A Playbook for Building a Design-Led Culture

What is Culture?

Culture is the bedrock of an organisation. Various studies have shown that an organisation’s culture has a direct impact on the work it does. Organisational culture determines how individuals go about their daily work, and can dictate how an organisation performs in relation to its strategy. Yet culture can take many forms, differing according to the goals of each organisation.

For design-led organisations, design is embedded so deeply that it becomes more than just part of their processes and strategy, but a part of their culture. To gain a meaningful and deeper understanding of how design-led culture allows organisations to strive for better, a qualitative year-long study commissioned by the DesignSingapore Council was conducted by ROHEI Learning & Consulting with senior management personnel from 27 leading organisations with strategic presence in Singapore. These organisations include family-run small and medium-sized enterprises, large local enterprises, multi-national corporations, and government agencies.

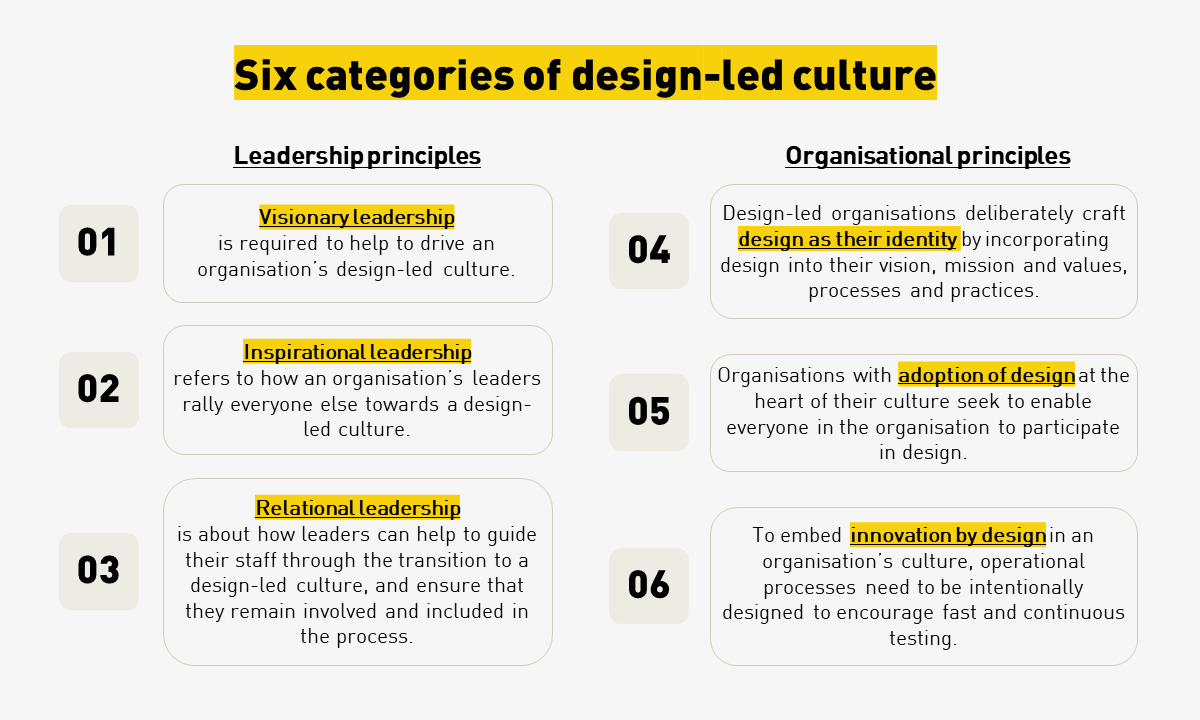

The findings from the study culminated in a playbook which presents “22 Principles for Building a Design-Led Culture”, grouped into six broad categories (see image below). The playbook contains various case studies and examples from the 27 organisations that illustrate how they have successfully implemented design at the leadership and organisational level.

Embark on your own journey to build a design-led culture

Organisations (regardless of industry or size) that are looking to embark on their very own journey towards building design-led cultures can:

- Leverage the Design-Led Culture Survey which is featured in the playbook, for a quick litmus test on how their employees perceive their organisation’s current culture in relation to design. This can be used as a starting point to identify areas of strength as well as areas to focus on.

- Refer to the recommendations associated with each of the 22 principles that employees can put into practical action, based on their roles in the organisation.