seniors who instinctively know how to use healthcare appropriately, and a healthcare system that knows just when to intervene.

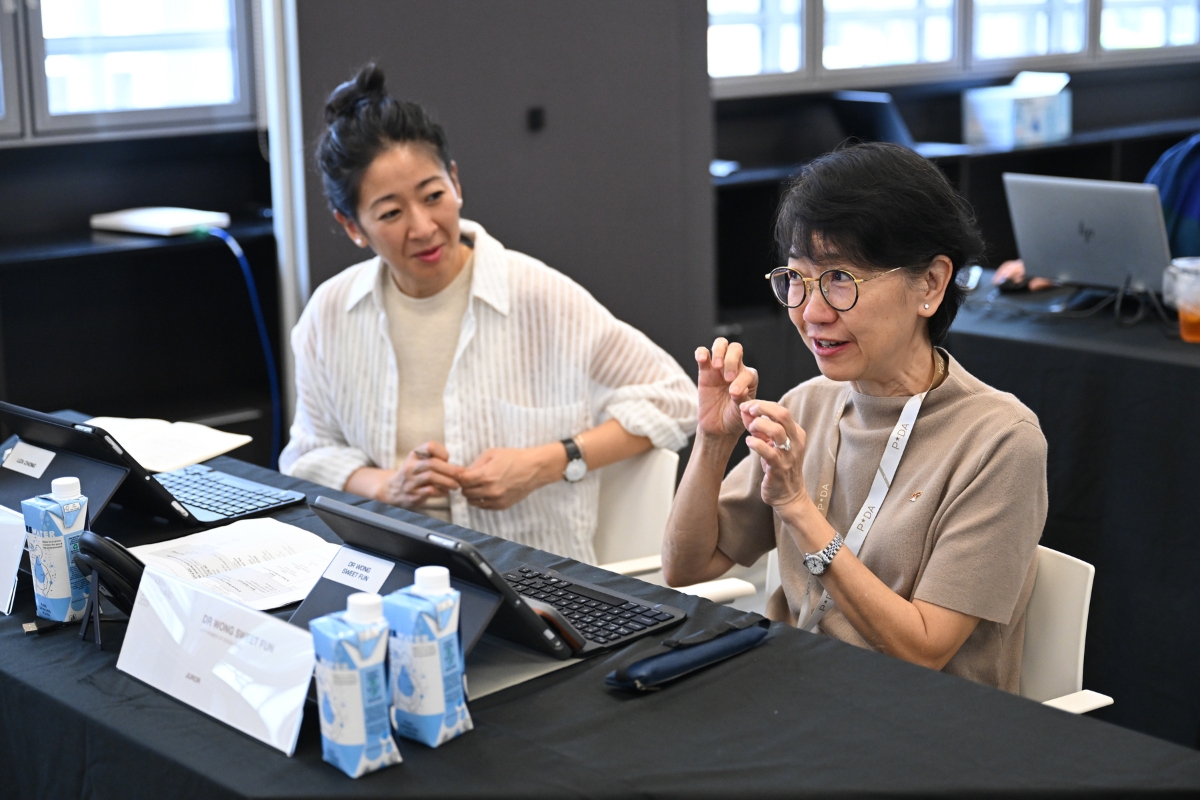

In the meantime, she has continued to develop her design muscles by serving as a Juror on the Design Panel of the 2023 cycle of the P*DA – bolstering the growing awareness within the design industry that a diversity of considerations are critical to achieving positive impact.

For Singapore Design Week 2024, she is working alongside P*DA 2023 recipient and designer Hans Tan on a new edition of his awarded project R for Repair, which will explore the creative repair of broken objects as a means of enabling difficult conversations. It promises to be a powerful expansion of design’s role well beyond a discipline-defined service.

In design, as in healthcare, the potential to change the game for the better is rich and ready to be explored by anyone with the drive to look through different lenses.