Beyond Sustainability, Dr Hossein Rezai Advocates a Regenerative World View for Built Environment Professionals

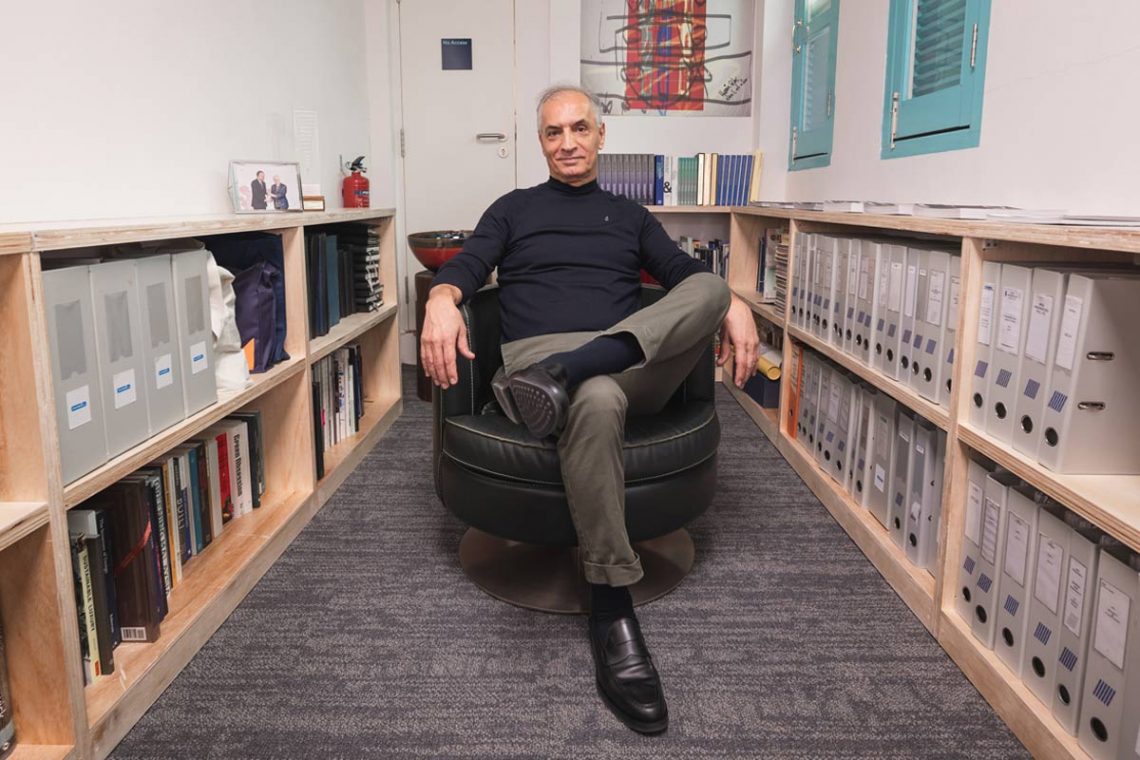

When structural engineer Dr Hossein Rezai received the ‘Designer of the Year’ accolade for the President*s Design Award in 2016, the Jury made note of his “holistic vision” and his “aspiration for engineering to achieve a higher purpose”. Now, in a global design role at Ramboll, he is using that same visionary spirit to chart a course for his colleagues in the climate crisis era. For Rezai, all roads lead to regenerative design.

Article by Narelle Yabuka.

In theory, and perhaps controversially, Dr Hossein Rezai wouldn’t really mind if machines took over. He has said as much in public forums. It’s not that he is utterly pessimistic. On the contrary, he is intensely hopeful that a better future is possible. He simply lacks confidence that a human-centric perspective will achieve it, given our poor track record of stewarding the planet to date.

“We always tend to fall back to this default mode of thinking that humans are good,” says the Singapore-based Global Design Director of engineering, architecture, and consultancy firm Ramboll, “but in reality, we have not done a good job with our patronage and the overwhelming power we have over everything, including nature.” He is doing his upmost, however, to reverse that tendency.

Given the catastrophic conditions we have created for climatic and planetary health, as well as the imbalance of power between members of our species and for species other than our own, the accomplished structural engineer believes change is overdue in how we think of ourselves and our role in natural systems. It follows, naturally, that he also advocates changes to how we design.

He is not alone. The last few years have witnessed a rapid expansion of dialogue globally about regenerative design – an approach rooted in systems thinking, aligned with natural systems, and targeting a mutually beneficial co-evolution between humans and nature. As opposed to simply ‘doing less harm’, which has been the remit of much sustainable design, regenerative design proposes positive contributions and the repair of damage that has already been done – that is to say, ‘doing more good’.

Regenerative design is not a subset of sustainability, which it has so far been seen as. It is not the case that the more sustainable you are, you suddenly become regenerative. There’s a huge gap to jump across.

— Hossein Rezai

Having led his own Singapore-headquartered civil, structural, and geotechnical engineering consultancy, Web Structures, since 1996, Rezai and his team (based in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Shanghai, and London), amalgamated with Ramboll in 2020.

Now, as a leader in an international firm of some 18,000 built and natural environment professionals in 35 countries, Rezai has an immense and rare opportunity to influence thinking at scale and shift the way thousands of projects are approached for the better.

He is seizing that potential energetically, with a mandate for regenerative design, systems thinking, and a vision of a more ecological civilisation. To achieve it, he is instituting practical tools that his colleagues at Ramboll can use for guidance on the journey toward a more regenerative future.

Everything, everywhere, all at once

“In tackling the challenge of regenerative design, it can feel like doing everything, everywhere, all at once,” admits Rezai. “I know that’s a movie title,” he continues, “but we need to be doing this because of the crisis that we are all in and the urgency that exists in dealing with the complex problems we have created. The trouble is, we have never learned how to deal with complex problems well.”

Typically, he describes, we have used reductive approaches – dividing complexity into manageable chunks that may not, when individually solved and aggregated, represent a meaningful solution to the original larger issue. A regenerative world view has the opposite effect of opening up the vision and ethos of design – creating more possibility for positive change precisely by embracing a raft of considerations in concert. Regenerative design requires a different way of thinking about how human endeavours interact with the natural world, and how professional disciplines can co-create rather than compromise.

So, while the sustainable design approach embodied terms and concepts such as conventional materials and fuels, single client centricity, and mono-species interests, a regenerative design approach favours new materials and composites, renewable energy, a multiplicity of clients, a systems and ecology-based approach, multi-species interests as well as those of the unborn, and a symbiotic relationship with other disciplines.

Regenerative design has a different starting point from traditional design. We need to learn that and start with those considerations.

— Hossein Rezai

Opportunities to do better

“One of the things I’ve been working on is developing a regenerative design ethos and directions so the 5,000 people at Ramboll who are in the buildings market, and the 13,000 who are in other markets – energy, environmental management, et cetera – can all have the same north star of regeneration with a common understanding,” explains Rezai. “Quite a lot of the ideas are very understandable. What we need is scale,” he adds.

A key method of building that common understanding is a new chart-based tool known internally as an ‘opportunity matrix’ for regenerative design. The matrix contains 16 drivers ranging from distinct components such as water, air, light, sound, soil, vegetation, biodiversity, waste, and carbon, to more complex considerations such as biomimicry, integrated connectivity, natural systems, massing and fragmentation, collaboration, social equity, and coexistence. It can be used to guide the assessment of a site’s existing degeneration and for developing ambitions and a road map to design a project with regenerative design outcomes.

“For every project, we rank the opportunities to do better in each driver area. Take water as an example. Whatever it is that you’re designing, whether it’s a house or data centre, you would ask: How is the water regime on this site going to be affected after I build this project, compared to before? Is it better or worse? Is there the opportunity to make it better by revising our design?” Rezai explains.

“We don’t yet have a project that is fully regenerative in every aspect,” he explains, “and maybe we will never have one because the outcome is dependant on the constraints and context of each project. But certainly, some attributes will be regenerative.”

Regenerative design ideas are as advanced across Asia as they are anywhere. In this region, there are a lot of beautiful developments with nature-based systems.

— Hossein Rezai

Developing a carbon budget

As part of his efforts to build a regenerative design lexicon and approach at Ramboll, Rezai is also instrumental in the firm’s efforts to bring to fruition a feasible cap figure for the embodied carbon footprint of its projects. “Our intent is to commit to developing designs and buildings with a ceiling on the embodied carbon – a number for the kilogrammes of embodied CO2 per square metre,” he explains.

“Quite a lot of people talk about reducing embodied carbon. They’ll say, ‘We’ll reduce it by 30% by 2025,’ or ‘By 2030, we’ll reduce it by 50% compared to a baseline of 2021.’ But nobody that I’m aware of has put a number on it,” he says. “So, amongst the major companies and consultancies, I think Ramboll will be the first to do so.” After 18 months of work, the firm is expected to announce its baseline figure soon.

“The ceiling cannot be one number across building types – commercial, residential, et cetera. There will also be different numbers for buildings that are, say, 10 storeys compared to 50 storeys high, or located in Taipei with typhoons or in Singapore with mild winds,” explains Rezai. Thus, from a baseline figure, the cap will be calculated according to the type of project, its scale, its location, and so on.

Rezai, ever a champion of progress, is clearly proud of and energised by this Ramboll initiative, as well as excited by the prospect of reducing the baseline figure over the decades to come. He mindfully points out, however, the need for thinking systemically about it. “Within the building industry,” he says, “we cannot reduce the embodied carbon footprint to zero by ourselves. We need the energy industry to help. As the embodied carbon of energy comes down, the embodied carbon of the materials we’re using will come down. As the energy industry helps us, we need to help them in return by developing new materials, new techniques, and bio-based alternatives.”

A journey toward alignment and cross-pollination

Such is the pathway to regenerative design – in part, a sustained effort of co-creation, or at least, a recognition of the rich potential for better outcomes within aligned approaches. Crossing the disciplinary threshold may run against the grain of established professional silos, but competencies are already evolving, says Rezai, who observed as much in his role as Design Panel Chair of the President*s Design Award (P*DA) Jury in 2023.

“One of the things that really encouraged me throughout the P*DA 2023 adjudication was the interdisciplinary nature of the candidates and projects,” says Rezai. He continues, “In the Design Panel, we could have awarded a project or candidate under several different categories. It’s not that people are becoming Jacks of many trades and master of none; they are actually becoming master of three or four.”

In years gone by, we specialised in one topic. If we undertook a PhD, we would study a very focused and narrow topic. But today, with our machine friends to help us, we can be more ambitious. We can become a master of several topics.

— Hossein Rezai

The diverse composition of the P*DA Jury’s Design Panel, in Rezai’s view, has been an ideal complement to that multiplicity of practice. In 2023, the Design Panel Jury contained individuals working in the fields of care, industrial design, digital technology, health, graphic design, landscape architecture, inclusive design, architecture, strategic and experience design, and environmental gerontology. “Design is so multidimensional,” says Rezai, “and every discipline has its blind spots. As we move further toward regeneration, I believe every design jury should include an anthropologist and biologist as well.”

Although he rarely heard the word “regenerative” being used by P*DA 2023 candidates during their presentations, Rezai observed many examples of regenerative principles. “The project attributes the candidates were describing were regenerative attributes. I think the idea of integrating with nature in the context of Singapore has actually been ripe for some time,” he says – a strong basis from which to build ambition for regenerative design outcomes.

What would help us get there, he suggests, is to deepen our understanding of nature. “If you don’t understand nature, how can you be in tune with it?” he asks. “We need to dehumanise our processes rather than trying to make everything and everybody else behave like humans. We should actually try to remove some of the things we have introduced into systems and naturalise them.”

Read our unfolding series of stories on creative discovery and making life in Singapore ‘Better by Design’.