Deep research to create responsive communities

With the support of the Good Design Research initiative, social innovation consultancy Common Ground embedded design researchers in Jurong for six months to discover how residents and organisations think, behave and learn.

Research can give designers insights and ideas to develop unique products and services that stand out in a crowded marketplace. But deep research and experimentation is costly and time-consuming – and clients are often unwilling to pay for it until they first see some proof of value.

The Good Design Research (GDR) initiative was introduced in March 2020 to help designers achieve that proof of value so that they can convince clients or collaborators to support impactful and innovative work.

In the pilot run of GDR, seven projects, out of 60 eligible submissions, were selected by an evaluation panel to undertake research and work towards delivering “proof of concept” for their work in 12 months.

In this article, we look at the deep research component of an ongoing GDR project by Common Ground, a social innovation consultancy.

Image credit: Bold at Work

The secret to adaptive, resilient communities?

In 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak threw the global economy into a tailspin, triggered health fears and heightened tensions in communities as inequality and social division worsened.

This provided the impetus for Common Ground to ask if communities should always rely on government intervention in times of crisis. Or could a community be designed to be adaptive and resilient so it can learn to build structures and networks that respond to emergent needs, opportunities and threats?

Common Ground found partners who were also keen to investigate if communities could self-mobilise and take charge of their own interests, including their health. Together, they chose to work on a prototype community in Jurong, a district in western Singapore.

Common Ground had talked to residents, who mentioned that there were many activities in Yuhua (a part of Jurong) – describing it as “busy” and “happening”. Most of them, however, were organised by social service agencies and grassroots organisations. Furthermore, residents did not appear to have much motivation to rally themselves or have ownership over the existing programmes.

Could interventions work?

To find out, Common Ground first set out to uncover human systems that “make” a place and to discover what it will take to shift and sustain the culture of a place so that it becomes adaptive and responsive.

Embedding in the community

For the first phase of the project, which started in July 2020, Common Ground’s community researchers spent six months embedded in Jurong to understand the site, stakeholders, and context through ethnographic research.

They conducted interviews aimed at discovering:

- The community’s resources, assets and capitals

- Their needs and aspirations

- Resistances, i.e. the “unseen” or “unspoken” barriers to learning

- Opportunities to help community “see, act and learn” better to become more self-reliant and sustainable

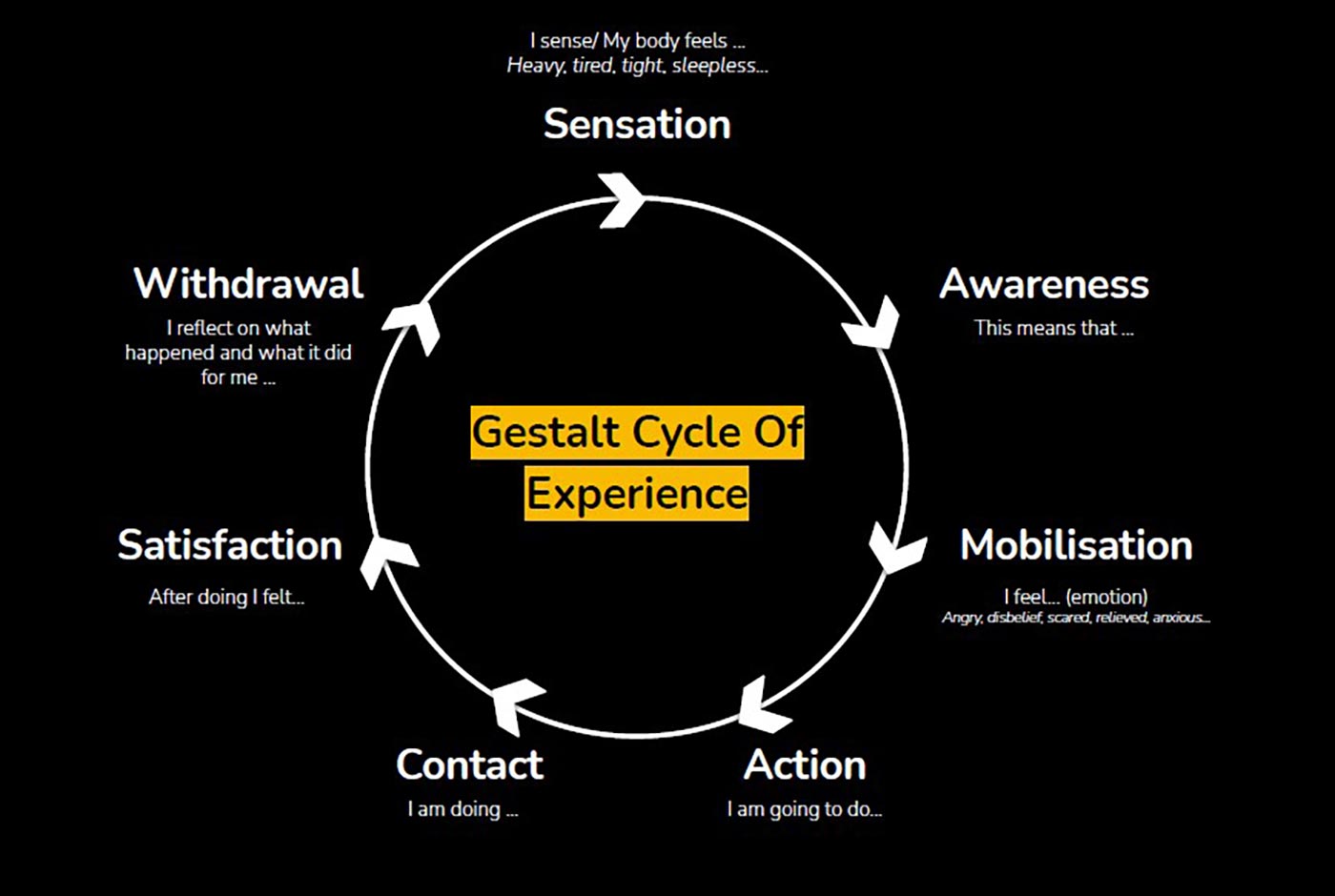

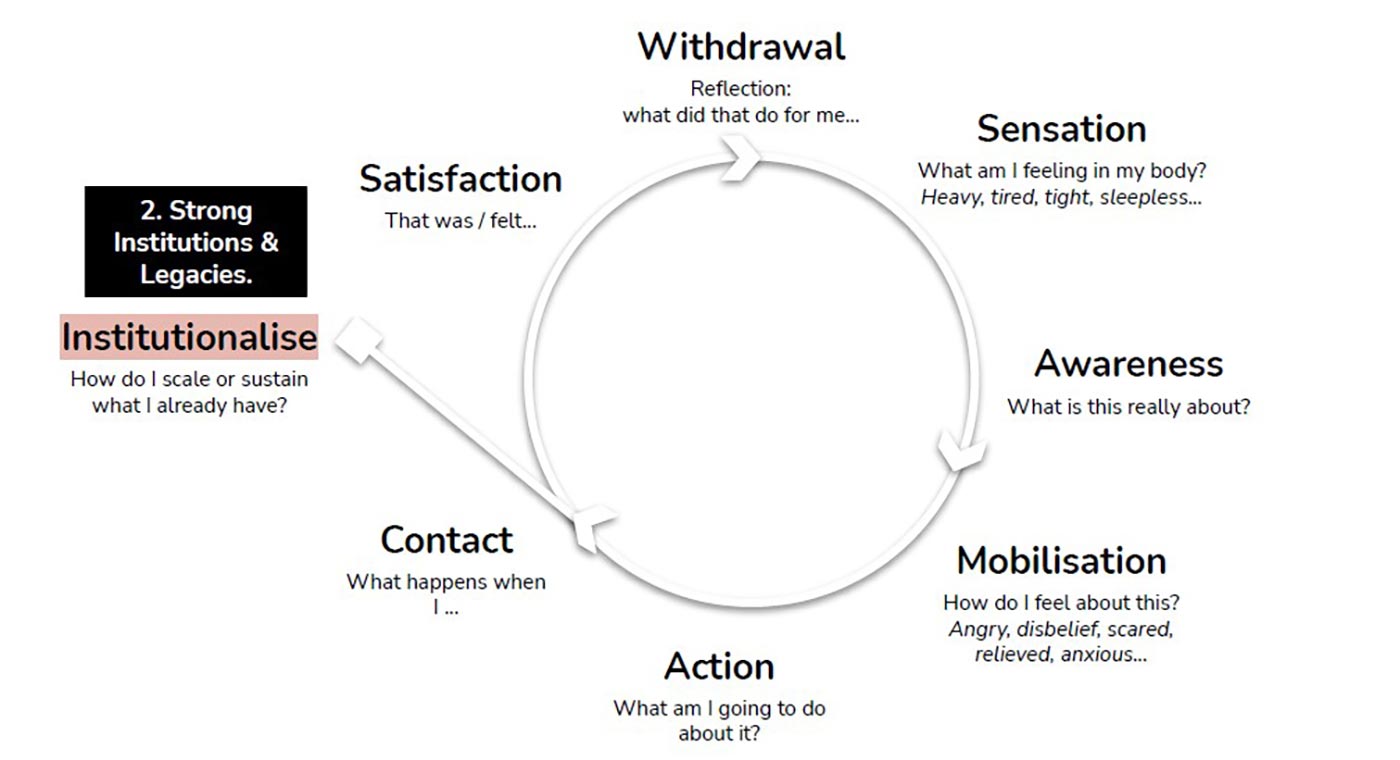

To this end, they used the Gestalt Cycle of Experience as a conceptual framework. (See figure below) This cycle is a basic map showing how a person becomes aware of a sensation, moves to respond (mobilisation, action and contact), and achieves satisfaction before reflecting on the experience (withdrawal).

The framework guided the team to understand and track an individual’s and community’s process of learning. They hoped to identify which stages of the cycle people were “stuck” at and from there suggest interventions to help them move past those barriers.

Over six months, Common Ground gathered qualitative data through “deep hanging out” – using observation, street intercepts, informal conversations and in-depth interviews – to draw out motivations and stories underlying behaviours.

Altogether, they intercepted 190 people on the streets; completed 29 in-depth one-on-one interviews with contacts; and interviewed seven organisations working in Jurong.

Teasing out qualitative data

To discover the community’s resources, assets and capitals, residents were asked questions such as “What do you love or are most proud of about Jurong?” during one-on-one interviews.

To assess what networks and communities mattered, researchers asked, “Is there someone in the community who is good at getting people to come together?” and “Who do you interact with on a regular basis?”

Image Credit: Bold at Work

Questions like “What do you think is stopping Jurong from being the place you want it to be?” or “Are there groups of people in Jurong you feel you cannot connect to?” aimed to tease out more data on barriers and boundaries.

Community partners and organisations operating in Jurong were asked different questions, such as “What do you see your role in the community as?” and “What do you think is missing or can be better in Jurong?”

Research findings

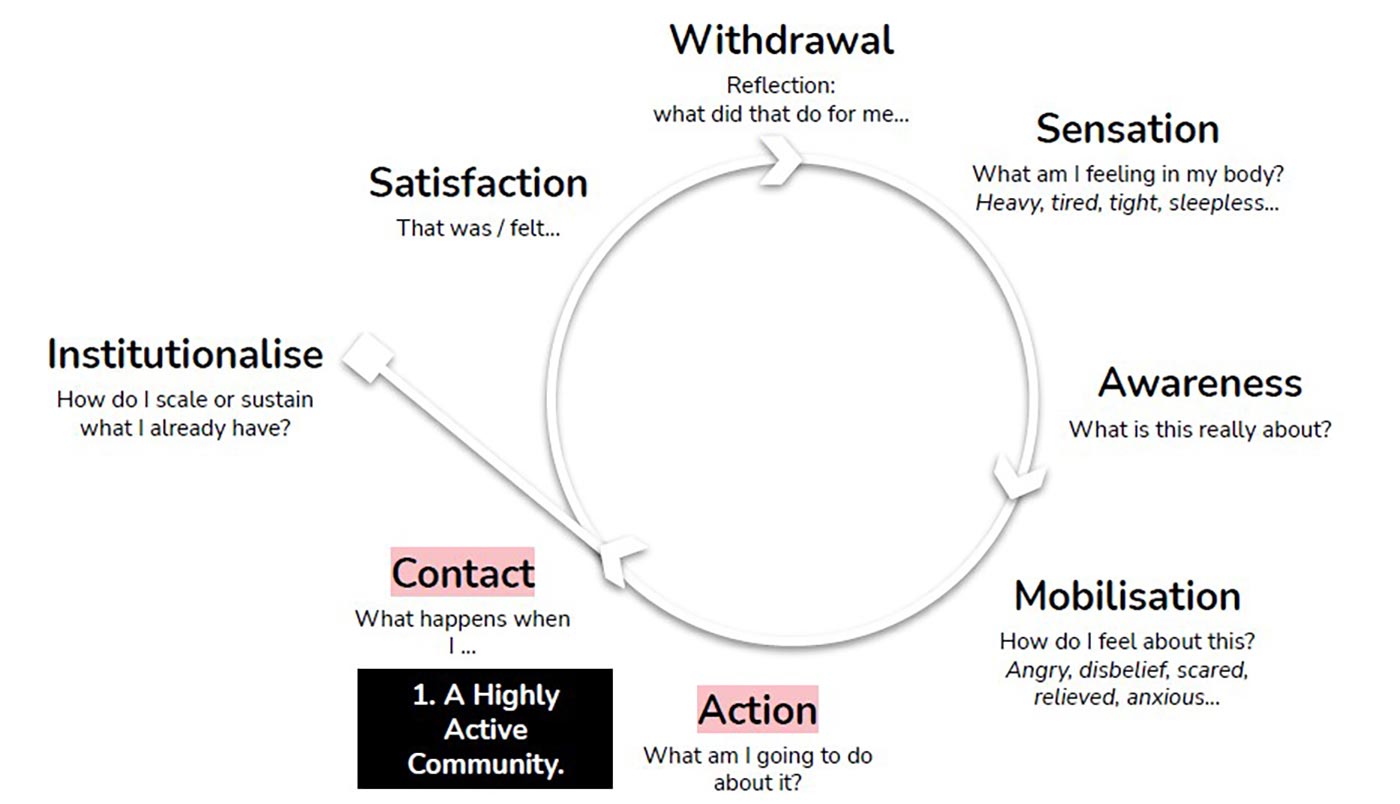

The qualitative data was synthesized and mapped onto the Gestalt Cycle to identify barriers to learning.

Highly Active Community

They found a strong grassroots presence and plenty of widespread and frequent community activities taking place across Jurong. On the Gestalt Cycle, the residents had no problems with the “action” and “contact” stages.

While most residents were aware of activities organised by the grassroots organisations, it was largely the senior citizens who participated. When programmes ceased due to high attrition rates or difficulty in sustaining engagement, new ground-up alternatives did not arise. This suggested that residents behaved as “consumers” who were willing only to act if/when the right programme arose.

Strong institutions and legacies

The researchers found a dominant presence of strong institutions in Jurong. While institutions facilitated scale and continuity in activities, relying on them resulted in a community that was “locked” into set habits of activities and programmes. This made it difficult to engage other residents outside the current networks, especially since the institutions were unconnected to one another and worked in silos.

They also observed the residents holding a narrative that change could only happen with “top-down” initiatives, highlighting a perception of low power among Jurong residents.

Therefore, the cycle (instead of being in a loop) goes off into a trajectory – with its reliance on institutions to keep things going in the community.

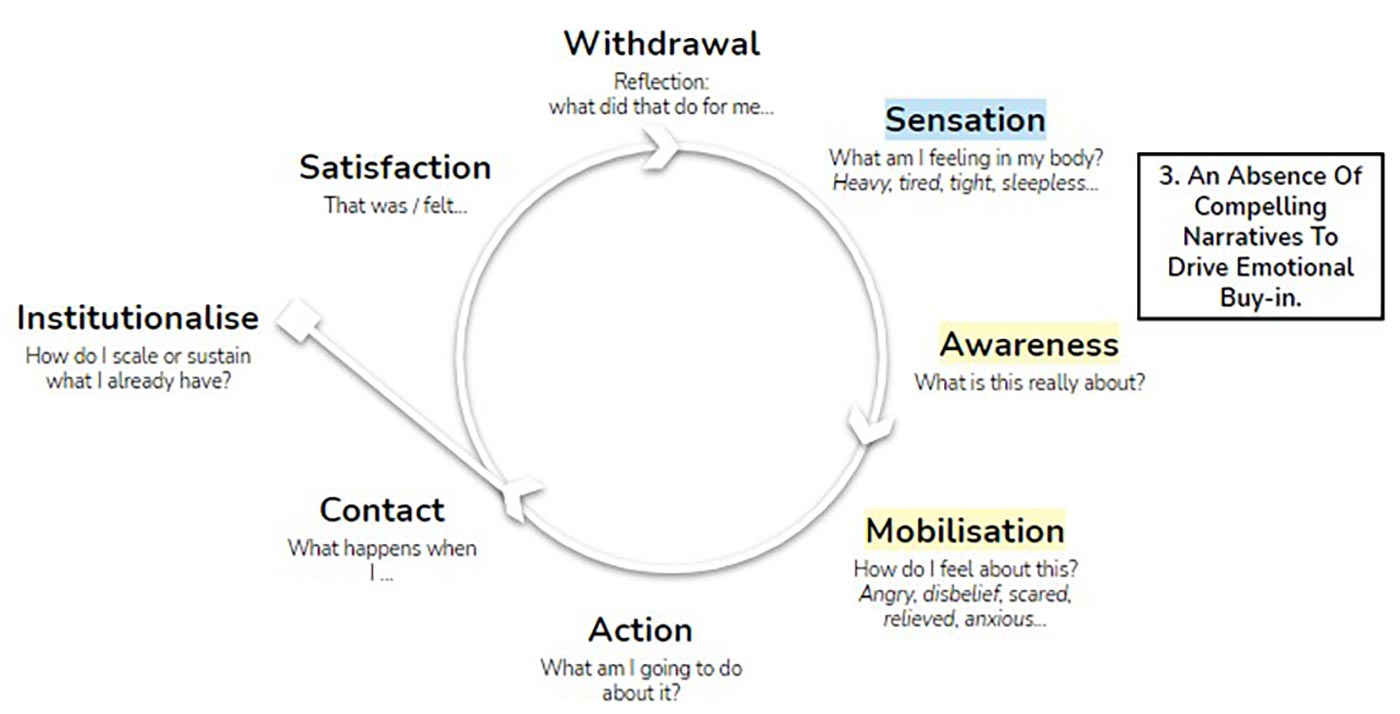

Absence of compelling narratives for emotional buy-in

The low level of ownership and personal agency observed in Jurong indicated that many residents were having difficulty mobilising into self-directed action. Many local organisations reported challenges recruiting and engaging volunteers, including handing ownership of programmes over to them. Interviews revealed that residents who were not engaged did not find the local organisations’ narratives for community and health initiatives relevant nor compelling enough for them to participate or to take ownership of.

Opportunities for intervention

From the findings, Common Ground identified several opportunities for intervention.

Key among them was to change the existing community narratives in order to help residents move past the stages they were “stuck” with i.e. the “sensation”, “awareness”, and “mobilisation” stages in the Gestalt Cycle.

This was based on Common Ground’s hypothesis that change starts with a story (narrative) as stories (narratives) reveal the underlying beliefs of individuals and communities, which in turn influence emotions.

Emotions then shape the individual or community’s decision to choose one course of action over another.

STORY > BELIEFS > EMOTIONS > ACTIONS

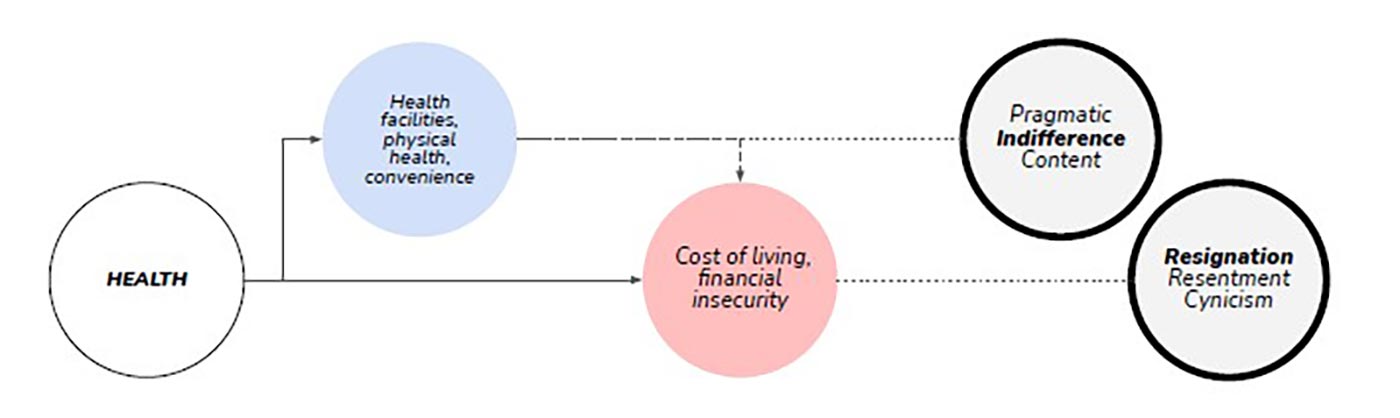

Common Ground thus set out to understand the prevailing stories the community had around the terms “health” and “community”.

For example, there were residents who would invariably talk about healthcare costs in Singapore and share about their financial insecurities when asked about the broad topic of health. This would trigger emotions of resignation, resentment, and cynicism.

As a result, the conversation shifted away from considering the individual’s health and life habits, to focusing on the seemingly impossible task of achieving health. This suggested that future health-promotion narratives should consider the community’s existing narratives on health in order to be effective in resonating with the community and mobilising people to take action.

Next steps after deep research

With their deep research done, Common Ground has moved into the next phase of “prototyping”.

“The GDR helped us to get a kickstart in the work we are doing that most consumers and markets don’t really understand yet. With a strong prototype to show, large stakeholders are going – yes that’s exactly what we are looking for!” said Tong Yee, Executive Director of Common Ground

With that, Common Ground will engage local organisations in Jurong along with their partner Bold At Work to develop new opportunities for intervention including creating new narratives, which will be tested on the ground.

Watch this space for further updates!